Sickle cell anemia, a hereditary hemoglobin disorder, presents a myriad of physical and psychosocial challenges for individuals living with this condition. As nurses, our commitment to patient advocacy and holistic care makes us indispensable in supporting patients with sickle cell anemia throughout their journey.

This article aims to provide a nursing perspective on sickle cell anemia, offering insights into the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and evidence-based interventions to optimize patient outcomes. By deepening our understanding of this complex condition, we can better empower ourselves to deliver compassionate care and foster positive changes in the lives of those affected.

Table of Contents

- What is Sickle Cell Anemia?

- Pathophysiology

- Causes

- Clinical Manifestations

- Complications

- Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

- Medical Management

- Nursing Management

- See Also

What is Sickle Cell Anemia?

Sickle cell anemia is an inherited form of hemolytic anemia.

- Sickle cell anemia is a severe hemolytic anemia that results from inheritance of the sickle hemoglobin gene.

- The sickle hemoglobin (HbS) gene is inherited in people of African descent and to a lesser extent in people from the Middle East, the Mediterranean area, and the aboriginal tribes in India.

- Sickle cell anemia is the most severe form of sickle cell disease.

Pathophysiology

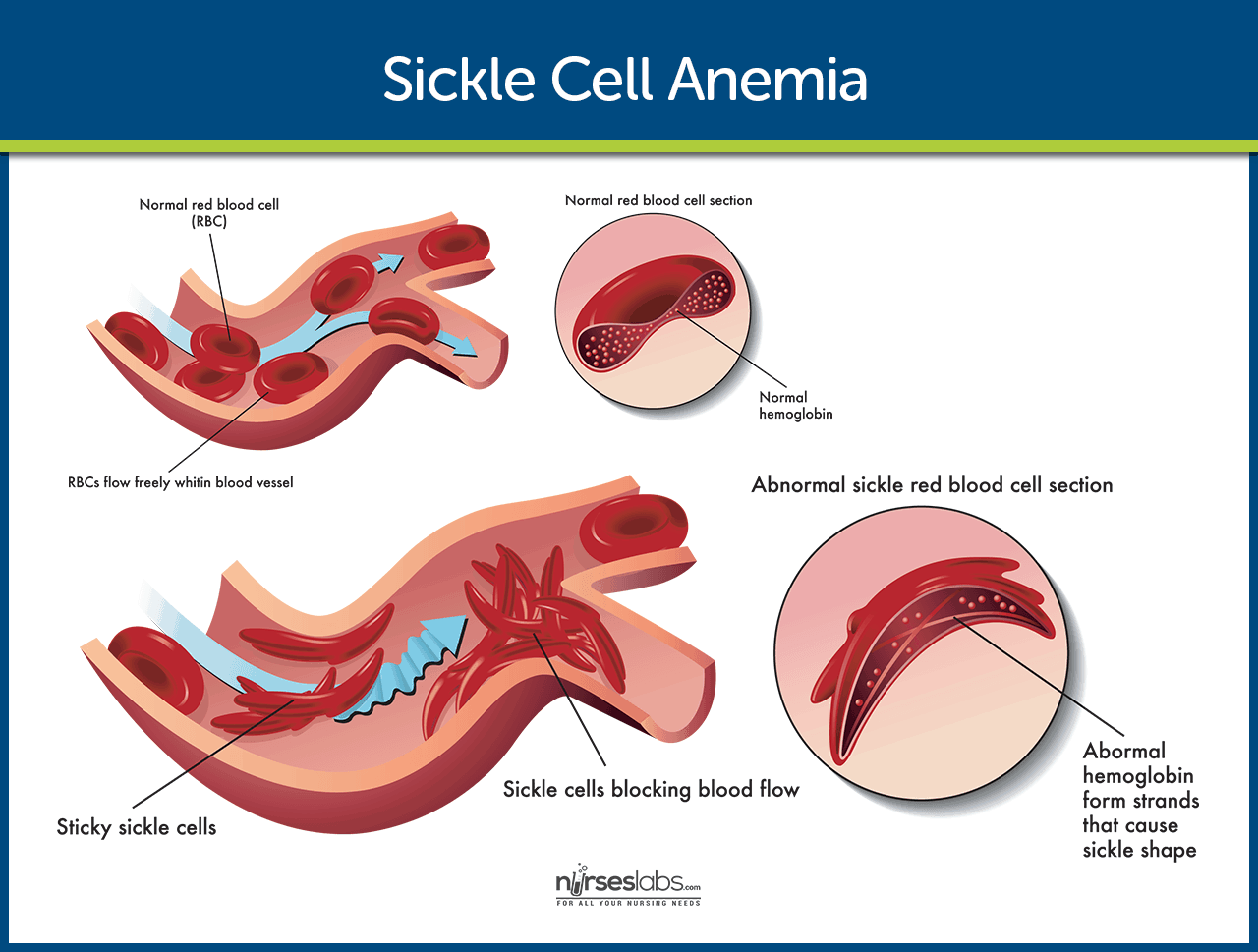

The HbS gene causes the hemoglobin molecule to be defective.

- Exposure. The sickle hemoglobin acquires a crystal-like formation when exposed to low oxygen tension.

- Change in the shape. The oxygen level in venous blood can be low enough to cause the erythrocyte to lose its round, pliable, biconcave disk shape.

- Adherence. These long, rigid erythrocytes can adhere to the endothelium of small vessels; when they adhere to each other, blood flow to a region or organ is reduced.

- Reversion. If the erythrocyte is again exposed to adequate amounts of oxygen before the membrane becomes too rigid, it can revert to normal shape.

Causes

The causes of sickle cell anemia include:

- Cold temperature. Cold can aggravate the sickling process, because vasoconstriction slows the blood flow.

- Tissue hypoxia. Tissue hypoxia and necrosis causes a type of sickle cell crisis called the sickle crisis.

- Human parvovirus. Aplastic crisis results from infection with the human parvovirus.

- Splenic infarction. Sequestration crisis results when other organs pool the sickled cells, just like the spleen.

Clinical Manifestations

Symptoms of sickle cell anemia vary and are only somewhat based on the amount of HbS.

- Anemia. Anemia is always present; usually, hemoglobin values are 7 to 10g/dl.

- Jaundice. Jaundice is characteristic and usually obvious in the sclerae.

- Dysrhythmias. Dysrhythmias and heart failure may occur in adults.

- Enlargement of the bones. The bone marrow expands in childhood in a compensatory effort to offset anemia, sometimes leading to enlargement of the bones of the face and skull.

Complications

Complications of sickle cell anemia include:

- Infection. Patients with sickle cell anemia are unusually susceptible to infection, particularly pneumonia and osteomyelitis.

- Stroke. Due to the decrease in oxygen supply because of the sickling, stroke may occur.

- Renal failure. Blood flow is reduced to other body tissues including the kidneys, which may lead to renal failure.

- Heart failure. The heart compensates for the decreased blood distribution by pumping more blood, and it may ultimately fail if it wears out.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

The patient with sickle cell anemia usually has the following laboratory results:

- CBC: Reticulocytosis (count may vary from 30%–50%); leukocytosis (especially in vaso-occlusive crisis), with counts over 20,000 indicate infection, decreased Hb (5–10 g/dL) and total RBCs, elevated platelets, and a normal to elevated MCV.

- Stained RBC examination: Demonstrates partially or completely sickled, crescent-shaped cells; anisocytosis; poikilocytosis; polychromasia; target cells; Howell-Jolly bodies; basophilic stippling; occasional nucleated RBCs (normoblasts).

- Sickle-turbidity tube test (Sickledex): Routine screening test that determines the presence of hemoglobin S (HbS) but does not differentiate between sickle cell anemia and trait.

- Hemoglobin electrophoresis: Identifies any abnormal hemoglobin types and differentiates between sickle cell trait and sickle cell anemia. Results may be inaccurate if patient has received a blood transfusion within 3–4 mo before testing.

- ESR: Elevated.

- Erythrocyte fragility: Decreased (osmotic fragility or RBC fragility); RBC survival time decreased (accelerated breakdown).

- ABGs: May reflect decreased Po2 (defects in gas exchange at the alveolar capillary level); acidosis (hypoxemia and acidic states in vaso-occlusive crisis).

- Serum bilirubin (total and indirect): Elevated (increased RBC hemolysis).

- Acid phosphatase (ACP): Elevated (release of erythrocytic ACP into the serum).

- Alkaline phosphatase: Elevated during vaso-occlusive crisis (bone and liver damage).

- LDH: Elevated (RBC hemolysis)

- Serum potassium and uric acid: Elevated during vaso-occlusive crisis (RBC hemolysis).

- Serum iron: May be elevated or normal (increased iron absorption due to excessive RBC destruction).

- Total iron-binding capacity (TIBC): Normal or decreased.

- Urine/fecal urobilinogen: Increased (more sensitive indicators of RBC destruction than serum levels).

- Intravenous pyelogram (IVP): May be done to evaluate kidney damage.

- Bone radiographs: May demonstrate skeletal changes, e.g., osteoporosis, osteosclerosis, osteomyelitis, or avascular necrosis.

- X-rays: May indicate bone thinning, osteoporosis.

Medical Management

Treatment for sickle cell anemia is the focus of continued research.

- Peripheral blood stem cell transplant. This may cure sickle cell anemia, however, this is only available to a small subset of affected patients, because of either the lack of a compatible donor or because severe organ damage is a contraindication.

- Transfusion therapy. Chronic RBC transfusion therapy may be effective in preventing or managing complications from sickle cell anemia.

- Supportive therapy. Adequate hydration is important during a painful sickling episode; aspirin is very useful in diminishing mild to moderate pain; NSAIDs are useful for moderate pain or in combination with opioid analgesics.

- Monitoring pulmonary function. Pulmonary function is monitored and pulmonary hypertension is treated early if found. Infections and acute chest syndrome, which predispose to crisis, are treated promptly. Incentive spirometry is performed to prevent pulmonary complications; bronchoscopy is done to identify source of pulmonary disease.

Pharmacologic Therapy

- Hydroxyurea has shown to be effective in increasing fetal hemoglobin levels in patients.

- Arginine has antisickling properties and enhances the availability of nitric oxide, the most potent vasodilator, resulting in decreased pulmonary artery pressure.

Nursing Management

Nursing management for a patient with sickle cell anemia focus on the following:

Nursing Assessment

Assessment data for a sickle cell anemia patient should include:

- Factors causing previous crisis. The patient is asked to identify factors that precipitated previous crisis and measures the patient uses to prevent and manage the crisis

- Pain levels. Pain levels should always be monitored using a pain intensity scale.

- Characteristics of pain. The quality, frequency, and factors that aggravate or alleviate the pain are included in the assessment.

- Infection. Because patients with sickle cell anemia are susceptible to infections, they are assessed for the presence of any infectious process.

Nursing Diagnosis

Based on the assessment data, major nursing diagnosis for the patient include:

- Acute pain related to tissue hypoxia due to agglutination of sickled cells within blood vessels.

- Risk for infection.

- Risk for powerlessness related to illness-induced helplessness.

- Deficient knowledge regarding sickle cell crisis prevention.

Nursing Care Planning and Goals

Main Article: 6 Sickle Cell Anemia Crisis Nursing Care Plans

The major goals for the patient are:

- Relief of pain.

- Decrease incidence of crisis.

- Enhance sense of self-esteem and power.

- Absence of complications.

Nursing Interventions

Nursing interventions for sickle cell anemia include:

Managing Pain

- Use patient’s subjective description of pain and pain rating on a pain scale to guide the use of analgesic agents.

- Support and elevate any joint that is acutely swollen until swelling diminishes.

- Teach patient relaxation techniques, breathing exercises, and distraction to ease pain.

- When acute painful episode has diminished, implement aggressive measures to preserve function (eg, physical therapy, whirlpool baths, and transcutaneous nerve stimulation).

Preventing and Managing Infection

- Monitor patient for signs and symptoms of infection.

- Initiate prescribed antibiotics promptly.

- Assess patient for signs of dehydration.

- Teach patient to take prescribed oral antibiotics at home, if indicated, emphasizing the need to complete the entire course of antibiotic therapy.

Promoting Coping Skills

- Enhance pain management to promote a therapeutic relationship based on mutual trust.

- Focus on patient’s strengths rather than deficits to enhance effective coping skills.

- Provide opportunities for patient to make decisions about daily care to increase feelings of control.

Increasing Knowledge

- Teach patient about situations that can precipitate a sickle cell crisis and steps to take to prevent or diminish such crises (eg, keep warm, maintain adequate hydration, avoid stressful situations).

- If hydroxyurea is prescribed for a woman of childbearing age, inform her that the drug can cause congenital harm to unborn children and advice about pregnancy prevention.

Monitoring and Managing Potential Complications

- Management measures for many of the potential complications are delineated in the previous sections; additional measures should be taken to address the following issues.

LEG ULCERS

- Protect the leg from trauma and contamination.

- Use scrupulous aseptic technique to prevent nosocomial infections.

- Refer to a wound–ostomy–continence nurse, which may facilitate healing and assist with prevention.

PRIAPISM LEADING TO IMPOTENCE

- Teach patient to empty the bladder at the onset of the attack, exercise, and take a warm bath.

- Inform patient to seek medical attention if an episode persists more than 3 hours.

CHRONIC PAIN AND SUBSTANCE ABUSE

- Emphasize the importance of complying with prescribed treatment plan.

- Promote trust with patient through adequate management of acute pain during episodes of crisis.

- Suggest to patient that receiving care from a single provider over time is much more beneficial than receiving care from rotating physicians and staff in an emergency department.

- When a crisis arises, emergency department staff should contact patient’s primary health care provider for optimal management.

- Promote continuity of care and establish written contracts with patient.

Promoting Home and Community Based Care

- Involve the patient and his or her family in teaching about the disease, treatment, assessment, and monitoring needed to detect complications. Also teach about vascular access device management and chelation therapy.

- Advise health care providers, patients, and families to communicate regularly.

- Provide guidelines regarding when to seek urgent care.

- Provide follow up care for patients with vascular access devices, if necessary.

Evaluation

Expected patient outcomes are:

- Relief of pain.

- Decreased incidence of crisis.

- Enhanced sense of self-esteem and power.

- Absence of complications.

Discharge and Home Care Guidelines

Education is always the best way to impart what the patient and the family need to know for home care.

- Vascular access management. Nurses in outpatient facilities or home care nurses may need to provide follow-up care for patients with vascular access devices.

- Communication. All health care providers who provide services to patients with sickle cell disease and their families need to communicate regularly with each other

Documentation Guidelines

The focus of documentation in a patient with sickle cell anemia include:

- Client’s description of response to pain.

- Acceptable level of pain.

- Prior medication use.

- Signs and symptoms pf infectious process.

- Plan of care.

- Teaching plan.

- Responses to interventions, teaching, and actions performed.

- Attainment or progress toward desired outcome.

- Long term needs.

See Also

Posts related to this care plan:

The genetic information on this page is weak and the wording incorrect. the content is not what is currently taught in the UK and in the sickle cell & thalassemia genetic risk assessment and counseling module at King’s College London.

So helpful thank you 😊

So helpful thank you

The page is well organized