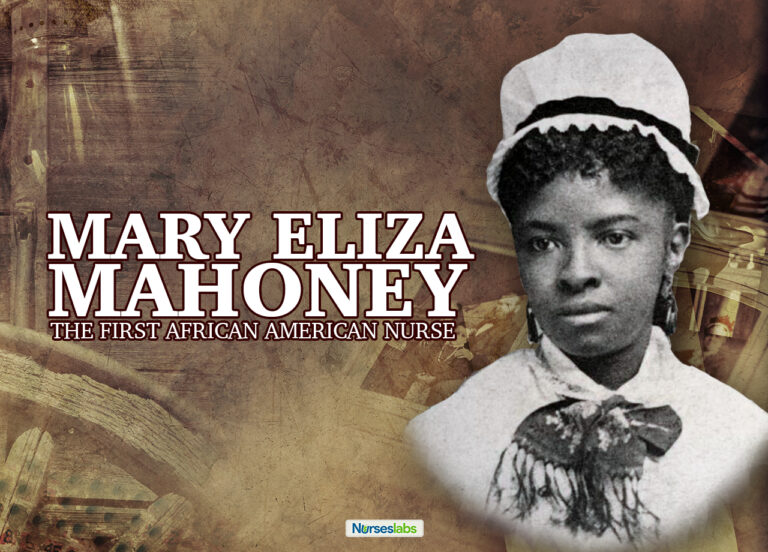

Mary Eliza Mahoney became the first professionally qualified black nurse in 1879. Besides being acknowledged as an excellent nurse, she continued throughout her life making her mark as an activist for the rights of minority nurses and women.

Early Life

Mary Eliza Mahoney was born on May 7, 1845, in Dorchester, Massachusetts, to freed slave parents who had moved north wanting to live in an environment with less racial discrimination. Mahoney’s small stature – weighing in at around 90 pounds – did not limit her energy and drive. She was a deeply religious woman, which was also the reason why she aspired from a young age to become a nurse.

Mahoney started work at the New England Hospital for Women and Children at age 18 and worked there for 15 years as a cook, maid, and washerwoman before starting her training as a nurse. At the age of 33, Mahoney was the first black woman to be accepted into the Hospital’s 16-month training program in 1878.

New England Hospital for Women and Children was the first institution in the US to introduce a formal nurse training course in 1872. The hospital was founded and staffed entirely by women physicians, and it’s possible that this other minority group – women in medicine – gave Mahoney the opportunity because they were also victims of prejudice.

Career

Out of a class of 40 entrants, Mary Eliza Mahoney graduated as one of only four students to complete the intensive program and became the first black professionally qualified nurse. For the next 30 years, she worked mainly as a private duty nurse in the homes of wealthy white families. She was praised for her efficiency and calm approach and her reputation spread to the extent that the received calls for her services from across many US states – including Massachusetts, New Jersey, Washington, and North Carolina. Throughout her career, she took pride in her work, driven by the belief that it was important to prove that there was no place for discrimination in the nursing profession.

From 1911-1912, at age 66, Mahoney took up the position of supervisor at the Howard Orphan Asylum for Black Children in New York after which she retired in Boston. She remained involved in activism for nurses’ and women’s rights. At the age of 76, she was one of the first women in Boston who registered to vote after the passing of the 19th amendment which gave women the right to vote.

After a three year battle with cancer, on January 4, 1926, Mahoney passed away at age 81. She was buried in the Woodlawn Cemetery in Everett, Massachusetts.

The legacy of Mary Mahoney

Mahoney was also active in nursing organizations, and it has been said that she seldom missed a national nurses’ meeting. In 1896, she became one of the first black members of the Nurses Associated Alumnae of the United States and Canada (later renamed the American Nurses Association).

Mahoney recognized the importance for nurses to stand together in improving the status of blacks in the profession. She was a co-founder of the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses (NACGN) – an organization with the aim of advancing the interests of colored nurses and eliminating racial discrimination in the profession. At the first NACGN convention in 1909, Mahoney delivered the welcome address in which she made a passionate plea against inequalities in nursing education and called for demonstrations to have more African-American students admitted to nursing schools.

In Mahoney’s honor, the NACGN established the Mary Mahoney Award in 1936 to recognize contributions to advancing the interests of black nurses. The medal was continued after the organization merged with the ANA in 1951. Today the ANA presents the award “in recognition of an individual nurse or group of nurses for special efforts they have made towards increasing diversity and inclusion within the nursing profession.”

Helen Sullivan Miller, a recipient of the medal in 1968, was inspired to visit Mahoney’s grave in Everett, Massachusetts. After it took her some time to find the simple marker, she launched a drive for a proper monument to Mary Eliza Mahoney and the gravestone was dedicated in 1973.

Mahony was inducted into the American Nurses Hall of Fame in 1976 and into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in 1993.

“Today’s minority nurses stand on the shoulders of Mary Mahoney,” said May Wykle, one for the recipients of the medal and dean and professor of nursing. “She was a true pioneer in nursing, and we owe a debt of gratitude for her being a determined role model.”

There is/are some problems with this article. First, check the dates on the comment regarding her parents moving north after the Civil War. The Civil War ended in 1865, yet the author’s comments seem to indicate a different date. Second the comment, the fact that she, “graduated one out of only four of a class of 40 is also confusing. Were there only 4 how completed the full course of study or what? As a person who is somewhat familiar with Mary Eliza Mahoney, I am attempting to understand, but these problems of the author are very distracting and do not lend credence to the whole article.

Hi Gracie,

Thank you very much for your comment. That Mahoney’s parents had moved after the Civil War was indeed my mistake and it has been corrected.

Concerning the fact that Mahoney was only one in four to pass the course had me sitting up as well when I first read it, but it was confirmed in numerous sources. It seems that it was the general pattern for the course which was very though – the majority of the students fell out along the way. The numbers differ slightly between sources, some saying that she was one in three who completed, and with the original number of students varying between 39 and 45. A source quoting the figure I mentioned in the article, and which appears to be a reliable source, has been linked in the article.

Thanks for clarifying this, Frieda.