Becoming an Emergency Room Nurse in the United States is a rewarding career path with dynamic clinical experiences, strong job demand, and the chance to make a lifesaving impact. ER nurses work on the frontlines of acute care – one shift they might stabilize a car accident victim, and the next they could be managing a patient’s heart attack. It’s a fast-paced role where nurses triage arriving patients, perform urgent interventions, and collaborate with doctors and first responders to treat everything from broken bones to life-threatening injuries.

This article explores what an ER nurse is, how to become one, the costs involved, daily roles and responsibilities, salary and job outlook, specialized tracks, professional resources, key skills, and the pros and cons of this career.

What Is an Emergency Room Nurse?

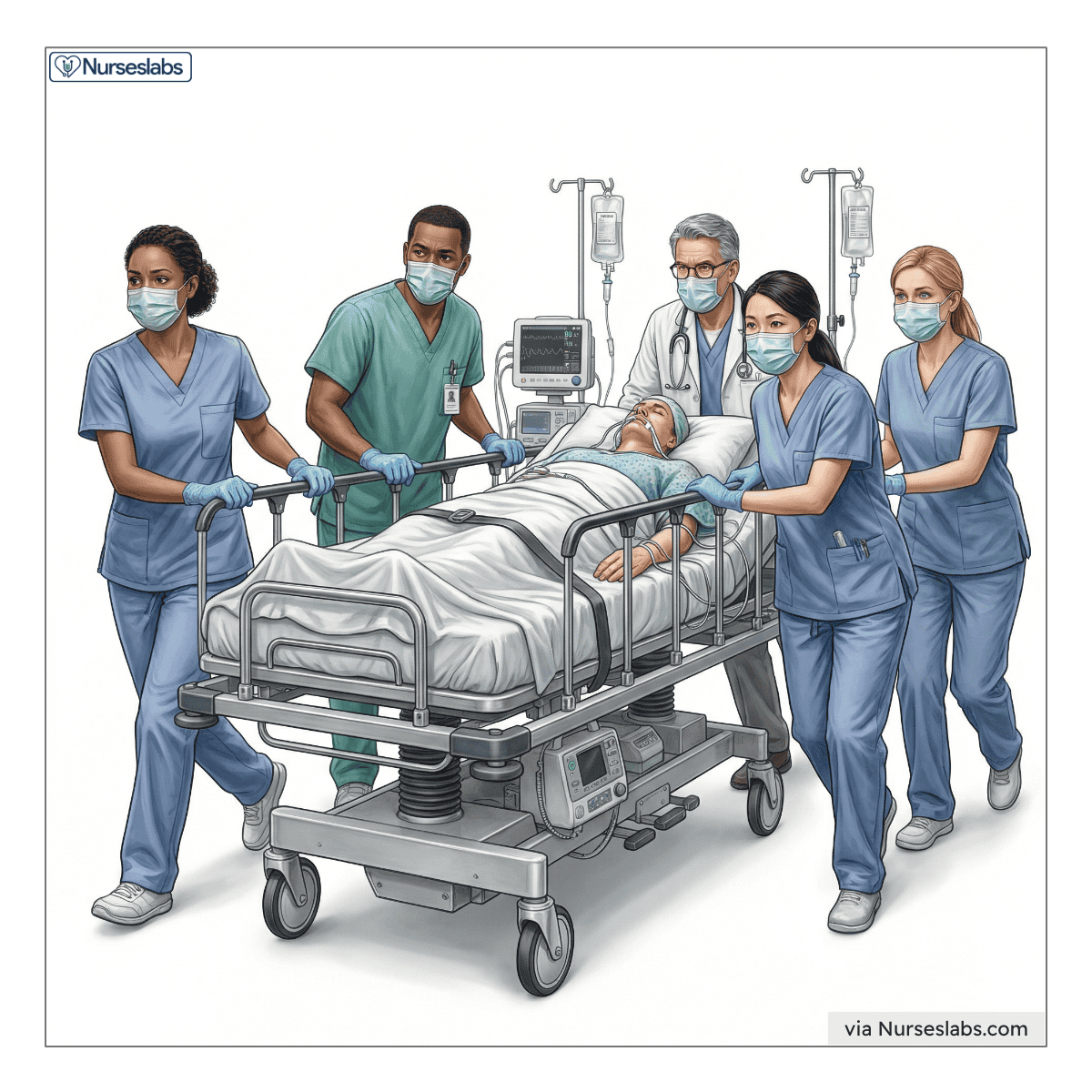

Emergency Room Nurses (ER nurses) are registered nurses who specialize in acute, urgent patient care in hospital emergency departments and trauma centers. They are often the first medical professionals to assess and treat people in a health crisis. ER nurses handle patients of all ages with a wide range of injuries and illnesses, from minor lacerations to major traumas. Unlike nurses on scheduled hospital floors, ER nurses never know what will come through the door next – they must rapidly triage patients (decide who needs immediate care), provide critical interventions, and multitask under pressure. In essence, an ER nurse is a jack-of-all-trades RN prepared for any emergency.

An ER nurse must be a licensed Registered Nurse (RN), typically with a Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) or Associate Degree in Nursing (ADN). After passing the NCLEX-RN exam to obtain an RN license, they often receive additional training in emergency care protocols (such as Advanced Cardiac Life Support and trauma care courses). ER nurses work as part of a team under the direction of physicians and must follow hospital protocols, but they have considerable autonomy in performing nursing interventions quickly. For example, they may start IV lines, administer medications, and activate specialty teams (like a stroke or trauma team) based on their assessment. While nurse practitioners (NPs) can also work in emergency settings (often called emergency nurse practitioners), a standard ER nurse is an RN – not an advanced practice provider – so they do not diagnose medical conditions or prescribe treatments independently.

Emergency room nurses differ from nurses in general medical-surgical units by the intensity and breadth of cases they handle. A medical-surgical RN might manage patients with one or two stable conditions on a set floor, whereas an ER RN might simultaneously care for a child with an asthma attack, an adult with chest pain, and a trauma victim. ER nurses also coordinate frequently with EMTs/paramedics (who bring patients in) and must make split-second decisions – skills less demanded in routine inpatient settings.

Compared to Trauma Nurses, who specifically focus on patients with severe injuries (often in designated trauma centers), ER nurses treat all types of emergencies including medical crises (like heart attacks or strokes) in addition to injuries. In practice, many ER nurses are also trauma nurses if they work in Level I trauma centers, but trauma specialists might pursue extra certifications to focus primarily on injury care.

The Emergency Nurses Association (ENA) describes emergency nursing well: “Emergency nurses work in stressful, fast-paced, and time-constrained environments where they integrate evidence-based knowledge, make rapid assessments, make critical decisions, and perform life-saving interventions while prioritizing and multitasking.” In short, ER nurses thrive on adrenaline, broad knowledge, and teamwork to care for patients in their most critical moments.

To illustrate the impact and scope of emergency nursing, consider that U.S. emergency departments handle around 140 million visits per year. ER nurses are the frontline responders for each of those visits – stabilizing patients, alleviating pain, and often saving lives in situations where every second counts. It’s a role that demands excellent clinical skills, resilience, and compassion in equal measure.

How to Become an Emergency Room Nurse

The path to becoming an ER nurse involves building a foundation as a registered nurse, gaining experience, and potentially earning specialized credentials. Below is an overview of the typical steps to enter emergency nursing, from education to licensure and beyond:

1. Earn Your RN License

Complete an accredited nursing program (ADN or BSN) and pass the NCLEX-RN exam to obtain your RN license. This is the baseline requirement for any nursing specialty. Many aspiring ER nurses opt for a BSN degree, as some hospitals prefer or require BSNs for emergency department roles.

| Stage | Typical Duration | Milestones & Requirements |

|---|---|---|

| Nursing Education (ADN or BSN) | 2–4 years (full-time) | Complete an accredited nursing program; take coursework in anatomy, pharmacology, etc.; complete clinical rotations (including an ER rotation if available). |

| NCLEX-RN & Initial RN License | ~2–3 months (exam prep & licensure) | Register and sit for the NCLEX-RN exam ( $200 fee) after graduation; pass the exam to earn RN licensure; apply for state RN license (fees ~$100–$200, varies by state). |

| Entry-Level RN Experience | 1–3 years | Work as an RN in a hospital setting. Common routes: start in an ER Nurse Residency program (if available) or begin on a Med-Surg/ICU floor to build skills. Develop proficiency in IV starts, patient assessment, multitasking, and emergency protocols. |

| Advanced Education (Optional) | 2–3 years (if pursuing MSN/DNP) | (Optional step for advanced roles.) Enroll in a graduate program for Emergency NP or related field. Complete advanced coursework and clinical hours in emergency care. Graduate and pass any required certification exams for NPs or CNS roles. |

| Emergency Nursing Certification | Prep: ~3–6 months (after 2+ years experience) | Study for and pass the CEN exam (Certification in Emergency Nursing). Requires RN license and recommended 2 years of ER experience. Earning CEN demonstrates expertise. Also complete life support courses (BLS/ACLS/PALS) and trauma courses (TNCC). |

| Maintain License & CE | Ongoing (career-long) | Renew RN license every renewal cycle (typically 2 years) with required CE hours (e.g. 20–30 hours, depending on state). Stay updated via emergency nursing conferences, online courses, and employer training. Maintain any certifications (CEN renewal every 4 years via exam or CE credits). |

Tip: If you’re eager to jump into ER nursing, look for hospitals with new graduate ER internships or residency programs. These programs provide extra training and support for new RNs transitioning directly into the emergency department. Even if you start elsewhere, you can always transfer into the ER after gaining some experience – many successful ER nurses begin on general floors or ICUs and make the switch when they feel ready.

2. Gain Clinical Experience

Start working as an RN, ideally in a hospital setting. Some new grads begin directly in the ER if a residency or orientation is offered, while others gain 1–2 years of experience in medical-surgical or critical care units to build strong fundamental skills before transitioning to the emergency department. Hands-on experience with IVs, cardiac monitoring, wound care, and fast-paced decision-making is invaluable.

3. Consider a Graduate Program (If Needed)

While not required to be an ER staff RN, a graduate nursing program is necessary if you plan to advance as an Emergency Nurse Practitioner or Clinical Nurse Specialist in emergency care. For example, an ER nurse who wants to diagnose and prescribe would need a Master’s or Doctorate (MSN or DNP) in an NP program (such as Family or Acute Care NP) with emergency specialty training. This step is optional unless pursuing advanced practice or leadership roles.

4. Obtain Emergency Nursing Certification

After 1–2 years of emergency experience, many ER nurses strengthen their credentials by earning specialty certification. The most recognized is the Certified Emergency Nurse (CEN) certification, administered by the Board of Certification for Emergency Nursing. The CEN exam covers trauma, cardiac, pediatric, and other emergency topics. Certification is often voluntary but highly regarded – it demonstrates expertise and can sometimes come with a pay increase. Other relevant certs include Trauma Nursing Core Course (TNCC) completion, Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support (ACLS), Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS), and for pediatric focus, Certified Pediatric Emergency Nurse (CPEN).

5. Secure State Licensure & Credentials

Ensure you have an active RN license in the state where you plan to practice. ER nurses must be licensed in their state (or hold a multi-state license if in a Nurse Licensure Compact state). If you pursued advanced practice, you’ll also need to obtain state NP licensure and any prescriptive authority as required. For most ER RNs, maintaining the standard RN license (renewed every 2–3 years with fees and continuing education) is the main requirement.

6. Pursue Continuing Education (CE)

Emergency nursing is continually evolving. ER nurses stay current through continuing education courses and training. State boards typically require RNs to complete a certain number of CE hours for license renewal. Additionally, hospitals often provide ongoing in-service training on the latest protocols (for strokes, sepsis, disaster preparedness, etc.). Maintaining certifications like CEN also requires periodic CE or re-examination. Embracing lifelong learning is key to staying at the top of your game in the ER.

If an ER nurse does advance to become an NP, their scope of practice will depend on state laws. As of 2023, 27 U.S. states and D.C. grant NPs full practice authority, allowing them to diagnose and treat without physician oversight, whereas other states have reduced or restricted practice requiring physician collaboration.

Cost to Become an Emergency Room Nurse

Becoming an ER nurse requires an investment in education, exams, and licensure. Costs can vary widely, but here’s a breakdown of common expenses (with estimates):

- Nursing Degree Tuition: This is the biggest cost. An associate degree in nursing (ADN) at a community college might cost $6,000–$20,000 total for tuition, whereas a Bachelor’s (BSN) program can range from $20,000 (in-state public) to $100,000+ (private) for the full program. Many students offset costs through financial aid, scholarships, or employer tuition reimbursement programs.

- NCLEX-RN Exam & Licensure Fees: The NCLEX exam costs $200 for U.S. candidates. State licensure application fees typically run $50–$200 depending on the state (for example, about $143 in NY). There may also be costs for background checks or fingerprinting (~$50). So budget a few hundred dollars for testing and initial licensing.

- Certification Exams: Specialty certification is optional, but if you pursue it, the CEN exam fee is roughly $370 (discounted to $230 for ENA members). Other cert exams (CPEN, TCRN, etc.) are in a similar range ($300–$400). Study materials or prep courses could add another $50–$200, though many free resources exist.

- License Renewal and CE: RN license renewals often cost around $60–$150 every 1–3 years (varies by state). Continuing education courses can be free or low-cost; many employers offer free CE or reimburse costs. If you purchase CE credits or conference attendance, you might spend $0–$300 per renewal cycle, but savvy nurses take advantage of hospital training and online free CE. Certification renewals (like CEN) may cost a renewal fee (e.g. $170–$250) if not renewed by retaking the exam.

- Miscellaneous: Think about textbooks ($500–$1,000 over the degree), uniforms/supplies ($100–$300), and nursing school fees (lab fees, etc.). Upon hire, some hospitals might require the nurse to take courses like ACLS, which could cost a few hundred dollars – though employers often cover these as a condition of employment. Joining professional organizations (like ENA) has dues (ENA membership is about $115/year), but this can pay off in discounts and resources.

| Expense | Estimated Cost (Low–High) | Additional Tips |

|---|---|---|

| Nursing Degree (ADN vs. BSN) | $6,000 – $100,000+ | Community college ADN programs are cheapest; BSN at public universities is moderate, private schools highest. Tip: Complete prerequisites at a community college or explore accelerated BSN programs if you have a prior degree. Scholarships and loan forgiveness (for working in high-need areas) can significantly offset costs. |

| NCLEX Exam & RN License | $300 – $500 | $200 NCLEX fee + state license application (e.g. $100±) + background check. Tip: NCLEX prep books or courses (~$100) can help ensure you pass on the first try (avoiding re-exam fees). Many find free study groups or use library resources to save money. |

| ER Certification (CEN) | $0 – $400 | CEN exam $370 (non-member) or $230 (ENA member). Tip: Some employers pay for your first attempt if certification is encouraged. Also, ENA membership can save $140 on the exam fee – essentially making membership pay for itself. |

| Licensure Renewal & CE | $50 – $200 per cycle | License renewal fees vary (e.g. $120 biennially). CE costs can be minimal – many free CEU sources online or provided by your hospital. Tip: Use free CE platforms (Medscape, Nurse.com free courses) and attend hospital in-services. If you do conferences for CE, seek employer sponsorship or tax deductions if you itemize. |

| Additional Training Courses | $0 – $300 | Advanced life support courses like ACLS/PALS ($150–$300 each) – often employer-provided. TNCC trauma course (~$300) sometimes covered by hospitals. Tip: Ask your employer about covering these as part of orientation or education benefits. New grads in ER residencies often get these courses free. |

Many hospitals offer tuition reimbursement for nurses who pursue a BSN or specialty certifications while employed. If you start with an ADN, an RN-to-BSN bridge program at a state university or online can be done while working, sometimes with your employer footing part of the bill. Additionally, consider signing up for nursing student loan forgiveness programs (like those for working in underserved areas or through the Public Service Loan Forgiveness for nonprofit hospital employees). These programs can forgive a significant portion of nursing education debt in exchange for a commitment to work in high-need environments – a win-win given ERs in urban or rural underserved areas need skilled nurses. Becoming an ER nurse doesn’t have to break the bank if you plan wisely and take advantage of available resources.

What Emergency Room Nurses Do?

Emergency Room Nurses handle a wide array of critical tasks to ensure patients get timely, lifesaving care. In the hectic environment of an ER, an ER nurse’s roles and responsibilities include:

Triage and Rapid Assessment

ER nurses often serve as triage nurses, the ones who greet incoming patients (or ambulance arrivals) and quickly evaluate their condition. They determine injury/illness severity and prioritize who needs to be seen immediately. For example, a patient with chest pain or not breathing well will be rushed in for treatment before someone with a sprained ankle. This requires sharp assessment skills and the ability to make quick judgments based on limited information.

Direct Patient Care and Procedures

ER nurses provide hands-on care such as starting IV lines, drawing blood for labs, giving medications, and administering treatments like nebulizer breathing treatments or IV fluids. They monitor vital signs frequently (sometimes continuously) and look for changes. ER nurses perform wound care (cleaning and dressing wounds, maybe assisting with sutures or splints), and in some cases assist physicians with minor procedures (for instance, helping reduce a dislocated joint or irrigating a deep cut). They may perform CPR or use a defibrillator if a patient’s heart stops, and they are trained in advanced life support protocols. According to typical ER nurse job descriptions, common duties include everything from taking medical histories and updating electronic health records to helping with diagnostic tests (like getting patients to X-ray/CT scan).

Coordinates Care

ER nurses act as conductors of the multidisciplinary team. They communicate with ER doctors about patient status and critical changes, alert specialists on call (e.g. calling the cardiologist for a heart attack patient or activating the trauma team for a major trauma). They also liaise with lab and radiology departments to chase up test results. If a patient needs admission to the hospital, the ER nurse coordinates the transfer to an inpatient unit; if the patient can go home, the ER nurse preps discharge instructions.

Patient & Family Education and Support

Unlike many other settings, ER nurses often have very limited time with patients, but they still play a an important role in education and emotional support. They explain diagnoses and treatments in simple terms, instruct patients on wound care or medication schedules upon discharge, and counsel families who are anxious and upset. For instance, after stabilizing an asthma attack, an ER nurse might teach the patient how to use an inhaler correctly before discharge. Compassion and communication are key – calming a panicked patient, reassuring a worried parent, or supporting someone who received bad news is all part of an ER nurse’s day.

Multi-Tasking & Crisis Management

An ER nurse might be caring for multiple patients at once, all with different needs. They could be monitoring one patient’s IV drip, while another patient arrives vomiting or seizing in the next bed. ER nurses constantly reprioritize tasks as new patients come and others get discharged. In mass casualty incidents or during community crises, ER nurses may take on disaster triage roles, quickly expanding capacity and working with emergency management protocols. They must thrive under pressure and remain calm and effective during codes (e.g. if a patient “codes” meaning their heart or breathing stops) or when the ER is overflowing. Documentation is also a responsibility – charting assessments, interventions, medications given, and patient responses in the medical record, often on the fly.

One important aspect of an ER nurse’s role is defined by scope of practice, which can vary slightly by state but generally is consistent for RNs across the U.S. Registered Nurses do not independently diagnose conditions or prescribe medication – those actions are reserved for physicians or advanced practice nurses. However, ER RNs do perform nursing assessments and implement physician orders (or standardized protocols). Some states allow experienced RNs to start certain protocols if criteria are met (for example, initiating stroke protocol or giving pain medicine per a standing order set), but they must still work under the oversight of an MD or NP in the ER. By contrast, an Emergency Nurse Practitioner (a type of APRN) can diagnose and prescribe, but only about half the states let NPs do so without physician collaboration. In other states, even NPs have restricted practice and need a physician’s agreement to some extent. The takeaway is that a standard ER nurse (RN) practices as part of a team – they have a lot of responsibility in carrying out critical care, but they operate within the nursing scope defined by their state’s Board of Nursing and hospital policy. They collaborate closely with doctors, who have the ultimate authority on diagnosis and overall treatment plans. This team-based approach ensures patients get comprehensive emergency care.

ER nurses also have to be mindful of legal and ethical considerations. They are mandatory reporters (for suspected abuse, etc.), they must ensure informed consent is obtained for procedures, and they often act as patient advocates in fast-moving situations. For example, if a patient is in severe pain, the ER nurse voices that to the physician and requests timely pain management. They also adhere to EMTALA regulations (which ensure everyone is treated in an emergency regardless of ability to pay or other factors). In all, the ER nurse’s role is incredibly broad – part caregiver, part coordinator, part problem-solver – and it’s central to the functioning of an emergency department.

Salary & Job Outlook

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), there were about 3.3 million registered nursing jobs in 2023, and employment is projected to grow 6% from 2023 to 2033. This rise in demand is driven by an aging population and the prevalence of chronic conditions – more patients require complex emergency care than ever before. ER nursing offers job stability and growth in the coming decade, as hospitals and trauma centers expand emergency services to meet these needs. If you’re an aspiring nurse or a current RN considering advancement, read on to see if the exciting world of emergency nursing is your calling.

Salary

Emergency room nurses are in demand nationwide, and their salaries reflect both the critical nature of their work and regional cost-of-living differences. Since ER nurses are RNs, their pay falls within the range of registered nurse salaries, often with a premium for specialty experience or certifications. According to the latest BLS data, the median annual salary for registered nurses is $93,600 (as of May 2024). This median covers RNs across all specialties. ER nurses in particular may earn closer to or above the median, especially if they work night shifts (which often include shift differentials) or in high-cost urban areas.

To give a snapshot of how RN salaries (including ER nurses) vary by state, below is a mini salary table for five example states around the U.S. All figures are median annual RN salaries (which assume full-time employment):

| State | Median RN Salary |

|---|---|

| California | $140,330 |

| New York | $105,600 |

| Texas | $90,010 |

| Florida | $82,850 |

| Alabama | $71,040 |

As the table shows, an ER nurse in California (the highest-paying state for RNs) has a median salary nearly double that of an ER nurse in Alabama on average. Large metro areas and states with higher living costs tend to pay more – for instance, New York and California ER nurses command six-figure salaries on average, whereas in many Southern states the median is in the $70k–$80k range. Keep in mind these are median figures; experienced ER nurses, especially those with a BSN, CEN certification, or who take on charge nurse roles, can earn more. The top 10% of RNs nationally earn over $135,000, which often includes nurses in high-paying specialties like critical care or those who work substantial overtime.

Aside from base pay, ER nurses often have opportunities for overtime (ERs run 24/7 and frequently need extra shifts covered) and shift differentials (extra pay for evenings, nights, weekends). Many hospitals also offer retention bonuses or hazard pay during times of extreme demand (for example, during the COVID-19 surges, some ER nurses received bonus pay). Travel nursing is another avenue – experienced ER nurses sometimes work as travel RNs, taking 13-week contracts in different states, which can pay a higher weekly rate (though typically without long-term benefits).

Job Outlook

The career prospects for ER nurses are strong. BLS projects a 6% growth in RN employment from 2023 to 2033, which translates to roughly 195,000 new RN positions nationwide. Specifically within that, emergency nursing roles are expected to grow in number because emergency departments are seeing higher volumes (due to population growth, aging populations, and periods of public health crises). The BLS also notes about 194,500 RN job openings each year on average, when accounting for turnover and retiring nurses. A significant portion of those openings are in hospitals – and ERs are a core hospital service.

Demand is rising particularly for ER nurses in rural areas (where shortages of healthcare professionals persist) and in inner-city hospitals (which often see high patient volumes in the ER). Additionally, urgent care centers and freestanding emergency clinics have proliferated across the U.S., creating alternative emergency nursing jobs outside of traditional hospital ERs. While these may not handle major traumas, they do need skilled nurses for triage and acute care – expanding the job market for emergency nurses.

Why the optimistic outlook? It comes down to demographics and healthcare trends: an aging population means more emergencies like heart attacks and strokes; increased prevalence of chronic illnesses like diabetes means more complications that can land patients in the ER. Furthermore, as many current nurses retire (the median age of RNs is early 50s), replacement needs are high. The American Nurses Association highlights that each year a large cohort of nurses leave the workforce, and more are needed to fill the gap – emergency nursing included.

One more factor: public health emergencies and pandemics have underscored the importance of emergency care. The COVID-19 pandemic, for example, pushed ERs to the limit and created awareness of the need for robust emergency nursing staff. In response, many hospitals have invested in hiring and training more ER nurses, and some governments provided funding for emergency department expansions. ER nurses proved indispensable in crises, and that has elevated the profile (and negotiating power) of this specialty.

If you become an ER nurse, you can expect competitive pay – often above the national RN median in many locales – and a positive job outlook with diverse opportunities across the country. Whether you choose a high-energy urban trauma center or a smaller community ER, your skills will be in demand.

Specializations & Subspecialties in Emergency Nursing

Emergency nursing in itself is a specialty, but ER nurses can further focus on particular areas of emergency care. Many develop subspecialties or advanced roles based on patient population, setting, or type of emergency. Here are some major specializations and subspecialty paths for ER nurses:

Trauma Nursing

Trauma nurses specialize in caring for patients with severe injuries (e.g. from car accidents, falls, gunshots). Often working in Level I or II Trauma Centers, they are experts in rapid assessment of injuries and coordinating massive transfusions, emergency surgeries, etc. Trauma nurses usually take the Trauma Nursing Core Course (TNCC) and may become a Trauma Certified Registered Nurse (TCRN). They work in trauma bays of ERs or on trauma resuscitation teams.

Pediatric Emergency Nursing

These nurses focus on emergencies in infants, children, and teens. Pediatric ER nurses work in children’s hospital ERs or pediatric-specific sections of general ERs. They need knowledge of pediatric vital signs, medication dosages, and communication techniques for kids. Emergency Nursing Pediatric Course (ENPC) is common, and they might earn the Certified Pediatric Emergency Nurse (CPEN) credential. This subspecialty is great for nurses who love kids and can handle the emotional challenges of pediatric trauma/illness.

Flight Nurse / Transport Nurse

Flight nurses provide critical care transport for patients via helicopter or airplane (and similarly, ground transport nurses ride in ambulances for critical-care transfers). They handle unstable patients being rushed to trauma centers or being moved between facilities. These nurses must work virtually alone with their transport team, often initiating life-saving interventions in air or on the road. Many have ICU or ER backgrounds. Certifications like Certified Flight Registered Nurse (CFRN) or Certified Transport RN (CTRN) are offered by BCEN. They also require training in aeromedical physiology and may need to learn additional skills (like managing ventilators or balloon pumps during transport). It’s a high-adrenaline role suited to very autonomous nurses.

Emergency Nurse Practitioner (ENP)

This is an advanced practice role where a nurse becomes a licensed Nurse Practitioner with a focus in emergency medicine. ENPs can examine, diagnose, and manage patients in the ER much like a physician would (often handling the fast-track or lower-acuity patients, or working alongside doctors in main ER for more serious cases). To become an ENP, a nurse must complete an NP program (usually Family NP or Acute Care NP) and then often pursue a post-master’s Emergency NP certificate or fellowship. They can also obtain ENP-C certification through the AANP (available to FNPs who meet emergency specialty criteria). ENPs have varying authority based on state law – in some states they practice independently, in others they must have a physician agreement. This path is ideal for nurses who want greater autonomy and a provider role in emergency settings.

Emergency/Trauma Clinical Nurse Specialist (CNS)

A CNS in emergency/trauma is an advanced clinician who focuses on improving emergency care through education, policy, and quality improvement. They might develop ER protocols, train staff on new procedures, and lead performance improvement projects (like reducing wait times or improving sepsis outcomes). This role requires a Master’s (or Doctorate) as a CNS with an emergency specialization. CNSs don’t typically take primary patient assignments; they serve as expert resources for the nursing staff and ensure evidence-based practices are implemented. It’s a more behind-the-scenes but influential specialization.

Additionally, ER nurses can specialize in niches like toxicology (poison control) – working with poison control centers to guide treatment of overdoses or ingestions – or disaster response, joining disaster medical assistance teams (DMATs) that deploy to emergencies like hurricanes or mass casualty events. Some may focus on geriatric emergency nursing, recognizing and managing emergencies in older adults with frailty considerations, or psychiatric emergencies, mastering skills to care for patients in mental health crisis in the ER.

Below is a summary chart of a few ER nursing subspecialties and their focus:

| Subspecialty | Focus & Role | Practice Settings | Extra Training/Certifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trauma Nurse | Cares for patients with critical injuries (e.g. multi-system trauma). Manages immediate resuscitation and stabilization of trauma victims. | Level I/II Trauma Center ERs, trauma resuscitation units, shock/trauma ICU (some cross-train). | TNCC course; TCRN certification (Trauma Certified RN); ATLS (for MDs, but nurses learn concepts). |

| Pediatric ER Nurse | Specializes in emergency care for children (from infants to adolescents). Uses child-specific assessment and communication. Handles issues like pediatric respiratory emergencies, fevers, seizures, injuries. | Children’s hospitals emergency departments; pediatric urgent care; general ER with dedicated peds section. | ENPC (Emergency Nursing Pediatric Course); CPEN certification (Certified Pediatric Emergency Nurse); PALS (Pediatric Advanced Life Support). |

| Flight/Transport Nurse | Provides critical care during air or ground transport. Autonomously manages drips, airways, and monitors en route. Prepared for in-transit emergencies (e.g. patient deteriorating mid-flight). | Air ambulance services (Life Flight, etc.); Critical care transport teams (ambulance). Often affiliated with trauma centers or large hospitals. | Experience (often 3–5+ years ICU/ER); CFRN (Certified Flight RN) or CTRN (Certified Transport RN); Advanced trauma life support concepts; may require EMT certification in some programs. |

| Emergency Nurse Practitioner (ENP) | Functions as a nurse practitioner in the ER, evaluating and treating patients, ordering tests, and prescribing meds. Often handles lower acuity cases or fast-track, but can manage higher acuity with physician collaboration. | Hospital emergency departments; Urgent care clinics; Freestanding ERs (where they might serve as the primary provider on duty); Rural ERs (to extend coverage where physician supply is low). | MSN or DNP in NP (usually FNP or AG-ACNP track); ENP-BC or ENP-C specialty certification (via ANCC or AANP) after establishing NP experience in emergency settings; ongoing state NP licensure. |

| Emergency CNS (Clinical Nurse Specialist) | Expert clinician/consultant improving emergency nursing practices. Develops policies, leads training and quality initiatives, and may assist with complex cases. | Large hospital systems (ER department leadership teams); Trauma centers (to coordinate trauma program); Academic medical centers (blending research and practice improvements). | MSN/DNP as Clinical Nurse Specialist with emergency/trauma focus; CNS board certification (some states require CNS license); often also holds CEN or TCRN to validate clinical expertise. |

It’s worth noting that many ER nurses start as generalists in the emergency department and naturally grow into these subspecialty roles through on-the-job experience. For example, a nurse might work several years in a busy ER, develop a passion for trauma cases, and then become the unit’s trauma coordinator or get certified in trauma nursing. The field of emergency nursing is broad, and there’s plenty of room to find your niche if you desire.

Professional Organizations & Resources

Joining professional organizations can greatly benefit an ER nurse’s career through networking, education, and advocacy. Below are key organizations and resources for emergency nurses (and nurses in general), along with their mission and member benefits:

| Organization — Who They Serve | Membership/Reach | Primary Mission | Member Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| American Nurses Association (ANA) – National professional organization for all RNs | Represents ~4 million RNs across the U.S. (members in every state). (Membership is voluntary; tens of thousands of nurses are dues-paying members, and ANA represents the broader RN workforce through state nursing associations.) | To advance the nursing profession and advocate for nurses’ interests. ANA sets high standards of nursing practice, promotes safe and ethical work environments, and influences health policy. Essentially, it’s the strong unified voice of nursing on national issues. | Advocacy: Lobbying at federal level for nursing issues (e.g. safe staffing, scope of practice). Professional development: webinars, online CE courses (many free for members), journals like American Nurse. Networking: Access to ANA’s online communities and local state chapters. Resources and Discounts: Career center, conferences, certification discounts (ANA members often get reduced fees for ANCC certification exams), insurance deals, etc.. |

| Emergency Nurses Association (ENA) – Specialty org for emergency nursing | ~50,000 members worldwide (primarily U.S.), representing emergency nurses in all 50 states and 35 countries. | Dedicated to advancing emergency nursing practice and excellence in emergency care. ENA addresses ER-specific issues, develops evidence-based guidelines, and provides education tailored to emergency nurses. It also advocates for emergency healthcare improvements (like injury prevention, better ER policies). | Education: ENA offers ENA University with courses, webinars, and the renowned Emergency Nursing Conference (annual meeting) for skill-building. Publishes the Journal of Emergency Nursing (free subscription for members). Certification support: ENA members get discounts on the CEN exam and review materials. Networking: Local ENA chapters provide networking, support, and mentorship at the state level. Advocacy: ENA advocates for issues like workplace violence prevention in ERs and trauma system funding. Members can join committees or volunteer for injury prevention programs. |

| American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN) – Specialty org for acute and critical care nurses (covers ICU and also ER to an extent) | Over 130,000 members (one of the largest nursing specialty orgs in the U.S.). Includes ICU, telemetry, and many ER nurses interested in critical care topics. | To advance acute and critical care nursing through education, research, and advocacy. AACN’s vision is creating a healthcare system driven by the needs of critically ill patients and families, with nurses making optimal contributions. | Certification & Education: AACN administers certifications like CCRN (for ICU) – not ER-specific, but many concepts overlap. They provide a wealth of online CE, an annual conference (NTI – National Teaching Institute) which includes some emergency/trauma sessions, and publications like Critical Care Nurse. Practice Resources: evidence-based protocols, research grants. Community: Local chapters and an online discussion platform for members to share best practices. While AACN isn’t focused solely on ER, ER nurses benefit from membership if they want to deepen critical care skills or move between ER and ICU settings. |

| American Association of Nurse Practitioners (AANP) – National organization for NPs of all specialties (including emergency NPs) | 121,000+ members, representing the interests of over 430,000 licensed NPs in the U.S.. (AANP is the largest NP organization.) | To empower nurse practitioners and champion high-quality, accessible health care. AANP’s mission includes supporting NPs in practice, education, advocacy, research, and leadership. It is the leading voice pushing for full practice authority for NPs nationwide. | Advocacy: Strong lobbying for NP-friendly laws (like expanding scope of practice). Educational Resources: Free CE opportunities, clinical practice tools, and specialty practice groups (they have an Emergency NP specialty interest group for ENPs to network). Conferences: AANP hosts national and regional conferences with sessions for various NP tracks (including emergency care updates). Publications: Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, policy briefs, etc. Career support: Job boards for NP positions, mentoring programs. For an ER nurse considering or who has become an NP, AANP is a key resource, and even as an RN it’s good to know how this organization is shaping the role of advanced practice in emergency settings. |

| Society of Trauma Nurses (STN) – Professional organization for trauma nursing across the continuum | Membership includes trauma program managers, trauma coordinators, ED and ICU trauma nurses, and trauma advanced practice nurses worldwide. (Hundreds of hospitals are represented; STN is smaller than ENA, but very focused.) | To ensure optimal trauma care for all patients through initiatives in trauma education, prevention, and collaboration. STN focuses on improving trauma systems and the nursing care of trauma patients, from prehospital to rehab. | Education: STN offers TraumaCon (annual conference), online courses like the Trauma Care curriculum, and publications like the Journal of Trauma Nursing. They developed the ATCN (Advanced Trauma Care for Nurses) course, which parallels the physicians’ ATLS course for trauma assessment. Networking & Leadership: STN connects trauma nurse leaders globally, providing mentorship and leadership development (e.g. a Leadership Institute course). Resources: Best practice guidelines for trauma care, injury prevention program support, and research grants. ER nurses involved in trauma programs or seeking to specialize in trauma will find STN membership valuable for staying at the forefront of trauma care improvements. |

These organizations provide a support system for ER nurses and help you stay current in the field. For example, through ENA you might access a clinical practice guideline on sepsis in the ER, or via ANA you might join a committee on safe staffing. Professional bodies also often offer scholarships and certification discounts, as well as forums to voice your concerns (like advocating against workplace violence, which has been a notable issue in ER settings).

Beyond formal organizations, ER nurses often leverage online communities and resources such as r/Nursing or r/EmergencyNursing on Reddit, various Facebook groups for ER nurses, and journals like Emergency Medicine Journal or Annals of Emergency Medicine (for more physician-oriented perspective, but useful for learning). However, be cautious to vet information; official organizations like ENA or ANA provide validated, evidence-based resources which are crucial in a specialty where guidelines (e.g., for advanced cardiac life support) update frequently.

By engaging with professional organizations, an ER nurse gains a community of peers, opportunities for continuing education, and a platform to influence the future of emergency care. It’s highly recommended to join at least one – most ER nurses become ENA members early in their career to start reaping these benefits.

Skills & Qualities for Success

Succeeding as an Emergency Room Nurse requires a mix of technical proficiency and soft skills. Here are some essential skills and qualities that top ER nurses possess:

Rapid Critical Thinking and Decision-Making

The ability to quickly assess a situation, prioritize needs, and make sound decisions is vital. ER nurses often have mere seconds to recognize a life-threatening condition and act (for example, identifying signs of a stroke or sepsis and initiating protocol immediately).

Multitasking and Time Management

Emergency nurses juggle multiple patients and tasks efficiently. They might start an IV on one patient while monitoring another’s cardiac rhythm and simultaneously answering a physician’s question about a third patient. Staying organized under chaos and thriving under pressure are key qualities.

Strong Clinical Skills

Breadth of knowledge is crucial – ER nurses need to be skilled in IV insertion, medication administration (covering dozens of emergency drugs), wound suturing or dressing, operating equipment like defibrillators or ventilators, and performing CPR/intubation assist, to name a few. Being technologically savvy with monitors, pumps, and electronic records is also important.

Communication and Teamwork

ERs are a team sport. Nurses must communicate clearly with physicians (“Here’s the patient’s BP, I’ve given 2 liters IV fluids, awaiting lab results”), with technicians, paramedics, and with patients/families. They also need to collaborate seamlessly – handing off tasks, asking for help, and coordinating during resuscitations. Good ER nurses also translate medical jargon into plain language for patients and keep families informed to reduce their anxiety.

Emotional Resilience and Compassion

ER nursing can be emotionally intense – you’ll witness trauma, severe illness, and sometimes death. A successful ER nurse has empathy for patients’ suffering but can also maintain composure and focus. They must process stress and grief in healthy ways (often through peer support) to avoid burnout. Being able to stay calm and provide reassurance to patients and families during crises is a hallmark of a great ER nurse.

Adaptability and Flexibility

Every shift in the ER is different. Nurses might float between triage, trauma, and general treatment areas as needed. A positive, adaptable attitude – being willing to jump in wherever there’s a critical need – makes one indispensable. Flexibility also extends to schedule (ER nurses often rotate nights, weekends, holidays) and being able to pivot when protocols or situations change unexpectedly.

Attention to Detail

From double-checking medication dosages to catching a subtle change in a patient’s condition, detail-oriented care saves lives. Even amidst commotion, ER nurses must carefully document, avoid errors, and adhere to safety checks (like patient identification, allergy verification) consistently.

Physical Stamina

Emergency nursing is physically demanding. You’ll be on your feet nearly the entire shift, lift or turn patients, perform CPR (which is physically strenuous), and run around a lot. Good ER nurses have stamina and also know how to take quick breaks or stay hydrated to keep going strong. Having a degree of fitness and a pair of comfortable shoes goes a long way.

Advocacy and Confidence

ER nurses advocate for their patients. This could mean assertively suggesting to the doctor that a patient appears to be deteriorating and needs immediate attention, or refusing to discharge someone if they feel the patient isn’t stable yet. A successful ER nurse is confident in their knowledge and speaks up to ensure safe, appropriate care.

These skills develop over time – no one walks into their first emergency shift a master of all. However, cultivating these qualities will significantly enhance your effectiveness and satisfaction in the ER role. Many emergency nurses say that quick thinking, team spirit, and a cool head under pressure are the most important traits for the job. The good news is, working in the ER will sharpen these skills quickly. Every shift is practice in multitasking, critical thinking, and compassionate care, so you’ll find yourself growing into the role with each experience.

Pros & Cons of an Emergency Room Nurse Career

Every nursing specialty has its ups and downs. Emergency nursing is extremely rewarding, but it also comes with challenges not every nurse is up for. Here’s a balanced look at pros and cons of a career as an ER nurse:

Pros of an ER Nurse

- Meaningful, Life-Saving Impact: ER nurses make a tangible difference every day. From reviving a coding patient to calming a frightened child with a broken arm, the work is often truly life-saving and meaningful. Many ER nurses report high job satisfaction knowing they helped people in their most critical moments.

- Dynamic, Fast-Paced Environment: Boredom is rarely an issue in the ER. No two shifts are the same – each day brings new cases and challenges. This variety means constant learning and keeps the work engaging. If you thrive on adrenaline and excitement, the ER is full of it (“adrenaline-inducing moments keep the job from ever being too boring”).

- Strong Camaraderie and Teamwork: ER teams are known to be tight-knit. Handling crises together forges deep bonds among nurses, doctors, techs, and paramedics. The teamwork-oriented environment is a big plus – you’re never alone in a tough situation, and colleagues support each other like family.

- Wide-Ranging Skills Development: Working in an ER will make you a very well-rounded nurse. You gain experience with all ages and all medical disciplines (cardiac, ortho, neuro, trauma, psych, etc.). This broad skill set can open doors to other specialties or advanced practice roles. Many nurses say no other job gives you such a wide scope of practice and learning opportunities so quickly.

- Good Earning Potential & Demand: ER nurses often have opportunities for extra income through shift differentials, overtime, or travel assignments. The high demand for ER skills means you have job security and flexibility to work anywhere in the country. It’s satisfying to be in a role that is both valued and rewarded in the healthcare system.

Cons of an ER Nurse

- High Stress & Pressure: ER nursing is inherently stressful. You’re dealing with life-and-death situations under time constraints, which can be exhausting. The constant influx of patients and noise and urgency can lead to burnout if not managed. Even the most calm nurses can feel overwhelmed at times by the high-stress environment.

- Emotional Toll: Seeing trauma victims, critically ill patients, or deceased patients (including children) can be emotionally taxing. ER nurses regularly witness grief and sometimes experience patient loss despite their best efforts. Compassion fatigue is a real risk – you have to find ways to cope with the emotional impact (debriefing with colleagues, counseling, etc.) to maintain your mental health.

- Irregular Hours & Physical Demands: Most ERs operate 24/7, which means shift work. Night shifts, weekends, and holidays are part of the job. Constant rotation or long 12-hour shifts can disrupt your sleep and personal life. Additionally, the job is physically tough – lots of standing, lifting, and fast-paced activity without many breaks. This can be draining and lead to aches or injuries over time if not careful.

- Exposure to Workplace Hazards: ER nurses face higher exposure to certain risks – workplace violence from unruly patients or visitors is a serious concern, as ERs often see individuals under the influence or in mental crisis. There’s also exposure to infectious diseases (e.g. treating patients with flu, COVID-19, etc.) and hazardous substances. Strict safety protocols exist, but the risk is never zero.

- Crowding and Resource Strains: Emergency departments can get overcrowded especially during flu season or a local crisis. ER nurses must manage with sometimes limited resources or staff. Treating patients in hallways, or juggling too many cases at once, can be frustrating and feel like you can’t give optimal care. Dealing with hospital capacity issues and occasional lack of beds is an ongoing challenge in many ERs.

- Documentation & Legal Pressure: Charting every detail in real-time while managing emergencies is difficult, yet crucial for legal and continuity reasons. There’s pressure to document thoroughly in case of lawsuits (ERs are a high liability area). The combination of high accountability and the chaotic environment can be stressful – one must constantly be on their toes to avoid mistakes.

Despite the challenges, many ER nurses say they couldn’t imagine doing anything else. The adrenaline, the gratification of saving lives, and the solidarity among the ER team often outweigh the negatives for those who choose this career. However, it’s important to acknowledge the cons and develop strategies (self-care, mentorship, stress management techniques) to mitigate them.

Ready to Become an Emergency Nurse?

A career as an emergency room nurse in the U.S. offers a unique mix of rewards and challenges. On the one hand, it’s one of the most impactful and dynamic roles in nursing – you’re literally saving lives and never stop learning. ER nurses enjoy strong demand, solid salaries, and the camaraderie of working in a high-functioning team. On the other hand, the job can be intense: long shifts, emotional extremes, and high-pressure situations are all in a day’s work. Success in this field means mastering not only clinical skills but also stress management and compassionate communication.

In the end, emergency nursing is more than just a job; it’s a mindset. It’s about expecting the unexpected, staying calm amid chaos, and finding fulfillment in helping others on what might be the worst day of their lives. Many ER nurses will tell you that despite the hardships, the moments of triumph – seeing a critical patient turn the corner, or comforting a family with empathy – make it all worth it.

If you’re considering this path, reflect on what drives you. Do you thrive in fast-paced environments and want to make a difference when it matters most? If yes, the ER might just be the perfect stage for your nursing career. With preparation, dedication, and a bit of courage, you could soon find yourself saying, “I can’t imagine being anything other than an emergency room nurse.” So, can you see yourself in the ER scrubs, ready for whatever comes through those hospital doors?

Leave a Comment