Learn about the nursing care management for patients with bacterial meningitis.

Table of Contents

- What is Bacterial Meningitis?

- Pathophysiology

- Causes

- Clinical Manifestations

- Prevention

- Complications

- Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

- Medical Management

- Nursing Management

- See Also

What is Bacterial Meningitis?

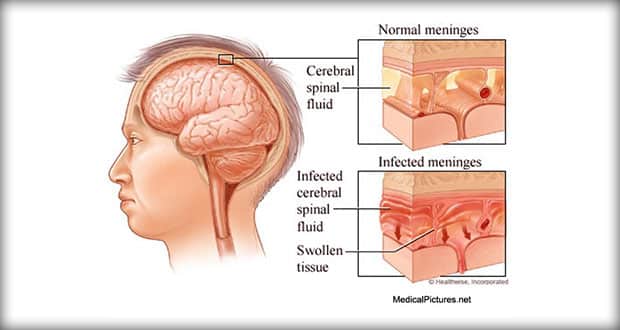

Meningitis is one of the infectious disorders of the nervous system.

- Meningitis is an inflammation of the lining around the brain and spinal cord caused by bacteria or viruses.

- Bacterial meningitis is caused by bacteria.

- Meningitis can be the primary reason a patient is hospitalized or can develop during hospitalization.

Pathophysiology

Meningeal infections generally originate in two ways: through the bloodstream or direct spread.

- Transmission. N. meningitidis concentrates in the nasopharynx and is transmitted by secretion or aerosol contamination.

- Entry. One of the causative organism enters the bloodstream, it crosses the blood brain barrier and proliferates in the cerebrospinal fluid.

- Stimulation. The host immune system stimulates the release of cell wall fragments and lipopolysaccharides, facilitating inflammation of the subarachnoid and pia mater.

- Increased ICP. Because the cranial vault contains little room for expansion, the inflammation may cause increased intracranial pressure.

- Circulation. CSF circulates through the subarachnoid space, where inflammatory cellular materials from the affected meningeal tissue enter and accumulate.

Causes

Factors that may cause bacterial meningitis include:

- Tobacco use. Tobacco use predisposes the patient to meningitis.

- Viral upper respiratory infection. Viral upper respiratory infection increase the amount of droplet production.

- Otitis media. Otitis media increase the risk of bacterial meningitis because the bacteria can cross the epithelial membrane and enter the subarachnoid space.

- Immune system deficiency. People with immune system deficiencies are also at greater risk for development of bacterial meningitis.

- Bacteria. The bacteria Streptococcus pneumoniae and Neisseria meningitides are responsible for 80% of cases of meningitis in adults, as well as Haemophilus influenzae in children.

Clinical Manifestations

Headache and fever are frequently the initial symptoms.

- Headache. The headache is usually steady or throbbing and very severe as a result of meningeal irritation.

- Neck mobility. A stiff and painful neck can be an early sign and any attempts at flexion of the head are difficult.

- Positive Kernig’s sign. When the patient is lying with the thigh flexed on the abdomen, the leg cannot be completely extended.

- Positive Brudzinski’s sign. When the patient’s neck is flexed, flexion of the knees and hips is produced; when the lower extremity of one side is passively flexed, a similar movement is seen in the opposite extremity.

- Photophobia. Extreme sensitivity to light is a common finding.

- Skin lesions. Skin lesions develop, ranging from a petechial rash with purpuric lesions to large areas of ecchymosis.

- Cognitive impairment. Disorientation and memory impairment are common early in the course of the illness.

- Seizures. Seizures can occur and are the result of areas of irritability in the brain.

Prevention

The prevention of bacterial meningitis includes:

- Vaccine. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that the meningococcal conjugated vaccine be given to adolescents entering high school and to college freshmen living in dormitories.

- Health education. Most states mandate education addressing meningococcal meningitis.

- Antimicrobial prophylaxis. People in close contact with patients with meningococcal meningitis should be treated with antimicrobial chemoprophylaxis using rifampin, ciprofloxacin, or ceftriaxone sodium.

Complications

Complications of patients with bacterial meningitis include:

- Visual impairment. Infection may spread towards the eyes if left untreated.

- Deafness. Deafness may also occur when the bacteria reaches the optic nerve.

- Seizures. The bacteria irritates the meningeal layers and may lead to seizures.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

If the clinical presentation suggests meningitis, diagnostic testing is conducted to identify the causative organism.

- Computed tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan to detect a shift in brain contents (which may lead to herniation) prior to a lumbar puncture.

- Key diagnostic tests: bacterial culture and Gram staining of CSF and blood.

- Diagnosis is made by lumbar puncture. The CSF is cloudy. Gram stain of the CSF reveals organisms in 70% to 80% of all cases. When the organisms cannot be identified, bacterial antigens can be determined. H. influenzae is frequently detected with this technique. Clients with bacterial meningitis demonstrate the following:

- Moderately elevated CSF pressures

- Elevated CSF protein level (normal, 15 to 45 mg/dl)

- Decreased CSF glucose level (normal, 60 to 80 mg/dl, or two thirds of the serum glucose value)

- Elevated white blood cell count, usually increased (100 to 10, 000/cm3), with predominantly polymorphonuclear leukocytes.

- Medical diagnosis is made by assessment of clinical manifestations and is confirmed by isolating the causative organism from the CSF.

Medical Management

Bacterial meningitis constitutes a medical emergency. Prognosis varies according to the causative organism. The use of antibiotics has reduced the death rate to less than 5% for all types of bacterial meningitis. If untreated, it can be fatal within hours to days. Deaths most often occur in newborn infants and in older adults. Complications are rate but may include septic shock, vasomotor collapse, seizures, and increased ICP attributable to hydrocephalus, brain swelling, and fluid overload. Residual neurologic deficits are rare in adults.

A unique problem in treating CNS infection is that [highlight]an intact blood-brain barrier prevents complete penetration of the antibiotic[/highlight]. However, inflammation inhibits the blood-brain barrier, so for short time antibiotics penetrate the CNS. Antibiotics are given intravenously; the blood-brain barrier recovers as inflammation subsides, and high doses are required to reach the CSF.

- Adequate fluid and electrolyte balance must be maintained. Frequent assessment of the neurologic status is indicated to detect early manifestations of increasing ICP and seizures. Anticonvulsants may be prescribed for seizure prevention.

- Antibiotic therapy. Early administration of an antibiotic that crosses the blood brain barrier into the subarachnoid space in sufficient concentration to halt the multiplication of bacteria like Vancomycin administered intravenously.

- Corticosteroids. Dexamethasone has been shown to be beneficial as adjunct therapy in the treatment of bacterial meningitis if it is administered 15 to 20 minutes before the first dose of antibiotic and every 6 hours for the next 4 days.

- Fluid volume expanders. Dehydration and shock are treated with fluid volume expanders.

Nursing Management

The patient with meningitis is critically ill; therefore many of the nursing interventions are collaborative with the physician, respiratory therapist, and other members of the healthcare team.

Nursing Assessment

Assessment of the patient with bacterial meningitis include.

- Neurologic status. Neurologic status and vital signs are continually assessed.

- Pulse oximetry and arterial blood gas values. These values are used to quickly identify the need for respiratory support.

Nursing Diagnosis

Based on the assessment data, major nursing diagnoses include:

- Risk for Infection Transmission related to contagious nature of organism

- Acute Pain related to headache, fever, neck pain secondary to meningeal irritaiton

- Acute Pain related to nuchal rigidity, muscle aches, immobility and increased sensitivity to external stimuli secondary to infectious process

- Impaired Physical Mobility related to intravenous infusion, nuchal rigidity and restraining devices

- Activity Intolerance related to fatigue and malaise secondary to infection

- Risk for Impaired Skin Integrity related to immobility, dehydration, and diaphoresis

- Risk for Injury related to restlessness and disorientation secondary to meningeal irritation

- Interrupted Family Process related to critical nature of situation and uncertain prognosis

- Anxiety related to treatment and risk of death

- Risk for Ineffective Therapeutic Regimen Management

Nursing Care Planning & Goals

Goals for a patient with bacterial meningitis include:

- Protection against injury.

- Prevention of infection.

- Restoring normal cognitive functions.

- Prevention of complications.

Nursing Interventions

Important components of nursing care include the following measures:

- Assess neurologic status and vital signs constantly. Determine oxygenation from arterial blood gas values and pulse oximetry.

- Insert cuffed endotracheal tube (or tracheostomy), and position patient on mechanical ventilation as prescribed.

- Assess blood pressure (usually monitored using an arterial line) for incipient shock, which precedes cardiac or respiratory failure.

- Rapid IV fluid replacement may be prescribed, but take care not to overhydrate patient because of risk of cerebral edema.

- Reduce high fever to decrease load on heart and brain from oxygen demands.

- Protect the patient from injury secondary to seizure activity or altered level of consciousness (LOC).

- Monitor daily body weight; serum electrolytes; and urine volume, specific gravity, and osmolality, especially if syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) is suspected.

- Prevent complications associated with immobility, such as pressure ulcers and pneumonia.

- Institute infection control precautions until 24 hours after initiation of antibiotic therapy (oral and nasal discharge is considered infectious).

- Inform family about patient’s condition and permit family to see patient at appropriate intervals.

Evaluation

Expected patient outcomes include:

- Avoidance of injury.

- Avoidance of infection.

- Restoration of normal cognitive functions.

- Prevention of complications.

Discharge and Home Care Guidelines

After hospitalization, the patient at home should:

- Activities. Alternate rest and activity to conserve energy.

- Diet. Consume safe, clean, and healthy foods.

- Asepsis. Promote simple infection control procedures at home.

- Infectious process. Identify signs and symptoms of an infectious process and report to the physician promptly.

Documentation Guidelines

The focus of documentation in patients with bacterial meningitis are:

- Client’s description of response to pain.

- Acceptable level of pain.

- Prior medication use.

- Current physical findings.

- Client’s understanding of individual risks and safety concerns.

- Availability and use of resources.

- Current and previous level of function.

- Effect on independence and lifestyle.

- Results of laboratory and diagnostic tests.

- Mental status pr cognitive evaluation results.

- Plan of care.

- Teaching plan.

- Response to interventions, teaching, and actions performed.

- Attainment or progress towards desired outcomes.

- Modifications to plan of care

See Also

Posts related to this care plan: