Learn about the nursing care management of patients with burn injury in this nursing study guide.

Table of Contents

- What is Burn Injury?

- Classification

- Pathophysiology

- Statistics and Epidemiology

- Clinical Manifestations

- Prevention

- Complications

- Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

- Medical Management

- Nursing Management

- Practice Quiz: Burn Injury

- See Also

What is Burn Injury?

A nurse who cares for a patient with burn injury should be knowledgeable about the physiologic changes that occur after a burn, as well as astute assessment skills to detect subtle changes in the patient’s condition.

- Burn injury is the result of heat transfer from one site to another.

- Burns disrupt the skin, which leads to increased fluid loss; infection; hypothermia; scarring; compromised immunity; and changes in function, appearance, and body image.

- Young children and the elderly continue to have increased morbidity and mortality when compared to other age groups with similar injuries. Inhalation injuries in addition to cutaneous burns worsen the prognosis.

- The severity of each burn is determined by multiple factors that when assessed help the burn team estimate the likelihood that a patient will survive and plan for the care for each patient.

Classification

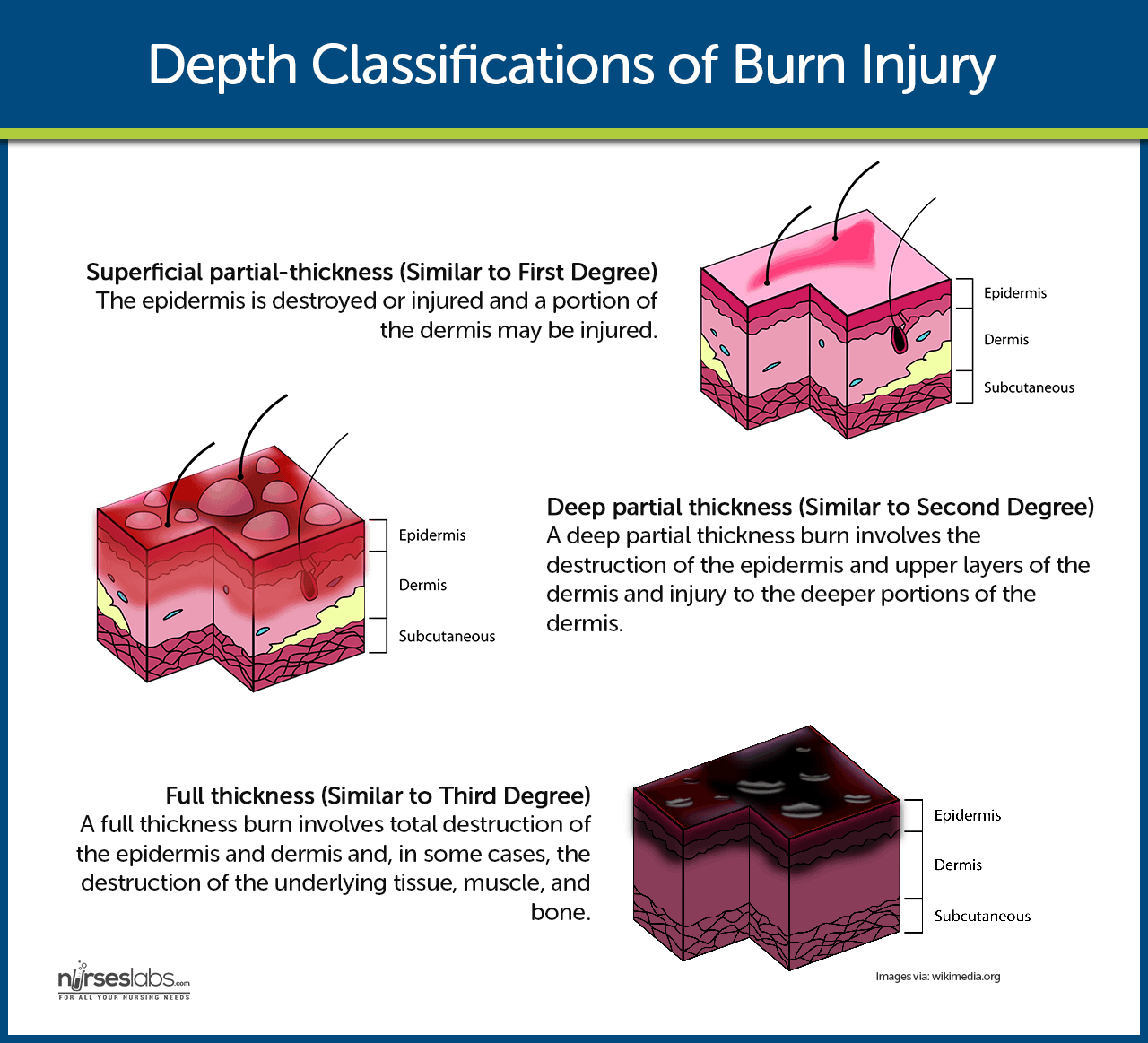

Burns are classified according to the depth of tissue destruction as superficial partial-thickness injuries, deep partial-thickness injuries, or full-thickness injuries.

- Superficial partial-thickness. The epidermis is destroyed or injured and a portion of the dermis may be injured.

- Deep partial-thickness. A deep partial-thickness burn involves the destruction of the epidermis and upper layers of the dermis and injury to the deeper portions of the dermis.

- Full-thickness. A full-thickness burn involves total destruction of the epidermis and dermis and, in some cases, the destruction of the underlying tissue, muscle, and bone.

Pathophysiology

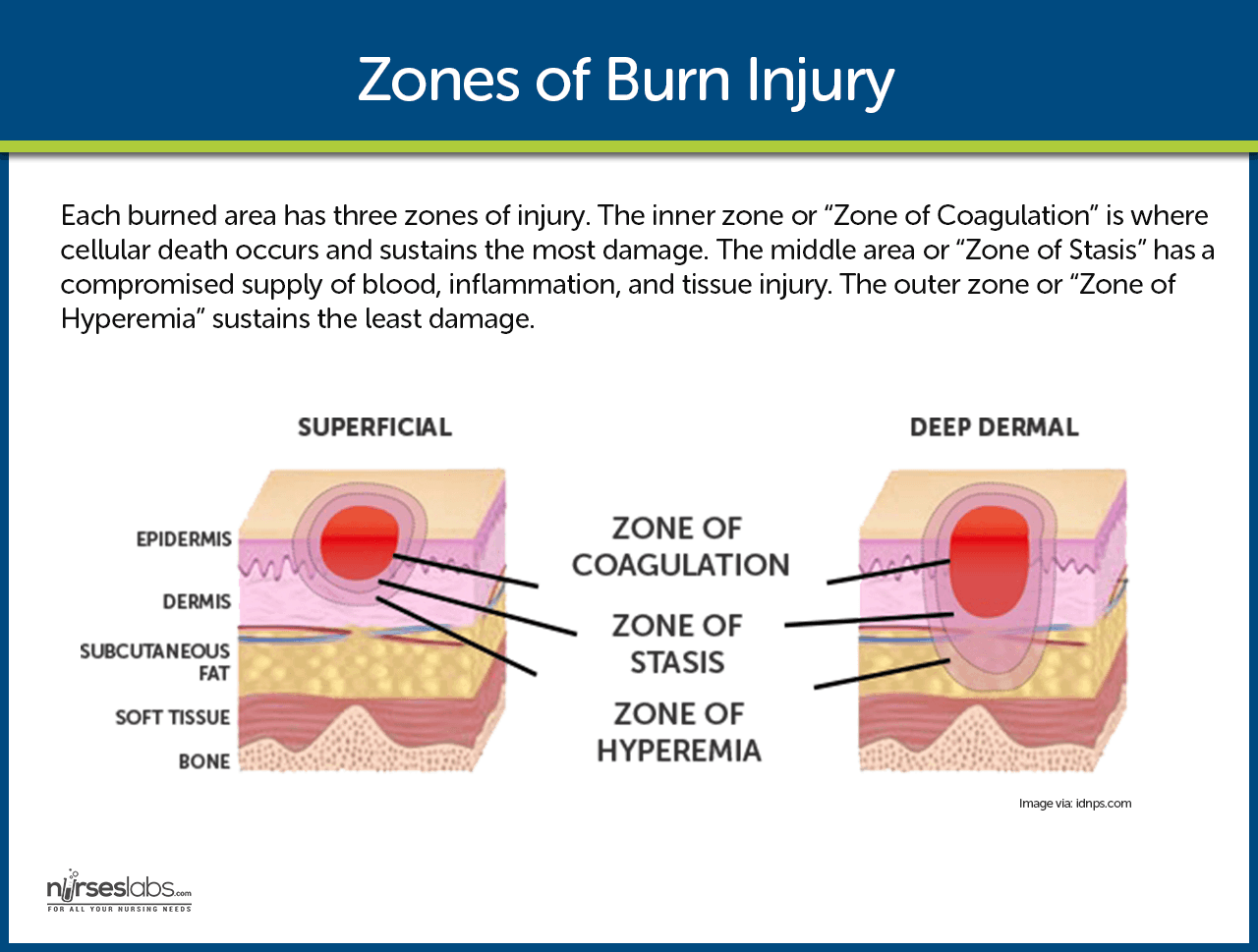

Tissue destruction results from coagulation, protein denaturation, or ionization of cellular components.

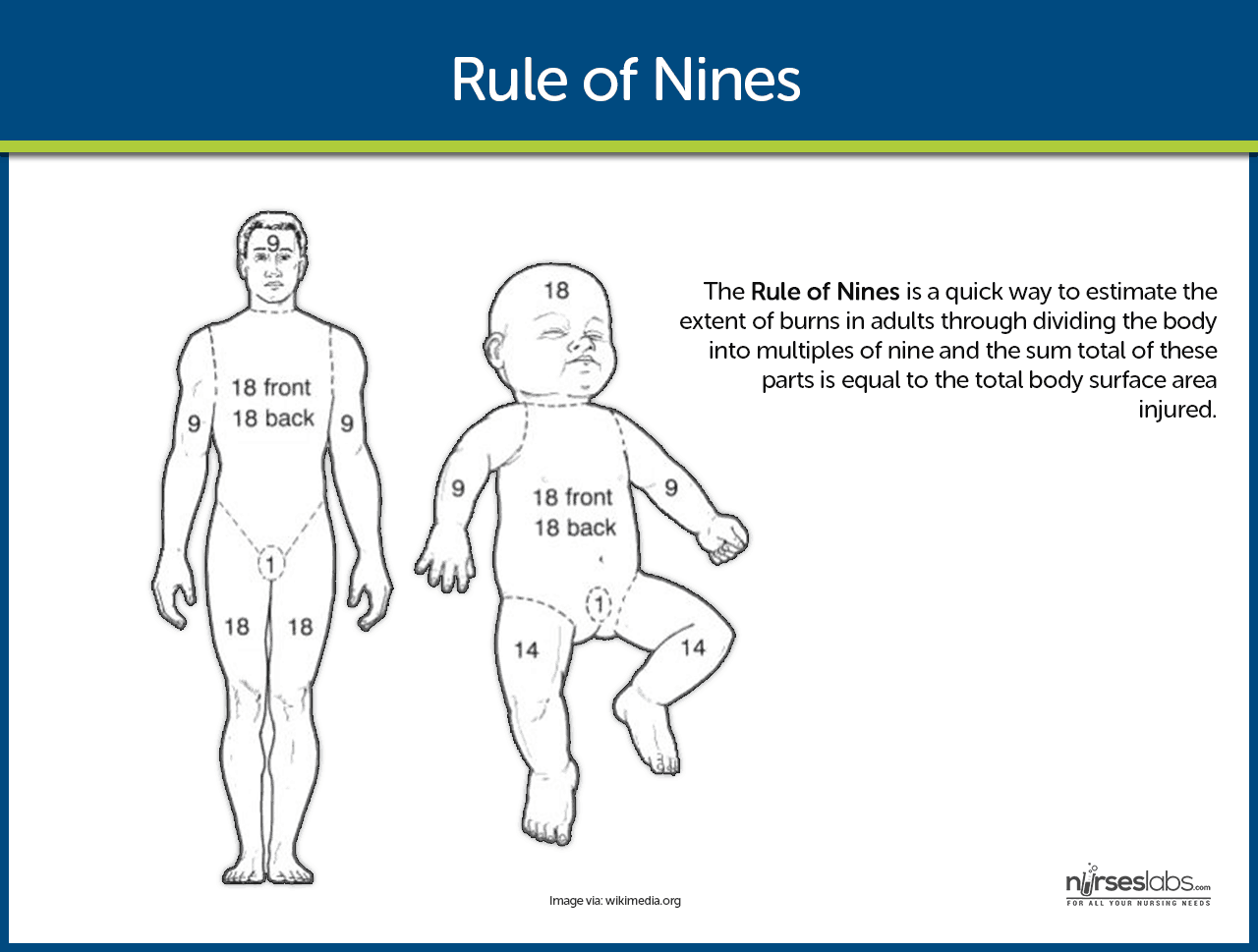

- Local response. Burns that do not exceed 20% of TBSA according to the Rule of Nines produces a local response.

- Systemic response. Burns that exceed 20% of TBSA according to the Rule of Nines produces a systemic response.

- The systemic response is caused by the release of cytokines and other mediators into the systemic circulation.

- The release of local mediators and changes in blood flow, tissue edema, and infection, can cause the progression of the burn injury.

Statistics and Epidemiology

A burn injury can affect people of all age groups, in all socioeconomic groups.

- An estimated 500, 000 people are treated for minor burn injury annually.

- The number of patients who are hospitalized every year with burn injuries is more than 40, 000, including 25, 000 people who require hospitalization in specialized burn centers across the country.

- The remaining 5, 000 hospitals see an average of three burns per year.

- Of those people admitted in burn centers, , 47% of their injuries occurred at home, 27% on the road, 8% are occupational, 5% are recreational, and the remaining 13% from other sources.

- 40% of these injuries are flame related, 30% scald injuries, 4% electrical, 3% chemical, and the remaining unspecified.

- Males have greater than twice the chance of burn injury than women.

- The most frequent age group for contact burns is between 20 to 40 years of age.

- The National Fire Protection Association reports 4, 000 fire and burn deaths each year.

- Of the 4,000, 3, 500 deaths occur from residential fires and the remaining 500 from other sources such as motor vehicle crashes, scalds, or electrical and chemical sources.

- The overall mortality rate, for all ages and for total body surface area burned is 4.9%.

Clinical Manifestations

The changes that occur in burns include the following:

- Hypovolemia. This is the immediate consequence of fluid loss and results in decreased perfusion and oxygen delivery.

- Decreased cardiac output. Cardiac output decreases before any significant change in blood volume is evident.

- Edema. Edema forms rapidly after burn injury.

- Decreased circulating blood volume. Circulating blood volume decreases dramatically during burn shock.

- Hyponatremia. Hyponatremia is common during the first week of the acute phase, as water shifts from the interstitial space to the vascular space.

- Hyperkalemia. Immediately after burn injury hyperkalemia results from massive cell destruction.

- Hypothermia. Loss of skin results in an inability to regulate body temperature.

Prevention

To promote safety and avoid burns, the following must be done to prevent burns:

- Advise that matches and lighters be kept out of reach of children.

- Emphasize the importance of never leaving children unattended around fire or in bathroom/bathtub.

- Caution against smoking in bed, while using home oxygen, or against falling asleep while smoking.

- Caution against throwing flammable liquids onto an already burning fire.

- Caution against using flammable liquids to start fires.

- Recommend avoidance of overhead electrical wires and underground wires when working outside.

- Advise that hot irons and curling irons be kept out of reach of children.

- Caution against running an electrical cord under carpets or rugs.

- Advocate caution when cooking, being aware of loose clothing hanging over the stove top.

- Recommend having a working fire extinguisher in the home and knowing how to use it.

Complications

There are a lot of consequences involved in burn injuries that may progress without treatment.

- Ischemia. As edema increases, pressure on small blood vessels and nerves in the distal extremities causes an obstruction of blood flow.

- Tissue hypoxia. Tissue hypoxia is the result of carbon monoxide inhalation.

- Respiratory failure. Pulmonary complications are secondary to inhalational injuries.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

Various methods are used to determine the TBSA affected by burns.

- Rule of Nines. A common method, the rule of nines is a quick way to estimate the extent of burns in adults through dividing the body into multiples of nine and the sum total of these parts is equal to the total body surface area injured.

- Lund and Browder Method. This method recognizes the percentage of surface area of various anatomic parts, especially the head and the legs, as it relates to the age of the patient.

- Palmer Method. The size of the patient’s palm, not including the surface area of the digits, is approximately 1% of the TBSA, and the patient’s palm without the fingers is equivalent to 0.5% TBSA and serves as a general measurement for all age groups.

Medical Management

Burn care is a delicate task any nurse can have and being knowledgeable in the proper sequencing of the interventions is very essential.

- Transport. The hospital and the physician are alerted that the patient is en route so that life-saving measures can be initiated immediately.

- Priorities. Initial priorities in the ED remain airway, breathing, and circulation.

- Airway. 100% humidified oxygen is administered and the patient is encouraged to cough so that secretions can be removed by coughing.

- Chemical burns. All clothing and jewelry are removed and chemical burns should be flushed.

- Intravenous access. A large bore (16 or 18 gauge) IV catheter is inserted in the non-burned area.

- Gastrointestinal access. If the burn exceeds 20% to 25% TBSA, a nasogastric tube is inserted and connected to low intermittent suction because there are patients with large burns that become nauseated.

- Clean beddings. Clean sheets are placed over and under the patient to protect the burn wound from contamination, maintain body temperature, and reduce pain caused by air currents passing over exposed nerve endings.

- Fluid replacement therapy. The total volume and rate of IV fluid replacement is gauged by the patient’s response and guided by the resuscitation formula.

Nursing Management

Nursing management in burn care requires specific knowledge on burns so that there could be a provision of appropriate and effective interventions.

Nursing Assessment

The nursing assessment focuses on the major priorities for any trauma patient; the burn wound is a secondary consideration.

- Focus on the major priorities of any trauma patient. the burn wound is a secondary consideration, although aseptic management of the burn wounds and invasive lines continues.

- Assess circumstances surrounding the injury. Time of injury, mechanism of burn, whether the burn occurred in a closed space, the possibility of inhalation of noxious chemicals, and any related trauma.

- Monitor vital signs frequently. Monitor respiratory status closely; and evaluate apical, carotid, and femoral pulses particularly in areas of circumferential burn injury to an extremity.

- Start cardiac monitoring if indicated. If patient has history of cardiac or respiratory problems, electrical injury.

- Check peripheral pulses on burned extremities hourly; use Doppler as needed.

- Monitor fluid intake (IV fluids) and output (urinary catheter) and measure hourly. Note amount of urine obtained when catheter is inserted (indicates preburn renal function and fluid status).

- Obtain history. Assess body temperature, body weight, history of preburn weight, allergies, tetanus immunization, past medical surgical problems, current illnesses, and use of medications.

- Arrange for patients with facial burns to be assessed for corneal injury.

- Continue to assess the extent of the burn; assess depth of wound, and identify areas of full and partial thickness injury.

- Assess neurologic status: consciousness, psychological status, pain and anxiety levels, and behavior.

- Assess patient’s and family’s understanding of injury and treatment. Assess patient’s support system and coping skills.

Acute Phase

The acute or intermediate phase begins 48 to 72 hours after the burn injury. Burn wound care and pain control are priorities at this stage.

Acute or intermediate phase begins 48 to 72 hours after the burn injury.

- Focus on hemodynamic alterations, wound healing, pain and psychosocial responses, and early detection of complications.

- Measure vital signs frequently. Respiratory and fluid status remains highest priority.

- Assess peripheral pulses frequently for first few days after the burn for restricted blood flow.

- Closely observe hourly fluid intake and urinary output, as well as blood pressure and cardiac rhythm; changes should be reported to the burn surgeon promptly.

- For patient with inhalation injury, regularly monitor level of consciousness, pulmonary function, and ability to ventilate; if patient is intubated and placed on a ventilator, frequent suctioning and assessment of the airway are priorities.

Rehabilitation Phase

Rehabilitation should begin immediately after the burn has occurred. Wound healing, psychosocial support, and restoring maximum functional activity remain priorities. Maintaining fluid and electrolyte balance and improving nutrition status continue to be important.

- In early assessment, obtain information about patient’s educational level, occupation, leisure activities, cultural background, religion, and family interactions.

- Assess self concept, mental status, emotional response to the injury and hospitalization, level of intellectual functioning, previous hospitalizations, response to pain and pain relief measures, and sleep pattern.

- Perform ongoing assessments relative to rehabilitation goals, including range of motion of affected joints, functional abilities in ADLs, early signs of skin breakdown from splints or positioning devices, evidence of neuropathies (neurologic damage), activity tolerance, and quality or condition of healing skin.

- Document participation and self care abilities in ambulation, eating, wound cleaning, and applying pressure wraps.

- Maintain comprehensive and continuous assessment for early detection of complications, with specific assessments as needed for specific treatments, such as postoperative assessment of patient undergoing primary excision.

Diagnosis

Nursing diagnoses for burn injuries include:

- Impaired gas exchange related to carbon monoxide poisoning, smoke inhalation, and upper airway obstruction.

- Ineffective airway clearance related to edema and effects of smoke inhalation.

- Fluid volume deficit related to increased capillary permeability and evaporative losses from burn wound.

- Hypothermia related to loss of skin microcirculation and open wounds.

- Pain related to tissue and nerve injury.

- Anxiety related to fear and the emotional impact of burn injury.

Planning & Goals

Main Article: 11 Burn Injury Nursing Care Plans

To implement the plan of care for a burn injury patient effectively, there should be goals that should be set:

- Maintenance of adequate tissue oxygenation.

- Maintenance of patent airway and adequate airway clearance.

- Restoration of optimal fluid and electrolyte balance and perfusion of vital organs.

- Maintenance of adequate body temperature.

- Control of pain.

- Minimization of patient’s and family’s anxiety.

Nursing Priorities

- Maintain patent airway/respiratory function.

- Restore hemodynamic stability/circulating volume.

- Alleviate pain.

- Prevent complications.

- Provide emotional support for patient/significant other (SO).

- Provide information about condition, prognosis, and treatment.

Nursing Interventions

Nursing care of a patient with burn injury needs to be precise and effective.

Promoting Gas Exchange and Airway Clearance

- Provide humidified oxygen, and monitor arterial blood gases (ABGs), pulse oximetry, and carboxyhemoglobin levels.

- Assess breath sounds and respiratory rate, rhythm, depth, and symmetry; monitor for hypoxia.

- Observe for signs of inhalation injury: blistering of lips or buccal mucosa; singed nostrils; burns of face, neck, or chest; increasing hoarseness; or soot in sputum or respiratory secretions.

- Report labored respirations, decreased depth of respirations, or signs of hypoxia to physician immediately; prepare to assist with intubation and escharotomies.

- Monitor mechanically ventilated patient closely.

- Institute aggressive pulmonary care measures: turning, coughing, deep breathing, periodic forceful inspiration using spirometry, and tracheal suctioning.

- Maintain proper positioning to promote removal of secretions and patent airway and to promote optimal chest expansion; use artificial airway as needed.

Restoring fluid and Electrolyte Balance

- Monitor vital signs and urinary output (hourly), central venous pressure (CVP), pulmonary artery pressure, and cardiac output.

- Note and report signs of hypovolemia or fluid overload.

- Maintain IV lines and regular fluids at appropriate rates, as prescribed. Document intake, output, and daily weight.

- Elevate the head of bed and burned extremities.

- Monitor serum electrolyte levels (eg, sodium, potassium, calcium, phosphorus, bicarbonate); recognize developing electrolyte imbalances.

- Notify physician immediately of decreased urine output; blood pressure; central venous, pulmonary artery, or pulmonary artery wedge pressures; or increased pulse rate.

Maintaining Normal Body Temperature

- Provide warm environment: use heat shield, space blanket, heat lights, or blankets.

- Assess core body temperature frequently.

- Work quickly when wounds must be exposed to minimize heat loss from the wound.

Minimizing Pain and Anxiety

- Use a pain scale to assess pain level (ie, 1 to 10); differentiate between restlessness due to pain and restlessness due to hypoxia.

- Administer IV opioid analgesics as prescribed, and assess response to medication; observe for respiratory depression in patient who is not mechanically ventilated.

- Provide emotional support, reassurance, and simple explanations about procedures.

- Assess patient and family understanding of burn injury, coping strategies, family dynamics, and anxiety levels. Provide individualized responses to support patient and family coping; explain all procedures in clear, simple terms.

- Provide pain relief, and give antianxiety medications if patient remains highly anxious and agitated after psychological interventions.

Monitoring and Managing Potential Complications

- Acute respiratory failure: Assess for increasing dyspnea, stridor, changes in respiratory patterns; monitor pulse oximetry and ABG values to detect problematic oxygen saturation and increasing CO2; monitor chest xrays; assess for cerebral hypoxia (eg, restlessness, confusion); report deteriorating

- respiratory status immediately to physician; and assist as needed with intubation or escharotomy.

- Distributive shock: Monitor for early signs of shock (decreased urine output, cardiac output, pulmonary artery pressure, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, blood pressure, or increasing pulse) or progressive edema. Administer fluid resuscitation as ordered in response to physical findings; continue monitoring fluid status.

- Acute renal failure: Monitor and report abnormal urine output and quality, blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine levels; assess for urine hemoglobin or myoglobin; administer increased fluids as prescribed.

- Compartment syndrome: Assess peripheral pulses hourly with Doppler; assess neurovascular status of extremities hourly (warmth, capillary refill, sensation, and movement); remove blood pressure cuff after each reading; elevate burned extremities; report any extremity pain, loss of peripheral pulses or sensation; prepare to assist with escharotomies.

- Paralytic ileus: Maintain nasogastric tube on low intermittent suction until bowel sounds resume; auscultate abdomen regularly for distention and bowel sounds.

- Curling’s ulcer: Assess gastric aspirate for blood and pH; assess stools for occult blood; administer antacids and histamine blockers (eg, ranitidine [Zantac]) as prescribed.

Restoring Normal fluid Balance

- Monitor IV and oral fluid intake; use IV infusion pumps.

- Measure intake and output and daily weight.

- Report changes (e.g., blood pressure, pulse rate) to physician.

Preventing Infection

- Provide a clean and safe environment; protect patient from sources of cross contamination (e.g., visitors, other patients, staff, equipment).

- Closely scrutinize wound to detect early signs of infection.

Monitor culture results and white blood cell counts.

- Practice clean technique for wound care procedures and aseptic technique for any invasive procedures. Use meticulous hand hygiene before and after contact with patient.

- Caution patient to avoid touching wounds or dressings; wash unburned areas and change linens regularly.

Maintaining Adequate Nutrition

- Initiate oral fluids slowly when bowel sounds resume; record tolerance—if vomiting and distention do not occur, fluids

- may be increased gradually and the patient may be advanced to a normal diet or to tube feedings.

- Collaborate with dietitian to plan a protein and calorie-rich diet acceptable to patient. Encourage family to bring nutritious and patient’s favorite foods. Provide nutritional and vitamin and mineral supplements if prescribed.

- Document caloric intake. Insert feeding tube if caloric goals cannot be met by oral feeding (for continuous or bolus feedings); note residual volumes.

- Weigh patient daily and graph weights.

Promoting Skin Integrity

- Assess wound status.

- Support patient during distressing and painful wound care.

- Coordinate complex aspects of wound care and dressing changes.

- Assess burn for size, color, odor, eschar, exudate, epithelial buds (small pearl-like clusters of cells on the wound surface), bleeding, granulation tissue, the status of graft take, healing of the donor site, and the condition of the surrounding skin; report any significant changes to the physician.

- Inform all members of the health care team of latest wound care procedures in use for the patient.

- Assist, instruct, support, and encourage patient and family to take part in dressing changes and wound care.

- Early on, assess strengths of patient and family in preparing for discharge and home care.

Relieving Pain and Discomfort

- Frequently assess pain and discomfort; administer analgesic agents and anxiolytic medications, as prescribed, before the pain becomes severe. Assess and document the patient’s response to medication and any other interventions.

- Teach patient relaxation techniques. Give some control over wound care and analgesia. Provide frequent reassurance.

- Use guided imagery and distraction to alter patient’s perceptions and responses to pain; hypnosis, music therapy, and virtual reality are also useful.

- Assess the patient’s sleep patterns daily; administer sedatives, if prescribed.

- Work quickly to complete treatments and dressing changes.

Encourage the patient to use analgesic medications before painful procedures.

- Promote comfort during healing phase with the following:

- oral antipruritic agents, a cool environment, frequent lubrication of the skin with water or a silica-based lotion, exercise and splinting to prevent skin contracture, and diversional activities.

Promoting Physical Mobility

- Prevent complications of immobility (atelectasis, pneumonia, edema, pressure ulcers, and contractures) by deep breathing, turning, and proper repositioning.

- Modify interventions to meet patient’s needs. Encourage early sitting and ambulation. When legs are involved, apply elastic pressure bandages before assisting patient to upright position.

- Make aggressive efforts to prevent contractures and hypertrophic scarring of the wound area after wound closure for a year or more.

- Initiate passive and active range-of-motion exercises from admission until after grafting, within prescribed limitations.

- Apply splints or functional devices to extremities for contracture control; monitor for signs of vascular insufficiency, nerve compression, and skin breakdown.

Strengthening Coping Strategies

- Assist patient to develop effective coping strategies: Set specific expectations for behavior, promote truthful communication to build trust, help patient practice coping strategies, and give positive reinforcement when appropriate.

- Demonstrate acceptance of patient. Enlist a non involved person for patient to vent feelings without fear of retaliation.

- Include patient in decisions regarding care. Encourage patient to assert individuality and preferences. Set realistic expectations for self care.

Supporting Patient and Family Processes

- Support and address the verbal and nonverbal concerns of the patient and family.

- Instruct family in ways to support patient.

- Make psychological or social work referrals as needed.

- Provide information about burn care and expected course of treatment.

- Initiate patient and family education during burn management. Assess and consider preferred learning styles; assess ability to grasp and cope with the information; determine barriers to learning when planning and executing teaching.

- Remain sensitive to the possibility of changing family dynamics.

Monitoring and Managing Potential Complications

- Heart failure: Assess for fluid overload, decreased cardiac output, oliguria, jugular vein distention, edema, or onset of S3 or S4 heart sounds.

- Pulmonary edema: Assess for increasing CVP, pulmonary artery and wedge pressures, and crackles; report promptly. Position comfortably with head elevated unless contraindicated. Administer medications and oxygen as prescribed and assess response.

- Sepsis: Assess for increased temperature, increased pulse, widened pulse pressure, and flushed, dry skin in unburned areas (early signs), and note trends in the data. Perform wound and blood cultures as prescribed. Give scheduled antibiotics on time.

- Acute respiratory failure and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS): Monitor respiratory status for dyspnea, change in respiratory pattern, and onset of adventitious sounds. Assess for decrease in tidal volume and lung compliance in patients on mechanical ventilation. The hallmark of onset of ARDS is hypoxemia on 100% oxygen, decreased lung compliance, and significant shunting; notify physician of deteriorating respiratory status.

- Visceral damage (from electrical burns): Monitor electrocardiogram (ECG) and report dysrhythmias; pay attention to pain related to deep muscle ischemia and report. Early detection may minimize severity of this complication. Fasciotomies may be necessary to relieve swelling and ischemia in the muscles and fascia; monitor patient for excessive blood loss and hypovolemia after fasciotomy.

- Contractures: Provide early and aggressive physical and occupational therapy; support patient if surgery is needed to achieve full range of motion.

- Impaired psychological adaptation to the burn injury:

- Obtain psychological or psychiatric referral as soon as evidence of major coping problems appears.

Promoting Activity Tolerance

- Schedule care to allow periods of uninterrupted sleep. Administer hypnotic agents, as prescribed, to promote sleep.

- Communicate plan of care to family and other caregivers.

- Reduce metabolic stress by relieving pain, preventing chilling or fever, and promoting integrity of all body systems to help conserve energy. Monitor fatigue, pain, and fever to determine amount of activity to be encouraged daily.

- Incorporate physical therapy exercises to prevent muscular atrophy and maintain mobility required for daily activities.

- Support positive outlook, and increase tolerance for activity by scheduling diversion activities in periods of increasing duration.

Improving Body Image and Self-Concept

- Take time to listen to patient’s concerns and provide realistic support; refer patient to a support group to develop coping strategies to deal with losses.

- Assess patient’s psychosocial reactions; provide support and develop a plan to help the patient handle feelings.

- Promote a healthy body image and selfconcept by helping patient practice responses to people who stare or ask about the injury.

- Support patient through small gestures such as providing a birthday cake, combing patient’s hair before visitors, and sharing information on cosmetic resources to enhance appearance.

- Teach patient ways to direct attention away from a disfigured body to the self within.

- Coordinate communications of consultants, such as psychologists, social workers, vocational counselors, and teachers, during rehabilitation.

Teaching Self-care

- Throughout the phases of burn care, make efforts to prepare patient and family for the care they will perform at home. Instruct them about measures and procedures.

- Provide verbal and written instructions about wound care, prevention of complications, pain management, and nutrition.

- Inform and review with patient specific exercises and use of elastic pressure garments and splints; provide written instructions.

- Teach patient and family to recognize abnormal signs and report them to the physician.

- Assist the patient and family in planning for the patient’s continued care by identifying and acquiring supplies and equipment that are needed at home.

- Encourage and support followup wound care.

- Refer patient with inadequate support system to home care resources for assistance with wound care and exercises.

- Evaluate patient status periodically for modification of home care instructions and/or planning for reconstructive surgery.

Evaluation

In a patient with burn injury, the expected outcomes are:

- Absence of dyspnea.

- Respiratory rate between 12 and 20 breaths/min.

- Lungs clear on auscultation,

- Arterial oxygen saturation greater than 96% by pulse oximetry.

- ABG levels within normal limits.

- Patent airway

- Respiratory secretions are minimal, colorless, and thin.

- Urine output between 0.5 and 1.0 mL/kg/h.

- Blood pressure higher than 90/60 mmHg.

- Heart rate less than 120 bpm.

- Body temperature remains between 36.1ºC and 38.3ºC

Gerontologic Considerations

The following are interventions you must consider when caring elderly people with burn injury.

- Elderly people are at higher risk for burn injury because of reduced coordination, strength, and sensation and changes in vision.

- Predisposing factors and the health history in the older adult influence the complexity of care for the patient.

- Pulmonary function is limited in the older adult and therefore airway exchange, lung elasticity, and ventilation can be affected.

- This can be further affected by a history of smoking.

- Decreased cardiac function and coronary artery disease increase the risk of complications in elderly patients with burn injuries. Malnutrition and presence of diabetes mellitus or other endocrine disorders present nutritional challenges and require close monitoring.

- Varying degrees of orientation may present themselves on admission or through the course of care making assessment of pain and anxiety a challenge for the burn team.

- The skin of the elderly is thinner and less elastic, which affects the depth of injury and its ability to heal.

Discharge and Home Care Guidelines

The focus of rehabilitative interventions is directed towards outpatient care, home care, or care in a rehabilitation center.

- Wound care. The patient and the family are instructed to wash small clean, open wounds daily with mild soap and water and to apply the prescribed topical agent or dressing.

- Education. The patient and the family require careful written and verbal instructions about pain management, nutrition, prevention of complications, specific exercises, and the use of pressure garments and splints.

- Follow up care. Patients who receive care in a burn center usually return to the burn clinic periodically for evaluation, modification of burn care instructions, and planning for reconstructive surgery.

- Referral. Patients who return home after a severe burn injury, those who cannot manage their own burn care, and those with inadequate support systems need referral for home care.

Documentation Guidelines

The nurse should document the following data to ensure that each care documented is a care that is done.

- Breath sounds and character of secretions.

- Respiratory rate, pulse oximetry/O2 saturation, vital signs.

- Plan of care and those involved in the planning.

- Teaching plan.

- Client’s response to interventions, teachings, and actions performed.

- Use of respiratory devices or adjuncts.

- Conditions that may interfere with oxygen supply.

- I&O, fluid balance, changes in weight, urine specific gravity.

- Attainment or progress toward desired outcomes.

- Modifications to the plan of care.

Practice Quiz: Burn Injury

Let’s reinforce what you’ve learned with this 5-item NCLEX practice quiz about burn injury. Please visit our nursing test bank for more NCLEX practice questions.

1. A full-thickness burn is:

A. Classified by the appearance of blisters.

B. Identified by the destruction of the dermis and epidermis.

C. Not associated with edema formation.

D. Usually very painful because of exposed nerve endings.

2. Fluids shifts during the first week of the acute phase of a burn injury that cause massive cell destruction result in:

A. Hypernatremia

B. Hypokalemia

C. Hyperkalemia

D. Hypercalcemia

3. As the first priority of care, a patient with burn injury will initially need:

A. A patent airway established.

B. An indwelling catheter inserted.

C. Fluids replaced.

D. Pain medication administered.

4. During the acute phase of burn injury, the nurse knows to assess for signs of potassium shifting:

A. Within 24 hours

B. Between 24 to 48 hours.

C. At the beginning of the third day.

D. Beginning on day 4 or day 5.

5. The leading cause of death in fire victims is believed to be:

A. Cardiac arrest

B. Carbon monoxide intoxication

C. Hypovolemic shock

D. Septicemia

Answers and Rationale

1. Answer: B. Identified by the destruction of the dermis and epidermis.

- B: A full thickness burn involves total destruction of the epidermis and dermis and, in some cases, the destruction of the underlying tissue, muscle, and bone.

- A: Blisters are identified in deep partial thickness burns.

- C: Edema is usually present in deep partial thickness burns.

- D: Exposed nerve endings are present in a deep partial thickness burn.

2. Answer: C. Hyperkalemia

- C: Immediately after burn injury hyperkalemia results from massive cell destruction.

- A: Hyponatremia and not hypernatremia is common during the first week of the acute phase, as water shifts from the interstitial space to the vascular space.

- B: Hypokalemia, instead hyperkalemia, occurs immediately after burn injury.

- D: There is no hypercalcemia in a burn injury.

3. Answer: A. A patent airway established.

- A: A patent airway is always the first priority in almost every injury because the body primarily needs oxygen to keep the body tissues running.

- B: An indwelling catheter would be inserted later on in the care of a patient with burn injury.

- C: Fluids would be replaced through IVF but it is not the priority immediately after the injury.

- D: Pain medication would be administered once all vital signs are stable.

4. Answer: A. Within 24 hours

- A: Immediately after burn injury, potassium shifting occurs and results in hyperkalemia.

- B: Assessing between 24 to 8 hours is also acceptable, yet this can be done immediately after the incident.

- C: Waiting for the third day to begin assessment is already too late and might cause complications.

- D: Having the assessment on the fourth day is too late and might cause complications.

5. Answer: B. Carbon monoxide intoxication

- B: Before the flames can reach a victim smoke from the fire would reach them and suffocate them first.

- A: Cardiac arrest is a disease that can occur later on in a burn patient.

- C: Hypovolemic shock is a consequence of the burn injury.

- D: Septicemia could occur late in the process of an inappropriately treated burn injury.

See Also

Posts related to Burn Injury:

Thank for all this information but we need to references , thanks

thanks a lot.. you help me do my work easier. great work. God bless.

Useful information. Helped me big time

Great one, thank you.

Many thanks 🙏 for this information

It helps me a lot

Thank you it is very informative 😇