Seizure disorders, commonly known as epilepsy, are neurological conditions that affect millions of individuals worldwide. Characterized by recurrent, unprovoked seizures, epilepsy can present in various forms, impacting people of all ages and backgrounds. As a significant neurological health concern, understanding the complexities of seizure disorders is crucial for healthcare professionals, patients, and their families.

This article aims to provide a comprehensive overview of seizure disorders, delving into their etiology, classification, diagnosis, and management strategies.

Table of Contents

- What are Seizure Disorders?

- Classification

- Pathophysiology

- Statistics and Incidences

- Causes

- Phases

- Clinical Manifestations

- Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

- Medical Management

- Nursing Management

What are Seizure Disorders?

- Seizure disorders, also known as epilepsy, are a complex and diverse group of neurological conditions that demand specialized nursing care and support. These disorders result from abnormal electrical activity in the brain, leading to recurrent seizures that can vary in type and intensity.

- Seizure disorders can affect individuals of all ages, and they may arise from various causes, such as head injuries, genetic factors, or underlying medical conditions.

- Epilepsy is defined as a brain disorder characterized by an enduring predisposition to generate epileptic seizures and by the neurobiological, cognitive, psychological, and social consequences of this condition.

- One of the earliest descriptions of a secondary generalized tonic-clonic seizure was recorded over 3000 years ago in Mesopotamia; the seizure was attributed to the god of the moon.

- Hippocrates wrote the first book about epilepsy almost 2500 years ago; he rejected ideas regarding the divine etiology of epilepsy and concluded that the cause was excessive phlegm leading to abnormal brain consistency.

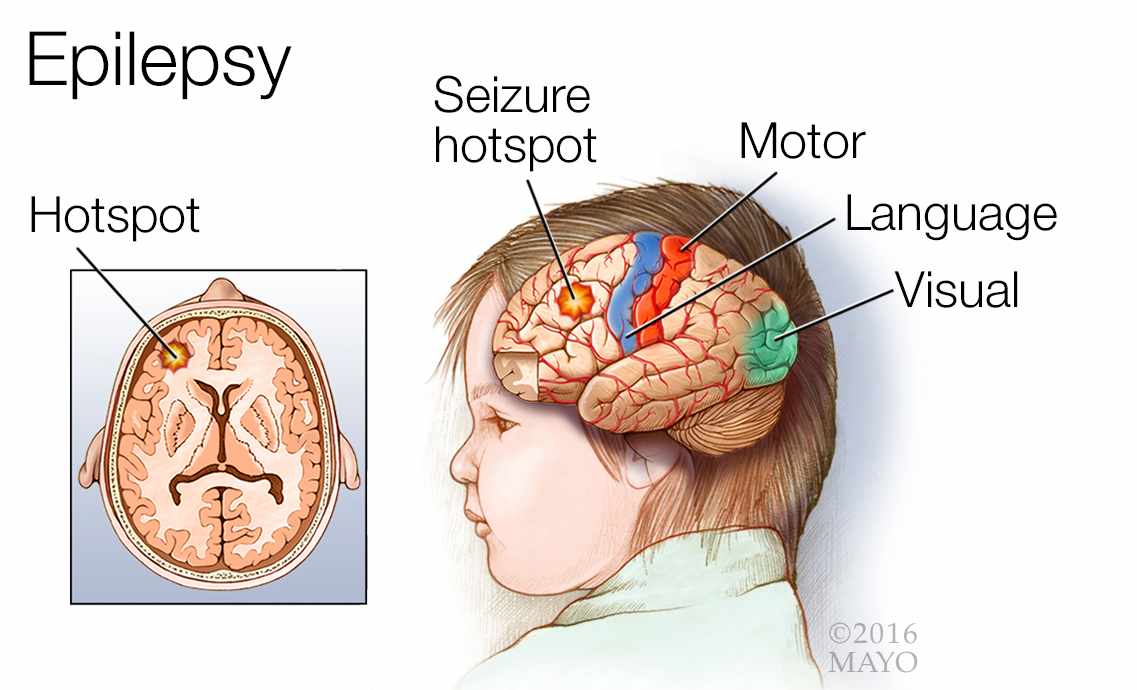

- A seizure is an abnormal, unregulated electrical discharge that occurs within the brain’s cortical gray matter and transiently interrupts normal brain function; a seizure typically causes altered awareness, abnormal sensations, focal involuntary movements, or convulsions (widespread violent involuntary contraction of voluntary muscles).

Classification

Seizures are classified as generalized or partial.

- Generalized seizures. In generalized seizures, the aberrant electrical discharge diffusely involves the entire cortex of both hemispheres from the onset, and consciousness is usually lost; generalized seizures result most often from metabolic disorders and sometimes from genetic disorders.

- Partial seizures. In partial seizures, the excess neuronal discharge occurs in one cerebral cortex, and most often results from structural abnormalities; revised terminology for partial seizures has been proposed; in this system, partial seizures are called focal seizures.

Pathophysiology

Seizures are paroxysmal manifestations of the electrical properties of the cerebral cortex.

- A seizure results when a sudden imbalance occurs between the excitatory and inhibitory forces within the network of cortical neurons in favor of a sudden-onset net excitation.

- The brain is involved in nearly every bodily function, including the higher cortical functions; if the affected cortical network is in the visual cortex, the clinical manifestations are visual phenomena.

- The pathophysiology of focal-onset seizures differs from the mechanisms underlying generalized-onset seizures.

- Overall, cellular excitability is increased, but the mechanisms of synchronization appear to substantially differ between these 2 types of seizure and are therefore discussed separately.

Statistics and Incidences

Incidences of seizure disorders in the United States and worldwide occurs as follows:

- Hauser and collaborators demonstrated that the annual incidence of recurrent nonfebrile seizures in Olmsted County, Minnesota, was about 100 cases per 100,000 persons aged 0–1 year, 40 per 100,000 persons aged 39–40 years, and 140 per 100,000 persons aged 79–80 years.

- By the age of 75 years, the cumulative incidence of epilepsy is 3400 per 100,000 men (3.4%) and 2800 per 100,000 women (2.8%).

- Studies in several developed countries have shown incidences and prevalences of seizures similar to those in the United States.

Causes

In a substantial number of cases, the cause of epilepsy remains unknown.

- Genetic syndromes. A number of genetic syndromes are known to cause seizures; however, a number of more common syndromes should be considered in the patient who presents with seizures and other findings.

- Chromosomal 22q deletion or duplication syndromes. Chromosomal 22q deletion syndrome is a spectrum of findings caused by a deletion on chromosome 22q11.2; seizures occur in 7% of patients with chromosomal 22q deletion syndrome.

- Metabolic disorders. Many different metabolic disorders can cause seizures, some as a result of a metabolic disturbance such as hypoglycemia or acidosis and some as a primary manifestation of the seizure disorder.

- Mitochondrial diseases. Mitochondrial disorders are underdiagnosed but often involve seizures and other neurologic manifestations; mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, and strokelike episodes (MELAS) syndrome is a mitochondrial disorder that is associated with seizures; often, seizures are the presenting manifestation.

- Seizure disorders are caused by single-gene mutations. Autosomal dominant nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy is caused by mutations in the CHRNA4, CHRNB2, or CHRNA2 genes; it is characterized by nocturnal motor seizures.

- Idiopathic or unknown origin.

Phases

The phases of seizure activity are prodromal, aural, ictal, and postictal.

- The prodromal phase involves mood or behavior changes that may precede a seizure by hours or days.

- The aura is a premonition of impending seizure activity and may be visual, auditory, or gustatory.

- The ictal stage is characterized by seizure activity, usually musculoskeletal.

- The postictal stage is a period of confusion/somnolence/irritability that occurs after the seizure.

Clinical Manifestations

The clinical diagnosis of seizures is based on the history obtained from the patient and, most importantly, the observers.

- Aura. An aura (unusual sensations) precedes seizures in about 20% of people who have a seizure disorder.

- Short duration. Almost all seizures are relatively brief, lasting from a few seconds to a few minutes; most seizures last 1 to 2 minutes.

- Postictal state. When a seizure stops, people may have a headache, sore muscles, unusual sensations, confusion, and profound fatigue; these after-effects are called the postictal state.

- Todd paralysis. In some people, one side of the body is weak, and the weakness lasts longer than the seizure (a disorder called Todd paralysis).

- Visual hallucinations. Visual hallucinations (seeing unformed images) occur if the occipital lobe is affected.

- Convulsions. A convulsion (jerking and spasms of muscles throughout the body) occurs if large areas on both sides of the brain are affected.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

Epileptic seizures have many causes, and some epileptic syndromes have specific histopathologic abnormalities.

- Prolactin study. The American Academy of Neurology (AAN) recommends serum prolactin assays, measured in the appropriate clinical setting at 10-20 minutes after a suspected event as a useful adjunct for differentiating generalized tonic-clonic or complex partial seizure from psychogenic nonepileptic seizure in adults and older children.

- Serum studies of anticonvulsant agents. Judicious testing of serum levels of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) may help to improve the care for patients with seizures and epilepsy; however, note that many new AEDs do not have readily obtainable or established levels.

- Neuroimaging studies. A neuroimaging study, such as brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or head computed tomography (CT) scanning, may show structural abnormalities that could be the cause of a seizure.

- Electroencephalography. Interictal epileptiform discharges or focal abnormalities on electroencephalography (EEG) strengthen the diagnosis of epileptic seizures and provide some help in determining the prognosis.

- Video- EEG. Video-EEG monitoring is the criterion standard for classifying the type of seizure or syndrome or for diagnosing pseudoseizures; that is, for establishing a definitive diagnosis of spells with impairment of consciousness.

- Lumbar puncture. Detects abnormal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pressure, signs of infections or bleeding (i.e., subarachnoid, subdural hemorrhage) as a cause of seizure activity (rarely done).

Medical Management

The goal of treatment in patients with epileptic seizures is to achieve a seizure-free status without adverse effects.

- Monotherapy. Monotherapy is desirable because it decreases the likelihood of adverse effects and avoids drug interactions; also, monotherapy may be less expensive than polytherapy, as many of the older anticonvulsant agents have hepatic enzyme-inducing properties that decrease the serum level of the concomitant drug, thereby increasing the required dose of the concomitant drug.

- Anticonvulsant therapy. The mainstay of seizure treatment is anticonvulsant medication; the drug of choice depends on an accurate diagnosis of the epileptic syndrome, as a response to specific anticonvulsants varies among different syndromes.

- Discontinuing anticonvulsant agents. After a person has been seizure free for typically 2-5 years, the physician may consider discontinuing that patient’s medication; many patients outgrow many epileptic syndromes in childhood and do not need to take anticonvulsants.

- Ketogenic diet. The ketogenic diet, which relies heavily on the use of fat, such as hydrogenated vegetable oil shortening (e.g., Crisco), has a role in the treatment of children with severe epilepsy; although this diet is unquestionably effective in some refractory cases of seizure, a ketogenic diet is difficult to maintain; less than 10% of patients continue the diet after a year.

- Atkins diet. Preliminary data have been published about the improvement of seizure frequency following a modified Atkins (low-carbohydrate) diet that mimics the ketogenic diet but does not restrict protein, calories, and fluids; in small studies of children with intractable epilepsy, seizure reductions of more than 50% have been seen within 3 months in some children placed on this diet, particularly with carbohydrate limits of 10 g per day.

- Vagal nerve stimulation. VNS is a palliative technique that involves surgical implantation of a stimulating device; VNS is FDA-approved to treat medically refractory focal-onset epilepsy in patients older than 12 years; some studies demonstrate its efficacy in focal-onset seizures and a small number of patients with primary generalized epilepsy.

- Implantable neurostimulator. The NeuroPace RNS System, a device that is implanted into the cranium, senses, and records electrocorticographic patterns and delivers short trains of current pulses to interrupt ictal discharges in the brain.

- Lobectomy. In a randomized, controlled trial of surgery in 80 patients with temporal lobe epilepsy, 58% of patients in the group randomized to anterior temporal lobe resective surgery were free from seizures impairing awareness at 1 year, as compared with 8% in the group that received anticonvulsant treatment.

- Lesionectomy. In a study presented at the 66th Annual Meeting of the American Epilepsy Society, investigators suggested that, in select pediatric patients, smaller lesionectomy resections in the surgical treatment of seizures may be as effective as larger resections, and they may spare children the functional and developmental deficits associated with the larger resections.

- Activity modification and restrictions. The major problem for patients with seizures is the unpredictability of the next seizure; clinicians should discuss the following types of seizure precautions with patients who have epileptic seizures or other spells of sudden-onset seizures: driving, ascending heights, working with fire or cooking, using power tools and other dangerous equipment, taking unsupervised baths, and swimming.

- Long-term monitoring. In 2018, the FDA cleared for marketing the first smartwatch for seizure tracking and epilepsy management; the Embrace smart watch identifies convulsive seizures and sends an alert via text and phone message to caregivers; the watch also records sleep, rest, and physical activity data; the device was tested in a study of 135 epileptic patients and found the watch’s algorithm detected 100% of patient seizures.

Pharmacologic Management

The number of anticonvulsants has increased, offering many more medication choices for physicians and their patients.

- Anticonvulsants, other. These agents prevent seizure recurrence and terminate clinical and electrical seizure activity; anticonvulsants are normally reserved for patients who are at increased risk for recurrent seizures.

- Anticonvulsants, barbiturates. Like benzodiazepines, barbiturates bind to the gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor, enhancing the actions of GABA by extending GABA-mediated chloride channel openings and allowing neuronal hyperpolarization.

- Anticonvulsants, benzodiazepines. These agents bind to the gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor, thereby enhancing the actions of GABA.

- Anticonvulsants, succinimide. These agents reduce current in T-type calcium channels.

- Anticonvulsants, neuronal potassium channel opener. Stabilizes neuronal KCNQ (Kv7) channels in the open position, increasing the stabilizing membrane current and preventing bursts of action potentials during the sustained depolarizations associated with seizures.

- Anticonvulsants, hydantoins. These agents stabilize sodium channels and prevent the return of the channels to the active state.

Nursing Management

Nursing care for a child with a seizure disorder includes the following:

Nursing Assessment

Nursing assessment includes:

- History. The diagnosis of epileptic seizures is made by analyzing the patient’s detailed clinical history and by performing ancillary tests for confirmation; someone who has observed the patient’s repeated events is usually the best person to provide an accurate history; however, the patient also provides invaluable details about auras, preservation of consciousness, and postictal states.

- Physical exam. A physical examination helps in the diagnosis of specific epileptic syndromes that cause abnormal findings, such as dermatologic abnormalities (e.g., neurocutaneous syndromes such as Sturge-Weber, tuberous sclerosis, and others); also, patients who for years have had intractable generalized tonic-clonic seizures are likely to have suffered injuries requiring stitches.

Nursing Diagnosis

Based on the assessment data, the major nursing diagnoses are:

- Risk for trauma or suffocation related to loss of large or small muscle coordination.

- Risk for ineffective airway clearance related to neuromuscular impairment.

- Situational low self-esteem related to the stigma associated with the condition.

- Deficient knowledge related to information misinterpretation.

- Risk for injury related to weakness, balancing difficulties, cognitive limitations, or altered consciousness.

Nursing Care Planning and Goals

The major nursing goals for a child with a seizure disorder are:

- The patient or caregiver will verbalize understanding of factors that contribute to the possibility of trauma and or suffocation and take steps to correct the situation.

- The patient or caregiver will identify actions or measures to take when seizure activity occurs.

- The patient or caregiver will identify and correct potential risk factors in the environment.

- The patient or caregiver will demonstrate behaviors, lifestyle changes to reduce risk factors and protect self from injury.

- The patient or caregiver will modify the environment as indicated to enhance safety.

- The patient or caregiver will maintain a treatment regimen to control or eliminate seizure activity

- The patient or caregiver will recognize the need for assistance to prevent accidents or injuries.

- The patient will maintain an effective respiratory pattern with airway patent or aspiration prevented.

- The patient or caregiver will demonstrate behaviors to restore positive self-esteem.

- The patient or caregiver will participate in a treatment regimen or activities to correct factors that precipitated a crisis.

- The patient or caregiver will verbalize understanding of the disorder and various stimuli that may increase potentiate seizure activity.

Nursing Interventions

Nursing interventions for a child with seizure disorder include the following:

- Prevent trauma/injury. Teach SO to determine and familiarize warning signs and how to care for the patient during and after a seizure attack; avoid using thermometers that can cause breakage; use tympanic thermometer when necessary to take temperature; uphold strict bedrest if prodromal signs or aura experienced; turn head to side and suction airway as indicated; support head, place on soft area, or assist to floor if out of bed; do not attempt to restrain; monitor and document AED drug levels, corresponding side effects, and frequency of seizure activity.

- Promote airway clearance. Maintain in lying position, a flat surface; turn head to side during seizure activity; loosen clothing from neck or chest and abdominal areas; suction as needed; supervise supplemental oxygen or bag ventilation as needed postictally.

- Improve self-esteem. Determine individual situation related to low self-esteem in the present circumstances; refrain from over-protecting the patient; encourage activities, providing supervision and monitoring when indicated; know the attitudes or capabilities of SO; help an individual realize that his or her feelings are normal; however, guilt and blame are not helpful.

- Enforce education about the disease. Review pathology and prognosis of condition and lifelong need for treatments as indicated; discuss patient’s particular trigger factors (flashing lights, hyperventilation, loud noises, video games, TV viewing); know and instill the importance of good oral hygiene and regular dental care; review medication regimen, the necessity of taking drugs as ordered, and not discontinuing therapy without physician supervision; include directions for a missed dose.

Evaluation

Goals are met as evidenced by:

- The patient or caregiver verbalized an understanding of factors that contribute to the possibility of trauma and or suffocation and take steps to correct the situation.

- The patient or caregiver identified actions or measures to take when seizure activity occurs.

- The patient or caregiver identified and corrected potential risk factors in the environment.

- The patient or caregiver demonstrated behaviors, lifestyle changes to reduce risk factors and protect self from injury.

- The patient or caregiver modified the environment as indicated to enhance safety.

- The patient or caregiver maintained a treatment regimen to control or eliminate seizure activity

- The patient or caregiver recognized the need for assistance to prevent accidents or injuries.

- The patient maintained an effective respiratory pattern with airway patent or aspiration prevented.

- The patient or caregiver demonstrated behaviors to restore positive self-esteem.

- The patient or caregiver participated in treatment regimen or activities to correct factors that precipitated a crisis.

- The patient or caregiver verbalized understanding of the disorder and various stimuli that may increase potentiate seizure activity.

Documentation Guidelines

Documentation in a child with seizure disorder include:

- Individual findings include factors affecting, interactions, the nature of social exchanges, and specifics of individual behavior.

- Cultural and religious beliefs, and expectations.

- Plan of care.

- Teaching plan.

- Responses to interventions, teaching, and actions performed.

- Attainment or progress toward the desired outcome.

Good job…interesting notes….

Uff too tough vocabulary! Other disease description is really good

Good one

thank you very much

Hi Junior, You’re welcome! Glad the information on seizure disorders was useful to you. Just a quick nursing tip: Always prioritize safety during a seizure. Clear the area of any harmful objects and place something soft under the person’s head. Remember, don’t try to hold them down or put anything in their mouth. If you have more questions or need further advice, feel free to ask. Always here to help!