Never before have those of us who are alive today experienced the demands and the collective shock, grief, and feeling of helplessness brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic. But this isn’t the first global disaster caused by an unusually deadly virus – a century ago, the Spanish influenza became the most devastating pandemic in human history. The devastating influenza pandemic of 1918-1919 was a crucial time for nursing and its influence on the nursing profession is still felt up to this present day.

COVID-19 deaths will probably be far lower than those from the Spanish Flu because of the unprecedented advances in science and communication during the past 100 years. Nevertheless, there are many striking similarities – in the lack of effective treatment options, the public health measures used to control the spread, and the enormous demands on the nursing profession.

The Spanish influenza pandemic

The Spanish influenza struck the world in 1918, just as World War I was drawing to a close. The world’s attention was focused on the war and its aftermath, and very little was recorded about the epidemic at the time. Researchers have only started to delve into the history of the Spanish flu over the past few decades.

Global infectious disease statistics were not kept in those days as they are today. Estimates are that around 500 million people, between a quarter and a third of the world’s population at the time, were infected and that about 50 to 100 million of them died. The deaths were more than all those killed during World War I and World War II. It also killed far more people than the infamous bubonic plague of the middle ages, or than have been killed by HIV/AIDS to date.

The term Spanish influenza was actually a misnomer as research has shown that the disease did not originate in Spain, but most probably in the US. The name is ascribed to the fact that the King of Spain, Alfonso XIII, was an early victim of the disease and this became frontpage news across the world. In most other countries, there was strict wartime censorship of the press and the epidemic proportions of the Spanish Flu, initially among soldiers, were seldom reported on.

A first wave of the Spanish Flu occurred in the spring of 1918, mainly in army camps. Apparently, it died down fairly rapidly and no further attention was given to the disease. In the fall of that year, a more virulent strain of the virus appeared to take hold. Overcrowded and unsanitary conditions in army camps contributed to the rapid spread of the disease. From there, as soldiers returned to their home countries, the virus was carried to nearly every corner of the world.

What was the Spanish Flu?

Public health officials and doctors had very little understanding of the disease and were baffled by the fact that the Spanish Flu was so much more virulent and deadly than the usual seasonal flu. Furthermore, it characteristically killed more young and healthy adults compared to the usual victims of influenza – the children and the elderly.

Medicine had accepted the germ theory of infectious diseases, but the fact that viruses also caused disease in man was still unknown. Analysis of a recently discovered preserved sample, from a soldier who died from the Spanish flu, found that it was caused by a strain of H1N1 virus, the same virus which was responsible for the outbreak of the swine flu in 2009.

Those infected with the virus initially showed symptoms of ordinary influenza but quickly became very ill with a high fever and fluid collecting in their lungs. A distinctive symptom of the Spanish Flu was heliotrope cyanosis, which was dark blue or purple coloring spreading across the body. Once this acute respiratory distress set in, death was usually inevitable. “It is simply a struggle for air until they suffocate,” wrote a doctor at the time.

Public Health measures to control the spread

Measures to limit contact between humans to curb the spread of infectious diseases had been used since the middle ages and similar restrictions were implemented during the Spanish Flu. It was mostly up to the local authorities to decide what measures to take with the result that responses varied greatly between cities, areas, and countries.

Measures introduced included banning large public gatherings and closing down schools, cinemas, saloons, dance halls, and streetcars. In some cities, the public was also encouraged to stay at home and affected individuals were generally placed under quarantine.

Furthermore, the public was educated to avoid crowds, to use handkerchiefs to cover their nose and mouth when coughing or sneezing and to practice good hygiene by hand washing. Some authorities also encouraged increasing natural resistance to the disease through sufficient rest, fresh air and good nourishment.

In Minnesota, volunteer teachers, Boy Scouts, and postal workers were used to educate the public by helping to put up posters and distributing educational pamphlets.

San Francisco passed an ordinance by which everyone had to wear a gauze mask when venturing outside and this apparently led to a rapid decline in the number of cases. The following rhyme was used to remind people to wear their masks:

Obey the laws

And wear the gauze

Protect your jaws

From Septic Paws.

Members of the public varied in their reactions to stringent measures which impacted their daily lives. Some accepted the restrictions, others called for stricter measures, and then there were also those who protested against what they saw as unnecessary and unfair limitations.

Some public health authorities were slow to respond. For example, when the Spanish Flu had already taken a firm hold and claimed a number of lives in the city, the Director of Public Health and Charities in Philadelphia insisted that there was nothing to worry about and a mass Liberty Bond Parade went ahead. Tens-of-thousands of people flocked to the streets and a spike in cases of Spanish Flu was seen within days. Philadelphia was one of the hardest-hit cities in the US.

Overall, analyses of records show that death rates were lower where various measures were implemented quickly and sustained over time.

Treatment for Spanish influenza

There was no effective treatment or vaccine for Spanish influenza. Doctors experimented with different treatments previously used for respiratory diseases. These included quinine, camphor, whiskey, creosote with its known antiseptic properties, and even strychnine. General medicines for symptomatic treatment such as aspirin, calomel, and castor oil were also used.

The public obviously also used their own traditional and folk remedies. And then there were also the usual “cures” promoted by con-men to line their pockets.

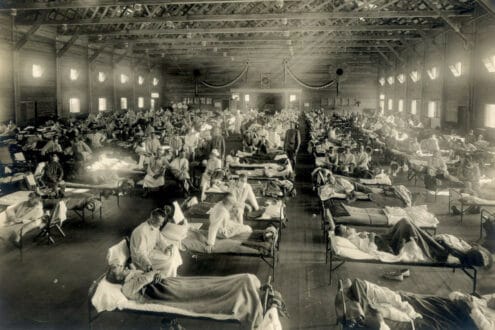

Hospitals, and even temporary facilities, were soon overwhelmed with the result that only the most severe patients were admitted, and others were cared for at home by visiting nurses and volunteers

Various isolation and infection control measures were used in hospitals. These included ensuring good ventilation, separation of beds, reducing the number of beds in wards, arranging the beds so that patients faced head to foot, and hanging sheets between beds.

Further measures included disinfection of bedding and rooms, staff disinfecting their hands with antiseptic hand solution, and the introduction of gauze masks.

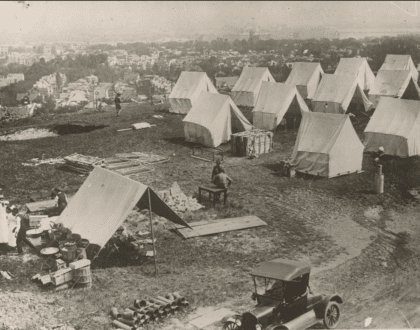

The treatment and infection control measures at the Camp Brooks Hospital are noteworthy because of the low fatality rate amongst both patients and health care staff. This tent hospital admitted a group of 351 sailors of whom many were already suffering from pneumonia.

During the day the patients were nursed mainly outside in the fresh air and sunshine and at night the tent flaps were left open, with patients supplied with extra blankets and hot-water bottles to stay warm. Sunshine is known to kill bacteria and viruses, and the “fresh air factor” was the subject of serious research until antibiotics were discovered.

Patients used their own dishes and utensils, which were cleaned with boiling water after each use. Staff had to clean their hands with disinfectant after each patient contact and no sharing of cups, towels or other items was allowed. They wore gowns, gloves, head coverings, and masks while in contact with patients.

The special improvised masks are of particular interest. The wireframe was made from a gravy strainer to fit each individual’s face so that the gauze covering didn’t touch the mouth or the nose. Staff were not allowed to touch the outside of the masks and they were replaced, sterilized and covered with fresh gauze every two hours.

Before the outbreak of the pandemic, medicine had made great strides in the preceding few decades and was gaining a reputation for being able to cure disease. Faced by the Spanish Flu, however, doctors were at a loss and had to admit that there was nothing they could do. What soon became evident, however, was that nurses were the ones who could make a difference on the front lines.

Nursing during the Spanish Influenza

Where there was no effective medical intervention, nursing skills could provide comfort and basic care – monitoring vital signs, ensuring proper ventilation, disinfecting, bathing and changing linen, personal hygiene, feeding, emotional support, educating, and more – until the patient recovered or passed away.

By 1918, nursing education had become well established – in the US there were already 1129 training schools by 1910. Despite this, there was an acute shortage of trained nurses to meet the demands of the Spanish Flu. Furthermore, many of the trained nurses were still serving in the military and large numbers of health care workers became infected and even lost their lives.

Centralized response to the epidemic was not from the federal government but from the American Red Cross. This organization created a National Committee on Influenza to coordinate the distribution of nurses and volunteers, as well as medical supplies, across the US. Nevertheless, requests from various areas for additional nurses often went unfulfilled, as illustrated by the following telegraphic message “Can send all the Doctors you want but not one nurse.”

Besides working in hospitals, thousands of nurses served communities as health visitors in cities as well as in remote areas. Nurses were often the only health care providers as doctors were unable to reach everyone that was ill. Nurses reported that they worked up to 18 hours a day, or until they could no longer stand.

Visiting nurses would enter homes to find whole families critically ill with the flu, some even already dead. “The people watch at their doors and windows, beckoning for the nurse to come in. One day a nurse who started out with fifteen patients to see, saw nearly fifty before night,” a nurse wrote at the time.

The Red Cross also engaged volunteers to help care for the sick because of the shortage of trained nurses, sometimes providing them with some basic training. The public, however, soon realized the value of trained nurses even though the treatment was only symptomatic. “One trained nurse is worth a score (20) of untrained volunteers”, reported one newspaper. Access to skilled nursing care was widely reported as the best predictor of survival.

How was the nursing profession influenced by the Spanish Flu?

Before the epidemic, the nurse’s role was most often seen as that of executing the doctor’s orders. During the Spanish Flu, doctors could offer no effective treatment and were frequently not even able to get to all the patients.

Nurses could exercise the skills of their profession and it became abundantly clear that they had their own unique role in caring for patients. Nurses were capable of independent judgment and action. Nurses kept watch over their patients and, when their condition changed suddenly, a nurse had to “act immediately with knowledge, with control, and with authority.”

Nurses found new meaning in their profession, they were proud of what they had achieved during the epidemic. “Terrible as was the influenza epidemic, with its frightful toll, there was a certain tremendous exhilaration to be felt as well as many lessons to be learned from such a terrific test,” one nurse wrote.

A further change brought about by the use of volunteers during the epidemic was the introduction of a second category of nurse – the licensed practical nurse, as we know it today.

Across the world health authorities also accepted the need for stronger public health systems, with a number of countries enacting central public health legislation shortly afterward. This led to an increase in the number of nurses engaged in community health services.

Lessons from the Spanish Flu and COVID-19

The Spanish influenza highlighted the role of the nurse internationally. The pandemic raised the status of the nursing profession and it became a route for nursing to claim greater professional recognition in the early 20th Century.

As nurses, we have surely all been struck by the irony of a pandemic during 2020 The Year of the Nurse and Midwife. The need for greater recognition of nurses and alleviating the shortages could, however, not have been better illustrated than through the COVID-19 pandemic.

Looking at global preparation for a pandemic, and the initial reactions of many policymakers to COVID-19, it appears that the world did not pay enough attention to the many lessons it could have learned from the Spanish influenza. Including those associated with the nursing profession.

Hopefully, the lessons of the current pandemic will not rapidly fade away from collective memory and that governments and policymakers will take them seriously far into the future.

So well written, Frieda! I really enjoyed reading this. Regards from this side, Wilma Kotze

Thank you Wilma. The topic came up because I was curious and wanted to do the research – really enjoyed it!

Hi Frieda, good job! I love this article and I found passion on it. So informatic and well written. Oh ya, I’m an Indonesian Registered Nurse and have an educational nursing web too,may I re-post this to my web and translate it into my own language? With your credit of course, would you mind?

Compared to most other articles, I can safely say that I appreciate the statistical usage and informational education. I highly suggest ‘The Great Influenza’ By: John M. Barry. A fascinating read that delves into the nursing shortage of 1918 H1N1.

Many outstandingly startling occurrences also occurred, for example in an instance in Philadelphia stated that 2,955 calls were received in a day for nurses and 2,758 were unfulfilled. The patients of 1918 H1N1 during the lethal fall wave would have oedematous lungs that would have fluid filled to the trachea.

The lungs would be soaked with so much blood from haemorrhaging that the lung tissues couldn’t absorb oxygen and expand any longer causing patients to die of asphyxiation. Also, some fibrosis tore small little lesions in the lung pleura to the point that air would leak out and collect under the skin of the infected.

When nurses and doctors rolled these patients over or moved them, the air bubbles in the skin would crackle and pop like rice krispies. Patients would constantly be in fevered delirium and have severe nosebleeds – some having blood shoot out by 2 feet. The cyanosis would be so bad that it was almost impossible to discern whites and blacks.

On top of this, significant pulmonary hepatization prevented alveoli to absorb oxygen and the ARDS prevented diffusion of it into the bloodstream. Some had such extreme bone aches that they misdiagnosed it as Dengue Fever, also known as breakbone fever. That name comes because some Dengue victims capillaries are aggregated near the location of bone formation and metabolism, causing them to bleed and crack.

Some misdiagnosed it as Cholera for how violent some gastrointestinal cases were. Or malaria because of how hyperpyrexic, fatigued and septic some patients were. Some cases were even haemorrhagic like Ebola Zaire or Yellow Fever cases.

The virus damaged pulmonary lung lining so if you survived the original infection of 1918 H1N1, you most likely would be killed by secondary bacterial pneumonia. You were significantly more likely to die if you were younger and healthier as well. Due to a positive feedback-loop between cytokines and immune cells, a cytokine storm occurred which caused the immune system to keep inflaming and attacking the infection with Scorched-Earth tactics – killing so much of itself in the process.

In India, no more wood was left to burn with the infected that the bodies were dumped into rivers until it clogged them. People would be stuck in their homes and forced to live with the dead putrefactive corpses of those they loved, eating and sleeping next to them.

Personally what I think this teaches us is how Nurses are the most needed health professionals in an outbreak of almost any kind – as for nurses compared to doctors could help patients actually feel significantly better by comforting them, making them comfortable and relaxed, hydrating and caring for them. Even if at their bed-side for a few minutes, they could still help significantly. People would actually start kidnapping nurses in their homes.

Paul Lewis had taken a cable car and on it multiple people collapsed and dropped dead out of nowhere and once the driver and conductor both dropped dead, Paul Lewis got off and walked the next few miles home on foot. This also was followed by Encephalitis Lethargica which killed 1/3 of people who experienced it and zombified people in very traumatizing ways. Influenza Psychoses was also extremely mentally scarring for those experiencing it and those around them. I could go on and on, but really what I just think is how insane nurses impacted this, or could’ve. I hope humanity learns its lesson as there are lots of them to learn here.