Have a deeper understanding of the functions of our skin and its allies with the integumentary system guide; for nursing students eager to grasp the anatomy and physiology of our first line of defense. This guide offers an updated, in-depth review of skin structure, function, and lifespan changes, along with nursing implications, presented in a clear, stepwise manner.

What is the Integumentary System?

The integumentary system, consisting of skin, hair, nails, and associated glands, serves as the body’s primary defense mechanism. The skin is not only the largest organ (covering ~2 m² of surface area and accounting for around 15% of an adult’s body weight) but also one of the most dynamic, serving as a protection from infection, injury, and dehydration.

In nursing, understanding the anatomy and physiology of the integumentary system is essential for patient assessment and care. Assessment of the skin often reflect an individual’s health status, and proper skin care is vital in preventing wounds, pressure ulcers, and infections.

For practice applying this knowledge, see our Integumentary Disorders NCLEX Practice Quiz.

Functions of the Integumentary System

The integumentary system performs several essential functions such as protection, temperature regulation, excretion, vitamin D synthesis, and sensation:

Protection

The primary role of the integumentary system is protection, which it provides through multiple mechanisms:

- Mechanical barrier. The skin acts as a durable physical shield that absorbs friction and pressure, reducing injury from everyday bumps and abrasions. The layered structure of the epidermis and dermis gives the skin strength and resistance to tearing.

- Chemical barrier. Keratin strengthens the skin and limits penetration by irritants, while sebum creates a slightly acidic surface that inhibits bacterial growth.

- Barrier to harmful substances.Tightly packed, keratinized cells and surface lipids prevent toxic chemicals, pollutants, and other harmful agents from entering the body.

- UV protection. Melanin absorbs and disperses ultraviolet (UV) radiation, lowering the risk of DNA damage, sunburn, premature aging, and skin cancer.

- Defense against microorganisms. Intact skin serves as the first line of defense against bacteria, fungi, and viruses and contains immune cells that help detect and respond to pathogens.

- Prevention of fluid loss. Keratin and intercellular lipids form a waterproof barrier that minimizes water and electrolyte loss, helping maintain hydration.

Temperature Regulation

The integumentary system helps regulate body temperature by:

- Sweat production. Sweat glands release moisture that cools the body through evaporation, especially during exercise, fever, or heat exposure.

- Blood flow regulation. Dermal blood vessels dilate to release heat and constrict to conserve heat, adjusting body temperature as needed.

Nursing Note: Cool, clammy skin may indicate shock or impaired perfusion and requires prompt assessment.

Excretion

The skin contributes to waste elimination by:

- Excreting small amounts of waste. Sweat contains urea, uric acid, ammonia, and excess electrolytes, supporting minor detoxification.

- Maintaining fluid and electrolyte balance. Regulation of sweat production helps control fluid levels and electrolyte concentrations.

Nursing Note: Patients with renal failure may develop uremic frost—white crystalline deposits on the skin caused by excess urea excreted through sweat.

Vitamin D Synthesis

The skin plays a vital role in vitamin D production by:

- Converting precursors through sunlight exposure. UVB rays convert 7-dehydrocholesterol in the skin into vitamin D₃ (cholecalciferol).

- Supporting calcium absorption. Vitamin D processed by the liver and kidneys promotes calcium and phosphate absorption, supporting bone health and immune function.

Nursing Note: Older adults and bed-bound patients may need monitoring or supplementation to prevent vitamin D deficiency.

Sensation

The integumentary system enables sensory perception by:

- Detecting stimuli. Specialized receptors sense pain, temperature, touch, and pressure.

- Triggering protective responses. Sensory input allows quick reactions, such as withdrawing from heat or sharp objects, helping prevent injury.

Nursing Note: Regular sensory assessments are important for patients with diabetes to detect peripheral neuropathy and prevent unnoticed injuries.

Anatomy of the Integumentary System

The skin consists of two primary layers: an outer epidermis and an inner dermis . These layers are firmly interconnected and together form the cutaneous membrane. Beneath the dermis lies the subcutaneous tissue (hypodermis), a layer of adipose (fat) and areolar connective tissue that is not technically part of the skin but attaches it to underlying tissues. The subcutaneous layer provides insulation, energy storage, and cushioning and is rich in blood vessels and nerves that extend into the dermis. For descriptive purposes, we also include the skin appendages (sweat glands, oil glands, hair, and nails) as part of the integumentary system.

Epidermis

The epidermis is the thin, outermost layer of the skin composed of stratified squamous epithelial tissue. It is avascular (lacks blood vessels); instead, its cells are nourished through diffusion from the underlying dermis. The epidermis undergoes keratinization, a process where cells produce keratin, a tough, fibrous protein that enhances the skin’s resistance to physical stress and water loss.

Most cells in the epidermis are keratinocytes, which synthesize keratin and form a protective, cornified outer layer.

Layers of the Epidermis (Strata)

The epidermis is organized into five layers, listed from deepest to most superficial.

- Stratum Basale (Basal Layer). This is the deepest layer of the epidermis and rests directly on the basement membrane. It contains mitotically active basal cells (stem cells) that divide to form new keratinocytes and also houses melanocytes and Merkel cells.

- Stratum Spinosum (Spiny Layer). Keratinocytes in this layer begin to synthesize keratin and are connected by desmosomes, which give them a spiny appearance under a microscope. This layer provides strength and flexibility to the skin.

- Stratum Granulosum (Granular Layer). Cells in this layer flatten and accumulate dark-staining granules of keratohyalin and lamellar bodies, which contribute to the skin’s waterproofing. It marks the transition between metabolically active cells and the dead cells of the upper layers.

- Stratum Lucidum (Clear Layer- only in thick skin). Found only in the thick skin of the palms and soles, this thin, translucent layer consists of dead, flattened keratinocytes. It adds an extra barrier of protection in high-friction areas.

- Stratum Corneum (Horny Layer). This outermost layer is composed of 20–30 layers of dead, fully keratinized cells that are continuously shed and replaced. It serves as the skin’s primary barrier against environmental hazards, dehydration, and pathogens.

Epidermal Cell Types

The following are the different cell types of the epidermis:

- Keratinocytes. Keratinocytes are the most abundant cells in the epidermis and are responsible for producing keratin, a tough protein that strengthens the skin and reduces water loss. As they mature, they migrate upward through the epidermal layers, eventually forming the outermost protective layer, the stratum corneum.

- Melanocytes. Melanocytes are located in the stratum basale and produce melanin, the pigment that gives skin its color. Melanin is transferred to surrounding keratinocytes, where it accumulates to protect the nucleus from UV radiation.

- Langerhans Cells. Langerhans cells are dendritic immune cells found primarily in the stratum spinosum. They detect and present foreign antigens to immune cells, playing a key role in the skin’s defense against pathogens.

- Merkel Cells. Merkel cells are sensory receptors located in the stratum basale, often near nerve endings. They are involved in detecting light touch and pressure, particularly in areas such as the fingertips and lips.

Dermis

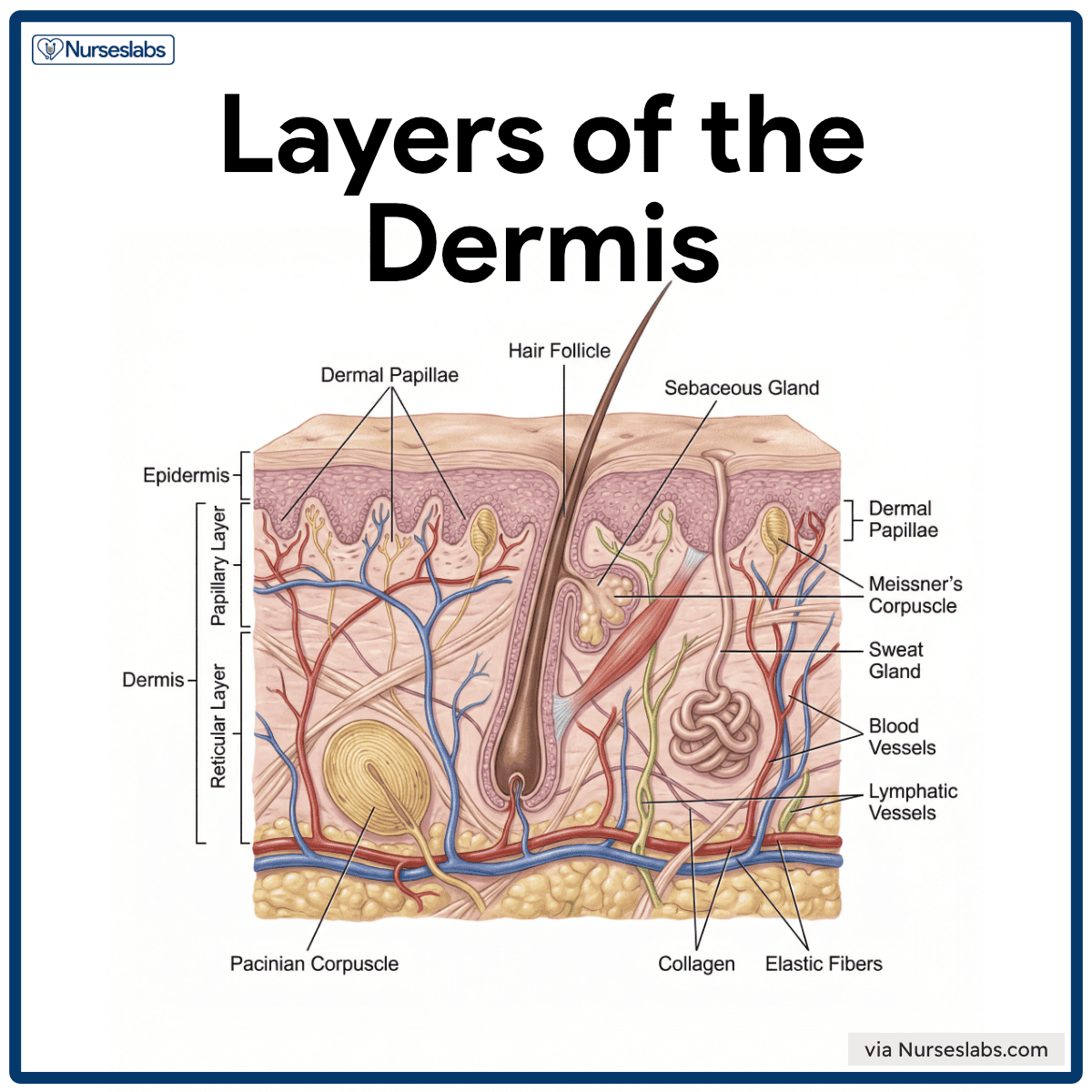

The dermis lies beneath the epidermis and is composed of vascularized connective tissue that provides the skin with strength, elasticity, and flexibility. It contains blood vessels, nerves, glands, and hair follicles that support and nourish the epidermis. The dense (fibrous) connective tissue making up the dermis consists of two major regions, the papillary and reticular regions.

- Papillary Layer. The papillary layer is the upper portion of the dermis made of loose areolar connective tissue and contains capillaries, nerve endings, and Meissner’s corpuscles for touch sensation. Its dermal papillae interlock with the epidermis and form friction ridges, which create fingerprints and enhance grip.

- Reticular Layer. The reticular layer is the deeper, thicker part of the dermis, composed of dense irregular connective tissue rich in collagen and elastic fibers, providing strength and elasticity to the skin. It houses various structures, including hair follicles, sebaceous and sweat glands, blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and deep pressure receptors called Pacinian corpuscles that reside in the deeper dermis (and subcutaneous tissue) to sense firm pressure and vibrations.

Other Key Structural Components of Dermis

- Collagen. Collagen is the main structural protein in the dermis. It helps resist tearing and maintains skin integrity. It also binds water, contributing to skin hydration.

- Elastic fibers. Elastic fibers provide flexibility and recoil. With age and UV exposure, these fibers degrade, contributing to the development of sagging and wrinkles.

- Blood vessels. Dermal capillaries nourish the avascular epidermis and adjust blood flow to help regulate body temperature (via vasodilation and vasoconstriction).

- Lymphatic Vessels. These vessels help maintain tissue fluid balance and transport immune cells to protect against infection.

- Hair Follicles. Hair follicles extend from the epidermis into the dermis and contribute to thermoregulation, sensation, and minor protection.

- Nerve Endings and Sensory Receptors. Various sensory receptors (e.g., Meissner’s corpuscles, Pacinian corpuscles, free nerve endings) transmit signals to the nervous system for sensory perception and protective reflexes.

- Meissner’s Corpuscles. Meissner’s corpuscles are specialized touch receptors located in the papillary layer of the dermis, particularly in sensitive areas like the fingertips, lips, and palms. These receptors respond to light touch and fine texture.

- Pacinian Corpuscles. Pacinian corpuscles are deep pressure receptors situated in the lower dermis and subcutaneous tissue. These structures detect intense pressure and vibrations from mechanical stimuli.

Skin Appendages (Hair, Nails, and Glands)

The integumentary system comprises several appendages derived from the epidermis, but they are primarily located in the dermis. These appendages, including cutaneous glands, hair, hair follicles, and nails, play important roles in protection, thermoregulation, sensation, and skin maintenance.

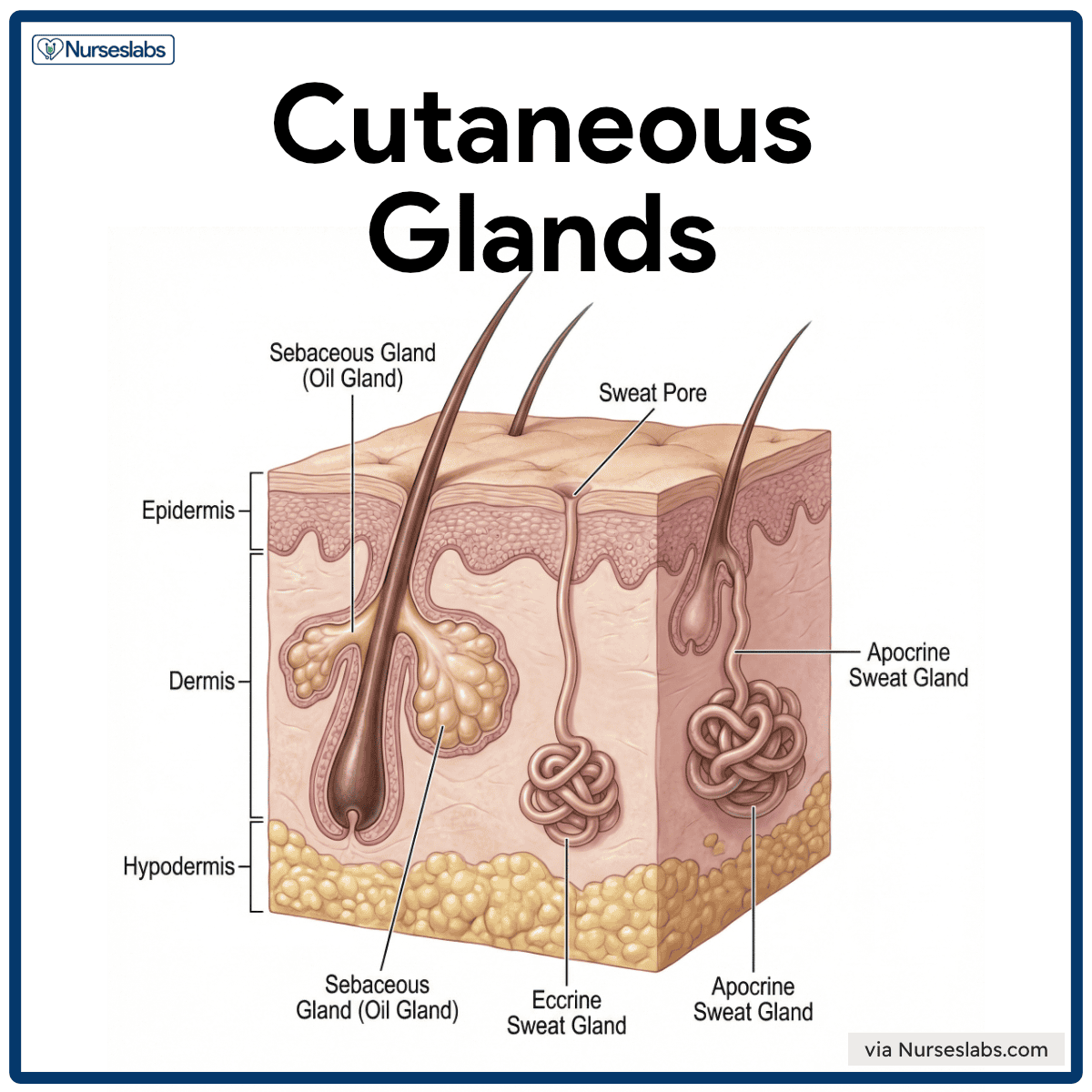

Cutaneous Glands (Sebaceous and Sweat Glands)

The skin contains two main types of exocrine glands: sebaceous glands and sweat glands. Both are derived from epidermal tissue and extend into the dermis.

- Sebaceous glands (oil glands). Holocrine glands that secrete sebum, an oily substance composed of fats, cholesterol, proteins, and cell fragments. It is found throughout the skin except on the palms and soles.

- Sweat glands (sudoriferous glands). These are tubular glands that produce sweat, and they are located throughout the body in varying densities. Humans have millions of sweat glands, and they come in two varieties: eccrine and apocrine.

- Eccrine sweat glands. Most numerous and widely distributed (especially on the forehead, palms, and soles). Simple coiled tubular glands that secrete sweat directly onto the skin surface. Sweat is 99% water with some salts, urea, uric acid, lactic acid, and vitamin C. Function are mostly for evaporative cooling for thermoregulation.

- Apocrine sweat glands . These are located mainly in the axillae, nipple area, and anogenital region. Ducts open into hair follicles, not the skin surface. Secretion contains lipids and proteins, making it thicker than eccrine sweat. Initially odorless, it develops odor when broken down by skin bacteria. Activated during puberty and stimulated by stress or sexual arousal. Do not play a significant role in temperature regulation.

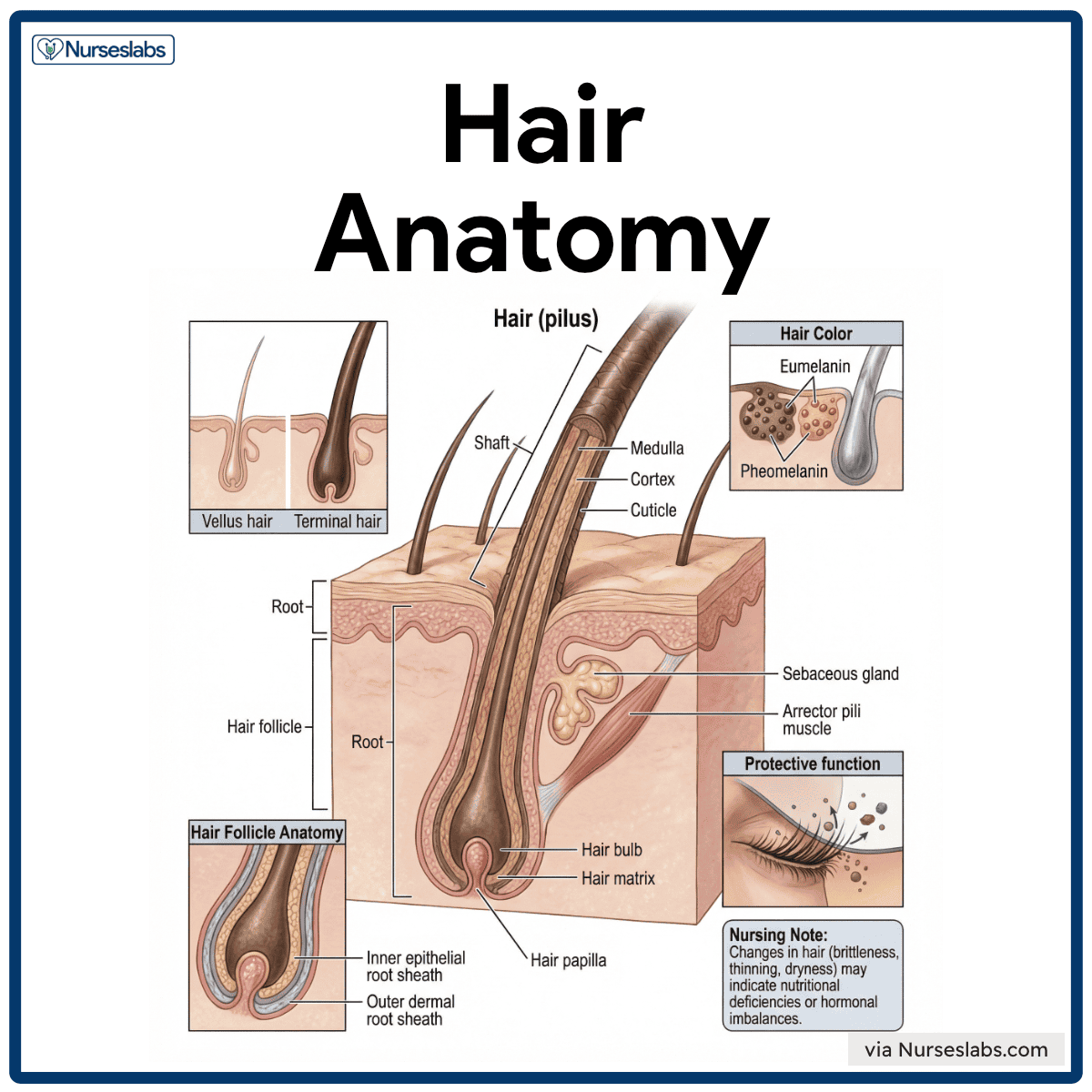

Hair and Hair Follicles

Hair (pilus) is composed of dead, keratinized epithelial cells that originate in the hair follicles. It serves minor protective and sensory roles, shielding the body and detecting external stimuli.

- Vellus hair. Fine, unpigmented hair that covers much of the body, providing minimal insulation and protection.

- Terminal hair. Coarser, pigmented hair found in areas such as the scalp, eyebrows, armpits, and pubic region, offering increased protection and sensory input.

- Protective function. Eyelashes and nasal hairs act as physical barriers, trapping dust and preventing foreign particles from entering sensitive regions.

Structure of Hair

- Shaft. The visible portion of the hair above the skin surface; the shape of the hair follicle determines its texture and appearance.

- Root. The part of the hair embedded within the skin, which anchors the hair into the follicle.

- Hair bulb. The base of the hair root, expanded in structure, is located in the dermis, where hair production occurs.

- Hair matrix. A layer of actively dividing cells in the bulb is responsible for hair growth.

- Hair papilla. A dermal component that contains capillaries and connective tissue, supplying nutrients and oxygen to the matrix.

Hair Composition

- Medulla. The central core, present in thick or coarse hair, is composed of large cells and air spaces.

- Cortex. The thickest layer that contains pigment (melanin), providing hair with its color and strength.

- Cuticle. The outermost layer of overlapping cells that protects the inner layers from damage and dehydration.

Hair Color

Hair color is determined by melanocytes in the hair bulb that deposit melanin into the cortex of the hair.

- Eumelanin. Produces black or brown hair shades.

- Pheomelanin. Produces red or blonde hair shades.

With aging, melanin production diminishes, leading to gray or white hair due to a reduction in pigment.

Hair Follicle Anatomy

Hair follicles are composed of two layers

- Inner epithelial root sheath. Surrounds and protects the growing hair shaft, supporting hair structure.

- Outer dermal root sheath. Provides nourishment and structural integrity to the follicle.

Hair follicles are associated with

- Sebaceous glands. Secrete sebum to lubricate and protect both hair and skin.

- Arrector pili muscles. Small bands of smooth muscle attached to hair follicles that contract in response to cold or emotional stimuli, causing the hair to stand up (goosebumps).

Nursing Note: Changes in hair (brittleness, thinning, dryness) may indicate nutritional deficiencies or hormonal imbalances.

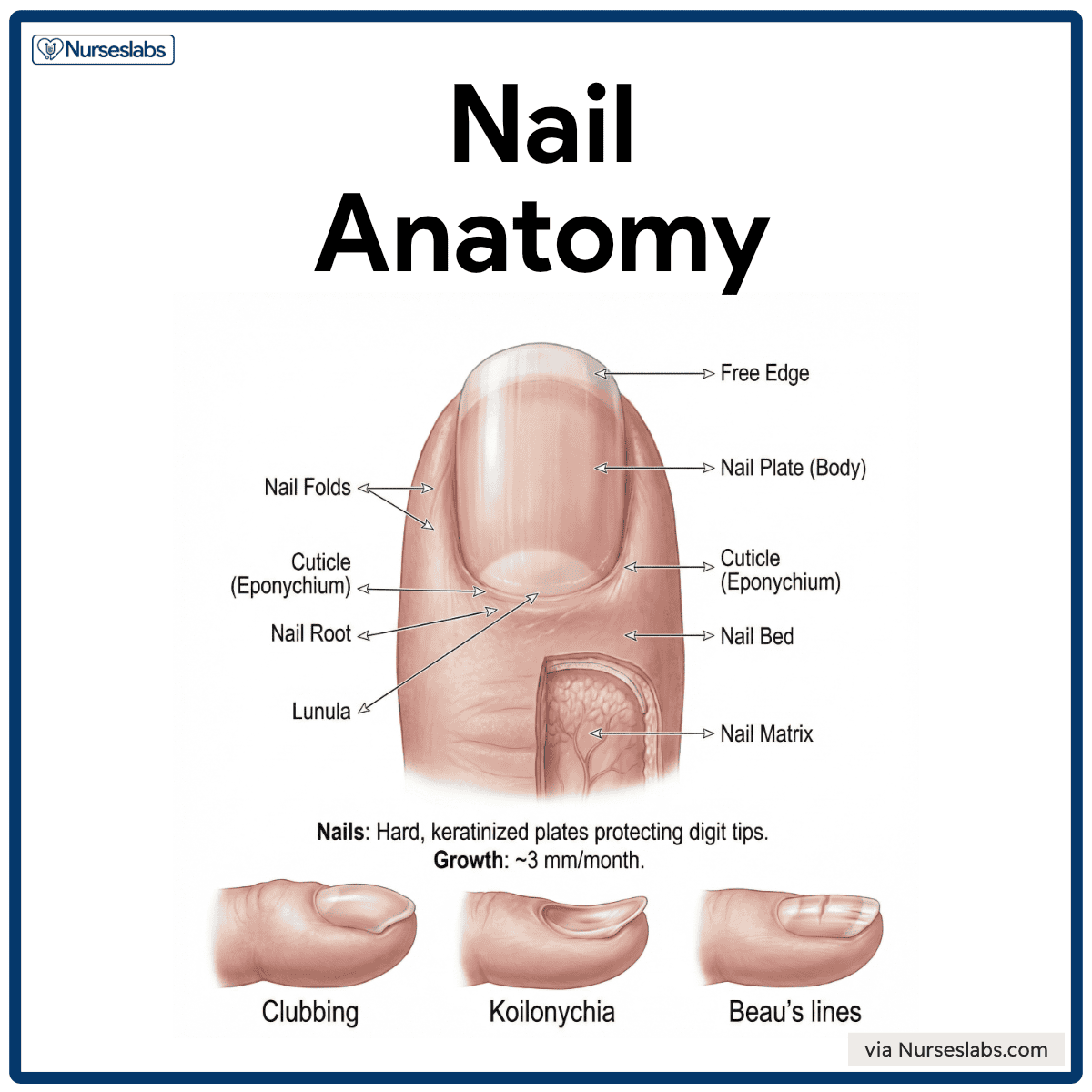

Nails

Nails are hard, keratinized plates located at the tips of fingers and toes. They protect the digit tips and assist in fine motor tasks, such as picking up small objects.

Nail Anatomy

- Nail Plate (Body). Visible portion of the nail.

- Free Edge. A distal whitish edge that extends past the fingertip

- Nail Root. The proximal portion is embedded under the skin fold.

- Nail Folds. Skin folds around the nail; includes the cuticle (eponychium).

Supporting Structures

- Nail Bed. Epidermal layer under the nail plate; appears pink due to vascular dermis.

- Nail Matrix. Growth zone deep to the nail root; produces new nail cells.

- Lunula. Crescent-shaped white area at the nail base where cells are not yet fully keratinized.

Growth and Clinical Relevance

- Fingernails grow ~3 mm/month.

- Nail growth can reflect systemic health; slowed growth or changes may indicate malnutrition, illness, or oxygenation issues.

Clinical Signs

- Clubbing. Characterized by a bulbous enlargement of the fingertips and curved nails; often associated with chronic hypoxia, such as in lung or heart disease.

- Koilonychia (spoon-shaped nails). Nails appear thin and concave, often associated with iron-deficiency anemia or chronic blood loss.

- Beau’s lines. Horizontal depressions across the nail plate that reflect temporary interruption of nail growth due to severe illness, stress, or malnutrition.

Nursing Note. Nail care is essential, particularly for patients with diabetes or vascular disease, to prevent infections and monitor systemic health.

Physiology of the Integumentary System

Beyond its structure, the integumentary system carries out several physiological processes essential to homeostasis. We have touched on many of these already (protection, temperature regulation, sensation, etc.). In this section, we’ll highlight how skin color is determined and how hair and nails grow – processes often encountered in both health and disease states.

Development of Skin Color

A combination of pigments and physiological conditions influences skin color. Three primary pigments contribute to baseline skin tone, namely melanin, carotene, and hemoglobin.

- Melanin is a brown to black or yellow-brown pigment produced by melanocytes in the epidermis. Increased melanin results in darker skin tones, including tanning after sun exposure.

- Carotene is a yellow-orange pigment acquired through diet (e.g., carrots, leafy vegetables). It accumulates in the stratum corneum and fat, giving the skin a yellow-orange tint with high dietary intake.

- Hemoglobin is an oxygen-binding pigment in red blood cells that imparts a pinkish tone, especially in fair-skinned individuals with translucent epidermis.

Skin color may also change temporarily due to emotional states or clinical conditions

- Erythema. Redness caused by increased blood flow during fever, inflammation, embarrassment, or allergy.

- Pallor. Paleness from vasoconstriction due to fear, anemia, hypotension, or shock.

- Jaundice. Yellowing from bilirubin buildup in liver dysfunction (e.g., hepatitis). Common in newborns with immature livers.

- Bruising (Ecchymosis). Blue or purple patches from trauma and blood leakage into tissues. Color changes during healing.

- Cyanosis. Bluish discoloration, especially in lips or nail beds, indicates low oxygenation (e.g., respiratory or cardiac failure).

- Bronzing. A metallic brown tone is often seen in endocrine disorders, such as Addison’s disease or hemochromatosis.

Nursing Note. Skin tone assessment helps identify systemic illnesses and underlying conditions, making it a fundamental nursing skill.

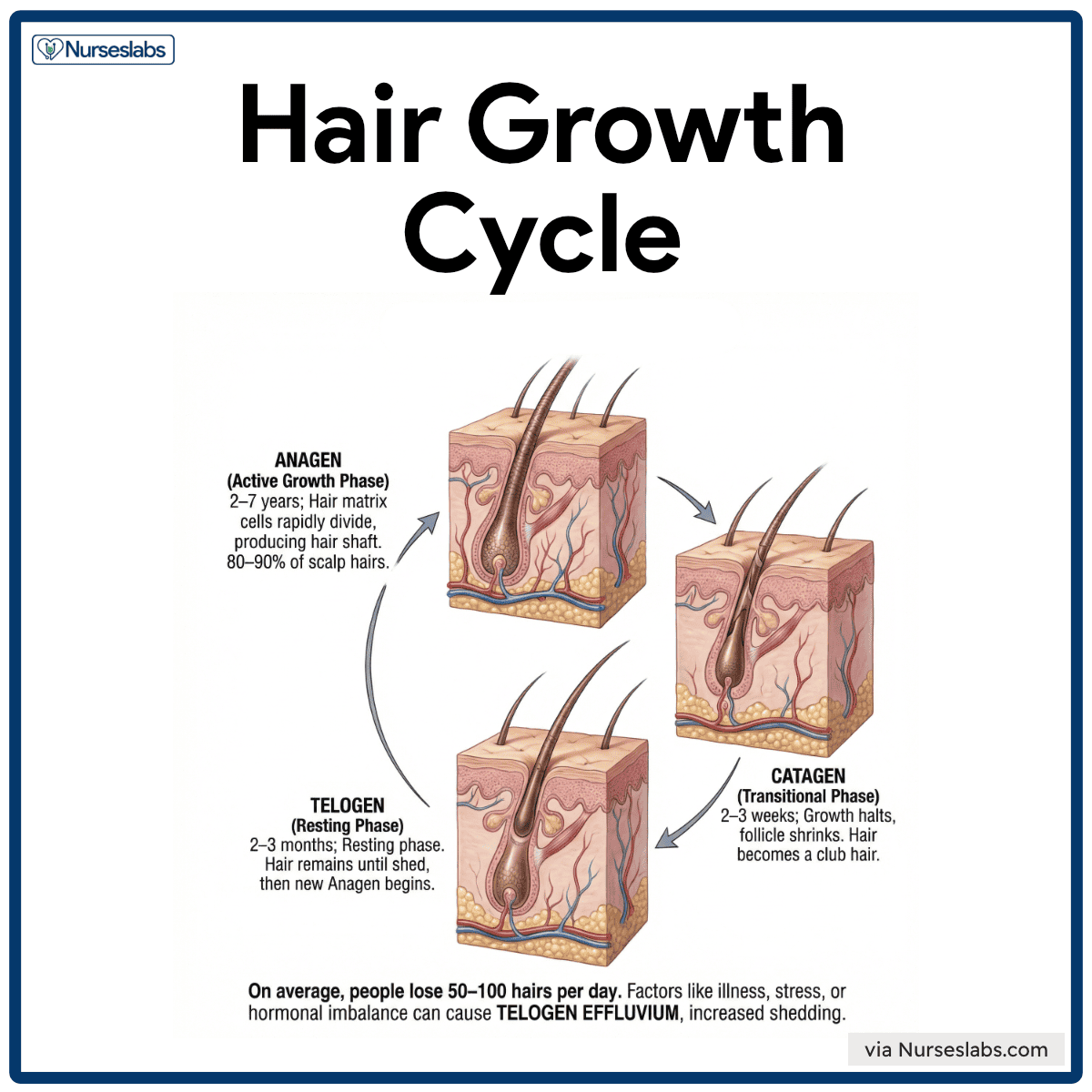

Hair Growth Cycle

Hair grows in a cyclical pattern through three phases

- Anagen. Active growth phase lasting 2–7 years; hair matrix cells rapidly divide, producing the hair shaft. Around 80–90% of scalp hairs are in this phase.

- Catagen. A short 2–3 week transitional phase where growth halts and the follicle shrinks. Hair detaches from its blood supply and becomes a club hair.

- Telogen. Resting phase lasting 2–3 months. Hair remains in place until shed, then a new anagen phase begins.

Nursing Note: Understanding the hair growth cycle helps nurses educate patients on hair loss conditions and what outcomes to expect (e.g., hair lost due to chemotherapy, which forces follicles into resting, often regrows when treatment stops and follicles resume anagen).

Nail Growth

Nails grow continuously from the nail matrix, a specialized region of the epidermis beneath the cuticle. Fingernails grow about 0.1 mm per day, with toenails growing more slowly. Nail growth is influenced by nutrition, oxygenation, trauma, and systemic disease.

- Germinal matrix. Located under the proximal nail fold, it is the primary growth zone where cells divide and become keratinized.

- Lunula. The visible white crescent near the cuticle appears pale due to the thickened underlying matrix.

- Sterile matrix. Lies beneath the nail plate and attaches the nail to the nail bed, contributing to nail strength.

- Dorsal root. Contributes to the top layers of the nail, providing a smooth and shiny surface.

Developmental Physiology of the Integumentary System

The integumentary system is a dynamic organ that undergoes profound physiological evolution from infancy through senescence. Structural variances—ranging from the permeable barrier of the neonate to the atrophic tissue of the elderly—dictate distinct clinical risks at every stage. Mastering these developmental changes is fundamental for accurate assessment, injury prevention, and the implementation of age-appropriate therapeutic management.

The Neonatal and Infant Period

The transition from an aquatic intrauterine environment to an arid extrauterine world presents an immediate challenge to the neonatal integument. Clinically, the most significant feature is the thinness of the epidermis and a functionally immature stratum corneum. This structural deficit results in high transepidermal water loss (TEWL), rendering infants highly susceptible to rapid dehydration and thermal instability compared to adults. Furthermore, the skin barrier exhibits increased permeability, which allows for the rapid absorption of topical agents; this necessitates extreme caution with medication dosages to avoid systemic toxicity.

While the newborn is often protected initially by vernix caseosa—a biofilm of lipids and proteins that facilitates acid mantle formation—this is transient. The infant also possesses inefficient vasoconstriction and limited subcutaneous fat, leading to immature thermoregulation. Consequently, nursing care must focus on maintaining the acid mantle (pH 4.5–5.5) and preventing heat loss.

Early and Middle Childhood

As development progresses into childhood, the dermo-epidermal junction strengthens and the skin layers thicken, significantly increasing tensile strength. However, clinicians must remember that the ratio of Body Surface Area (BSA) to weight remains higher in children than in adults, maintaining a risk for heat loss and drug absorption.

Physiologically, this period is characterized by low sebaceous activity; prior to adrenarche, these glands are quiescent, resulting in lower lipid content and generally dryer skin. A distinct advantage of pediatric skin is its high metabolic activity, which allows for accelerated re-epithelialization and rapid wound healing following injury. Therefore, the clinical focus shifts from barrier protection to traumatic injury management (abrasions, lacerations) and the prevention of secondary infections such as Staphylococcus aureus colonization.

Adolescence

The onset of puberty initiates a massive surge in androgens, specifically testosterone and DHT, which triggers rapid glandular and follicular differentiation. The most visible clinical manifestation is sebaceous hypertrophy, where androgens stimulate glands to enlarge and overproduce sebum, frequently leading to follicular obstruction and Acne vulgaris. Simultaneously, the apocrine glands in the axillary and inguinal regions become functional, altering the local microbiome and resulting in body odor (bromhidrosis).

Follicular units also respond to hormones via terminal hair differentiation, where fine vellus hair transitions to coarse terminal hair in androgen-sensitive zones. Nursing management during this phase is largely centered on the treatment of inflammatory dermatoses to prevent permanent scarring and education regarding hygiene protocols.

Adulthood

In early adulthood, the integument reaches its homeostatic peak, characterized by a dense collagen matrix and elastin fibers that provide optimal turgor. Stable glandular function is achieved, with balanced sebaceous and sudoriferous output. However (and unfortunately), even in the absence of disease, the process of aging begins immediately. While intrinsic aging is chronologically inevitable, the clinical picture is often dominated by extrinsic aging, or photoaging.

Cumulative UV exposure begins to degrade collagen and elastin fibers, leading to early rhytids (wrinkles) and dyspigmentation (lentigines), so wear your sunscreen. Consequently, the primary clinical implication for this demographic is prevention, specifically photoprotection and rigorous surveillance for malignant neoplasms using the ABCDE criteria (Asymmetry, Border, Color, Diameter, Evolving).

The Geriatric Population

The aging process results in the generalized atrophy of integumentary structures, leading to a compromised barrier and delayed healing. Structural integrity is lost due to dermal atrophy, where a reduction in collagen synthesis leads to a loss of tensile strength. Crucially, the flattening of rete ridges at the dermo-epidermal junction reduces the surface area for nutrient transfer and adhesion, making the skin highly susceptible to shearing forces and skin tears. This is compounded by subcutaneous wasting, or the loss of adipose tissue, which reduces shock absorption and thermal insulation.

Functional changes include xerosis (chronic dryness) due to the atrophy of sebaceous glands and sensory neuropathy, where a decrease in Pacinian and Meissner corpuscles raises the threshold for pain perception. These factors create a high risk for Decubitus ulcers (pressure injuries) due to tissue ischemia, mandating the use of lift sheets and frequent repositioning.

| Developmental Stage | Physiological Features | Nursing Implications |

| 1. Infants | • Thinner Skin: High water content and permeability; ineffective at retaining moisture or regulating heat. • Transient Features: Presence of vernix caseosa (coating), lanugo (hair), and milia. • Physiologic Jaundice: Yellowing due to immature liver function (resolves in 1–2 weeks). | • Gentle Handling: Use pH-neutral cleansers; avoid vigorous scrubbing. • Protection: maintain warmth to prevent heat loss; use gentle adhesives to prevent tears. • Product Safety: Avoid perfumes/additives due to rapid absorption risks. |

| 2. Children | • Maturation: Stratum corneum thickens and becomes more elastic/resilient. • High Surface Area: Ratio to body volume remains high (absorption risk persists). • Dormant Glands: Sweat/oil glands are relatively inactive, leading to drier skin. | • Injury Management: Manage frequent scrapes/cuts; ensure tetanus prophylaxis. • Psychological Support: Address fear of pain/mutilation using distraction and gentle techniques. |

| 3. Adolescents | • Hormonal Surge: Androgens trigger glandular activity. • Glandular Activity: Sebaceous glands enlarge (acne/oil); apocrine glands activate (body odor). • Hair Growth: Terminal hair develops in axillary, pubic, and facial areas. | • Hygiene Education: Teach cleansing routines and deodorant use. • Acne Management: Educate on appropriate treatments and avoiding picking to prevent scarring. • Sun Safety: Counseling on long-term damage prevention. |

| 4. Adults | • Peak Stability: Epidermis/dermis fully thickened; steady gland activity. • Early Aging: Photoaging and collagen decline begin in 30s/40s (fine lines/pigmentation). • Conditions: Potential for adult-onset acne, rosacea, or melasma (pregnancy). | • Maintenance: Focus on prevention (hydration, nutrition, smoking cessation, sun protection). • Surveillance: Encourage regular self-exams for suspicious lesions. |

| 5. Older Adults | • Thinning: Loss of subcutaneous fat (less insulation) and dermis. • Loss of Elasticity: Collagen breakdown leads to wrinkles/sagging. • Xerosis: Reduced gland activity causes dryness. • Sensory Decline: Reduced nerve endings increase injury risk. | • Injury Prevention: Use lift sheets to prevent shearing; minimize tape. • Pressure Ulcer Prevention: Regular turning and cushioning. • Care Routine: Bathe less frequently; moisturize damp skin. • Temp Control: Monitor for hypothermia/overheating. |

See also

Craving more insights? Dive into these related materials to enhance your study journey!

- Anatomy and Physiology Nursing Test Banks. This nursing test bank includes questions about Anatomy and Physiology and its related concepts such as: structure and functions of the human body, nursing care management of patients with conditions related to the different body systems.

Leave a Comment