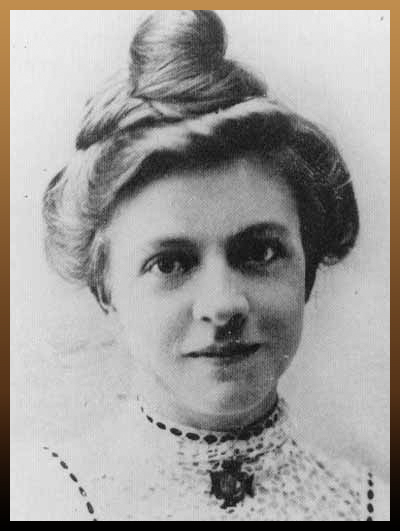

Nurse Clara Louise Maass gave up her life in 1901 in a scientific endeavor to prove that mosquitoes are vectors of yellow fever. Few realize that her death was also a turning point in favor of the US expansion in Cuba, the Caribbean, and Latin America.

While Maass has received considerable recognition as a dedicated, fearless, self-sacrificing nurse, her contribution to the control of yellow fever and US history has received little acknowledgment.

The Story of Clara Maass

Clara Louise Maass was born in East Orange, New Jersey on June 28, 1876, the eldest of nine children to a family who came from Europe to form part of the German diaspora seeking religious freedom and better opportunities. Clara assumed early her responsibilities to provide for her family. At age 10, she was a “mother’s helper” and lived in another’s home without pay except for room and time to be allowed to go to school. At age 15, she was employed at the Newark Orphan Asylum with a meager salary for working seven days a week caring for orphans.

Career opportunities were limited at that time for a young woman but Clara Louse, inspired by Florence Nightingale‘s dedication, enrolled in a nursing school at age 17. She became one of the first nurses to train Christina Trefz Training School for Nurses at Newark German Hospital, graduating in 1895. She was promoted to head nurse at the hospital three years later.

Later that same year, she volunteered and was selected to join the US Army as a contract nurse. The need for nurses during the Spanish-American War was so great that the Army could not recruit enough preferred male nurses and has to turn to trained white female nurses as a last resort. One of the critical selection criteria for the contract nurses was training in aseptic and antiseptic techniques – more soldiers died from infectious diseases, notably typhoid, than from battle wounds.

Maass served in the various army camps in the US and Cuba until the beginning of 1899. She served again from late 1899 to 1900 in the Philippines where she contracted Dengue fever and was sent home seven months later to recuperate. She returned to Cuba later in 1900 after being summoned by Dr. William Gorgas who was working with the US Army’s Yellow Fever Commission.

Here she was the only woman to volunteer in an experiment to determine whether mild infection with yellow fever would provide immunity. She thought that having the disease herself would make her a better nurse. After allowing herself to be bitten by a yellow-fever-infected mosquito, she contracted the disease and recovered. She continued with the experiment, and after being bitten three more times, she became seriously ill and passed away at the young age of twenty-five.

Clara Louise Maass died as she had lived — for others.

The Yellow Fever Experiments

Migrants, smuggling, and trade from Cuba were believed to be responsible for the outbreaks of yellow fever in the Southern States of the US – and its devastating social and economic consequences.

The control of Cuba in order the contain the spread of the disease was the main driving force behind the US invasion of that country. The US Army established a Yellow Fever Board responsible for finding the means of transmission of yellow fever and how to control the disease. The researchers soon became convinced that yellow fever was transmitted by the Aedes Aegypti mosquito.

Eradication measures were started in Havana by the city’s sanitation department but there was resistance from the public. They did not believe that the mild experimental form of the disease was the same as its wild, virulent form.

Dr. Juan Guitéras then wanted to determine whether a mild form of yellow fever would provide immunity against this disease. For this, he would need non-immune human volunteers (as all animals at the time seemed immune to yellow fever). Volunteers would receive $100 for allowing themselves to be bitten and another $100 if they became sick.

Eight volunteers contracted yellow fever after being bitten by an infected mosquito. One of these volunteers and the only woman was Clara Louise Maass. She believed that she would be more useful as a nurse and have a greater sense of understanding of yellow fever after having contracted the disease and becoming immune.

Clara Maass then volunteered to be bitten a further three times. After the third time, she developed a virulent strain of the disease and became seriously ill. Sensing the seriousness of her condition, she wrote to her mother saying:

Goodbye, Mother.

Don’t worry. God will take care of me in the yellow fever hospital the same as if I were home.

I will send you nearly all I earn, so be good to yourself and the two little ones.

You know I am the man of the family, but do pray for me.

A few days later, she passed away at the age of twenty-five. She was the last of three volunteers to die from this experiment, after which it caused controversy and the human trials were stopped. Because Maass was the only woman, American and nurse to have died in the US yellow fever experiments her death led to the most publicity.

Clara Maass’ death finally convinced the public of Havana of the mosquito theory. They started cooperating with the sanitation department to rid the city of mosquitoes and subsequently of yellow fever.

“Her death potentially serves as a significant event in the history of colonial medicine in Cuba,” wrote Manuel Jusino. “With the suppression of yellow fever in Havana, the U.S. proved that it could transform what was once believed to be a ‘diseased’ city into a viable center for U.S. expansion.”

The control of yellow fever in Cuba also paved the way for turning much of the Caribbean and Latin America into territories contributing to the economic growth of the US.

Clara Maass’ True Contribution

The public of Havana only became convinced of the link between A. aegypti and Yellow Fever — on the authority of Maass’ death rather than on the prior claims by military leaders. Her contribution as a significant figure in the history of controlling yellow fever throughout the world, and in Cuban-American relations, remains largely unacknowledged.

Maass was not included in a law passed in 1929 to recognize the high public service of those associated with the discovery of the cause and transmission of yellow fever, nor in amendments to the law in 1956 and 1958, one of which included a male contract nurse.

Maass has received recognition, but the theme of the faithful nurse with the sacrificial spirit dominates the story. Clara Louise Maass was serving her country in the time or war, caring for the sick and wounded and, finally, sacrificing her life in her belief that she could be a better nurse.

“As a woman, Maass was thus characterized as allegedly subordinate to her male physicians, and instead epitomized on a Victorian pedestal of virtue and benevolence,” writes Jusino. “Maass’ historical contribution is open to further investigation. What would it mean to give Maass’ life and death real agency in the Cuban-American yellow fever narrative?”

Throughout history, major contributions by women have been similarly minimized within the culture of a male-dominated society. Can our generation use our voice to bring changes to this scenario?

Leave a Comment