The “strangling angel of children,” as diphtheria was once called, can be traced to the fourth-to-fifth century BC and was one of the most common causes of death among children in the prevaccine era. In this study guide, learn more about diphtheria, its pathophysiology, causes, signs and symptoms, nursing care management, and interventions.

What is Diphtheria?

- Diphtheria is an acute toxin-mediated disease caused by Corynebacterium diphtheriae.

- Unlike other diphtheroids (eg, coryneform bacteria), which are ubiquitous in nature, Corynebacterium diphtheriae is an exclusive inhabitant of human mucous membranes and skin.

- Diphtheria organisms usually remain in the superficial layers of skin lesions or respiratory mucosa, inducing local inflammatory reaction.

- Nontoxigenic strains also cause disease, which is mostly cutaneous and usually mild.

Pathophysiology

Diphtheriae toxin, which is secreted by toxigenic strains of Corynebacterium diphtheriae, is a single polypeptide of Mr 58,342.

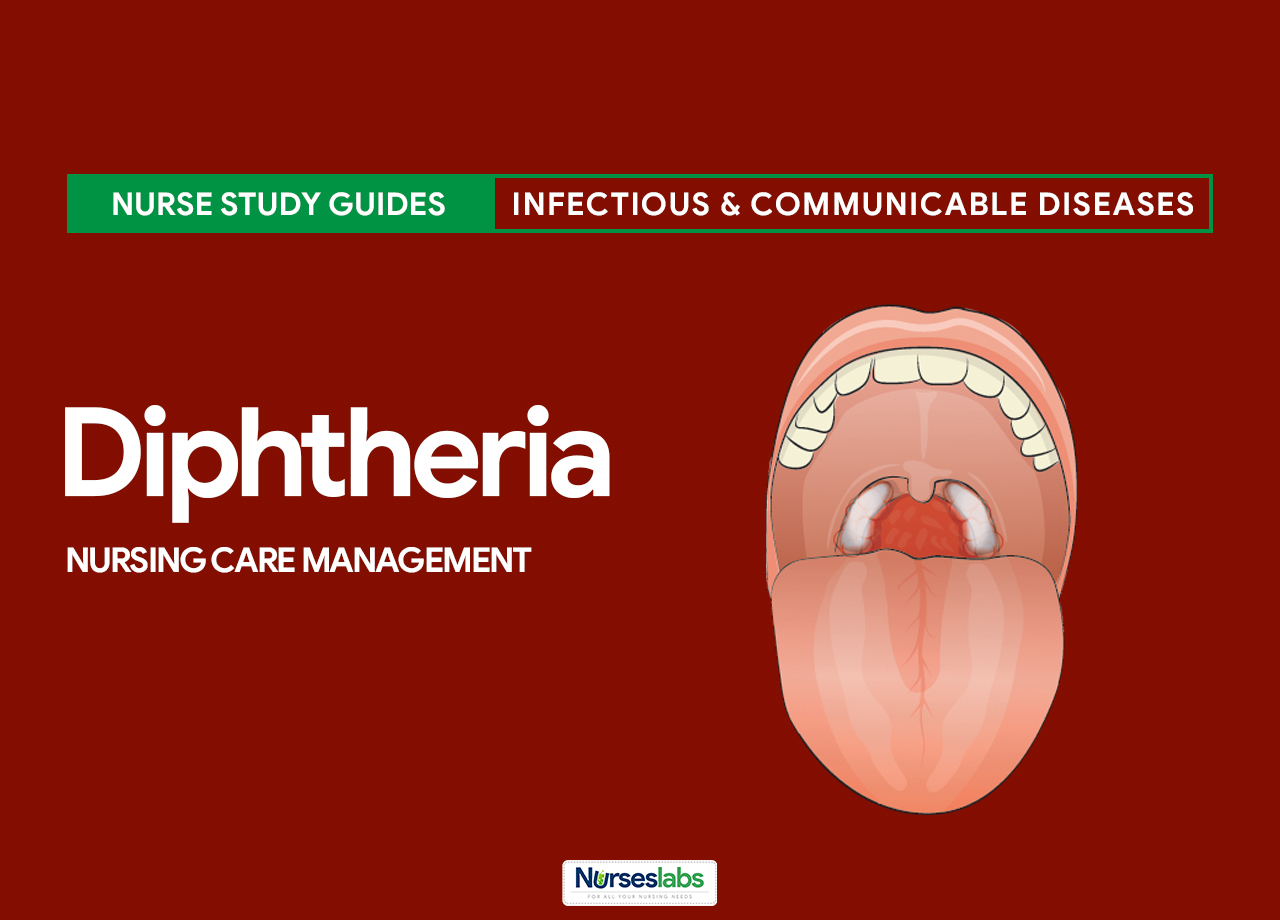

- Within the first few days of respiratory tract infection, a dense necrotic coagulum of organisms, epithelial cells, fibrin, leukocytes, and erythrocytes forms, advances, and becomes a gray-brown adherent pseudomembrane.

- Removal is difficult and reveals a bleeding edematous submucosa.

- Paralysis of the palate and hypopharynx is an early local effect of the toxin.

- Toxin absorption can lead to necrosis of kidney tubules, thrombocytopenia, cardiomyopathy, and demyelination of nerves.

- In the classic description of diphtheria, the primary focus of infection is the tonsils or pharynx in more then 90% of patients; the nose and larynx are the next most common sites.

Statistics and Incidences

Diphtheria is endemic in many parts of the world, including countries of the Caribbean and Latin America.

- Death due to mechanical airway obstruction or cardiac involvement with circulatory collapse occurs in at least 10% of patients with respiratory tract diphtheria.

- When diphtheria was endemic, it primarily affected children younger than 15 years; recently, the epidemiology has shifted to adults who lack natural exposure to toxigenic C diphtheriae in the vaccine era and those who have low rates of receiving booster injections.

- In the 27 sporadic cases of respiratory tract diphtheria reported in the United States in the 1980s, 70% occurred in persons older than 25 years.

Causes

Causes of diphtheria may include:

- Non Immunization. Among nonimmunized populations, diphtheria most often occurs during fall and winter, although summer outbreaks have occurred.

- Poor socioeconomic conditions. The disease spreads more quickly and is more prevalent in poor socioeconomic conditions, where crowding occurs and immunization rates are low.

- Travel history. International travel could pose a risk to persons who are unvaccinated or inadequately vaccinated.

Clinical Manifestations

Severity of disease due to C diphtheriae depends on the site of infection, the immunization status of the patient, and the dissemination of toxin.

- Tonsils and pharynx. Tonsillar and pharyngeal diphtheria are most common; symptoms begin with a sore throat, usually in the absence of systemic complaints; fever, if it occurs, is usually lower than 102°F, and malaise, dysphagia, and headache are not prominent features.

- Pseudomembrane. In individuals with diphtheria infection who are not immune, membrane formation begins after the 2-day to 5-day incubation period and grows to involve the pharyngeal walls, tonsils, uvula, and soft palate; the membrane may extend to the larynx and trachea, causing airway obstruction and eventual suffocation.

- Edema. Marked edema of the neck may lead to a bull-neck appearance with a distinct collar of swelling; the patient throws the head back to relieve pressure on the throat and larynx; erasure edema associated with pharyngeal diphtheria obliterates the angle of the jaw, the borders of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, and the medial border of the clavicles.

- Larynx. In a minority of patients, the larynx is the initial site of infection, with initial presenting symptoms similar to laryngotracheobronchitis from other causes; initial hoarseness may progress to loss of voice and severe respiratory tract obstruction; initially, nasal diphtheria may present as a common viral upper respiratory tract infection; a foul odor may develop.

- Skin. Cutaneous diphtheria may occur at one or more sites, usually localized to areas of previous mild trauma or bruising.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

Diagnostic tests used to confirm infection combine isolation of C diphtheriae on cultures with toxigenicity testing.

- Bacteriologic culturing. Bacteriologic culturing is essential to confirm the diagnosis of diphtheria.

- Toxigenicity testing. Perform toxigenicity testing using the Elek test to determine if the C diphtheriae isolate produces toxin.

- Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test. The PCR test can detect nonviable C diphtheriae organisms from specimens taken after antibiotic therapy has been initiated.

Medical Management

Critical care needs and complications must be addressed.

- Specific antitoxin. Specific antitoxin is the mainstay of therapy and should be administered on the basis of clinical diagnosis because it neutralizes free toxin only.

- Isolation. Individuals are placed in strict isolation (respiratory tract colonization) or contact isolation (cutaneous colonization only) until at least 2 subsequent cultures taken 24 hours apart after cessation of therapy demonstrate negative results.

Pharmacologic Management

Appropriate antibiotic therapy should be administered simultaneously with the antitoxin.

- Antibiotic agents. Antimicrobial therapy is indicated to halt toxin production, treat localized infection, and prevent transmission of the organism to patient contacts.

- Antipyretic agents. These agents inhibit central synthesis and release of prostaglandins that mediate the effect of endogenous pyrogens in the hypothalamus; thus, they promote the return of the set-point temperature to normal.

- Vaccines. Diphtheria toxoid is typically combined with tetanus and acellular pertussis for children younger than 7 years; active immunization increases resistance to infection.

Nursing Management

Nursing management of a client with diphtheria include the following:

Nursing Assessment

Assessment of a client with diphtheria include:

- History. Onset of symptoms of respiratory diphtheria typically follows an incubation period of 2-5 days (range, 1-10d); symptoms initially are general and nonspecific, often resembling a typical viral upper respiratory infection (URI).

- Physical examination. The patient has a low-grade fever but is toxic in appearance, and also may have a swollen neck; cardiac toxicity typically occurs after 1-2 weeks of illness following improvement in the pharyngeal phase of the disease, and neurologic toxicity is proportional to the severity of the pharyngeal infection.

Nursing Diagnosis

Based on the assessment data, the major nursing diagnosis are:

- Hyperthermia related to the release of an exotoxin.

- Imbalanced nutrition: less than body requirements related to painful swallowing.

- Ineffective airway clearance related to pseudomembrane blocking the airway.

Nursing Care Planning and Goals

The nursing care planning goals for Diptheria includes:

- The client will be able to maintain a normal body temperature.

- The client will be able to demonstrate and maintain a normal body weight.

- The client will be able to maintain a clear airway.

Nursing Interventions

The nursing interventions for Diptheria are the following:

- Improve thermoregulation. Maintain room temperature; advise the client to wear thin clothes that absorb sweat easily; encourage to increase oral fluid intake, and administer antipyretics as ordered.

- Improve caloric intake. Monitor calorie intake and quality of food consumption; provide foods that stimulate the appetite, and measure the bodyweight daily.

- Improve airway clearance. Auscultate breath sounds, note the presence of an additional breath sounds; place the client in a comfortable position that can aid maximum lung expansion; help performs chest physiotherapy; and suction secretions as needed.

Evaluation

Nursing goals are met as evidenced by:

- The client was able to maintain a normal body temperature.

- The client was able to demonstrate and maintain a normal body weight.

- The client was able to maintain a clear airway.

Documentation Guidelines

Documentation in a client with diphtheria include:

- Individual findings, include factors affecting, interactions, nature of social exchanges, specifics of individual behavior.

- Cultural and religious beliefs, and expectations.

- Plan of care.

- Teaching plan.

- Responses to interventions, teaching, and actions performed.

- Attainment or progress toward the desired outcome.

References

Sources and references for this Diptheria study guide:

- Black, J. M., & Hawks, J. H. (2005). Medical-surgical nursing. Elsevier Saunders,. [Link]

- Kimberlin, D. W. (2018). Red Book: 2018-2021 report of the committee on infectious diseases (No. Ed. 31). American academy of pediatrics.

- Oshinsky, D. M. (2005). Polio: an American story. Oxford University Press. [Link]

- Willis, L. (2019). Professional guide to diseases. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Link]

Leave a Comment