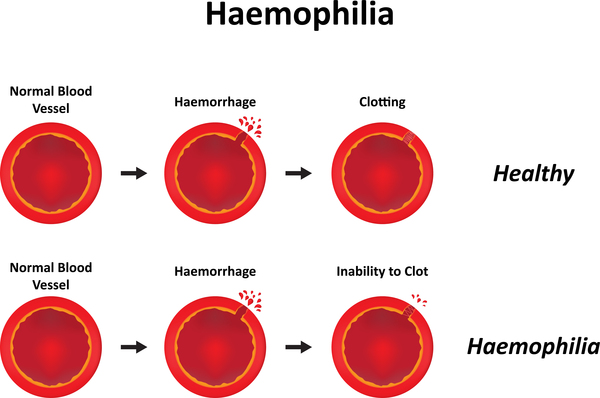

Hemophilia is a rare but significant genetic bleeding disorder that affects the blood‘s ability to clot properly, leading to prolonged and potentially life-threatening bleeding episodes. Hemophilia primarily affects males, and its severity can vary depending on the level of clotting factors in the blood.

This nursing note aims to provide an overview of hemophilia from a nursing perspective, emphasizing the importance of individualized care, patient education, and a multidisciplinary approach in handling individuals living with this complex bleeding disorder.

What is Hemophilia?

Hemophilia is now on the rise among the pediatric population across the world.

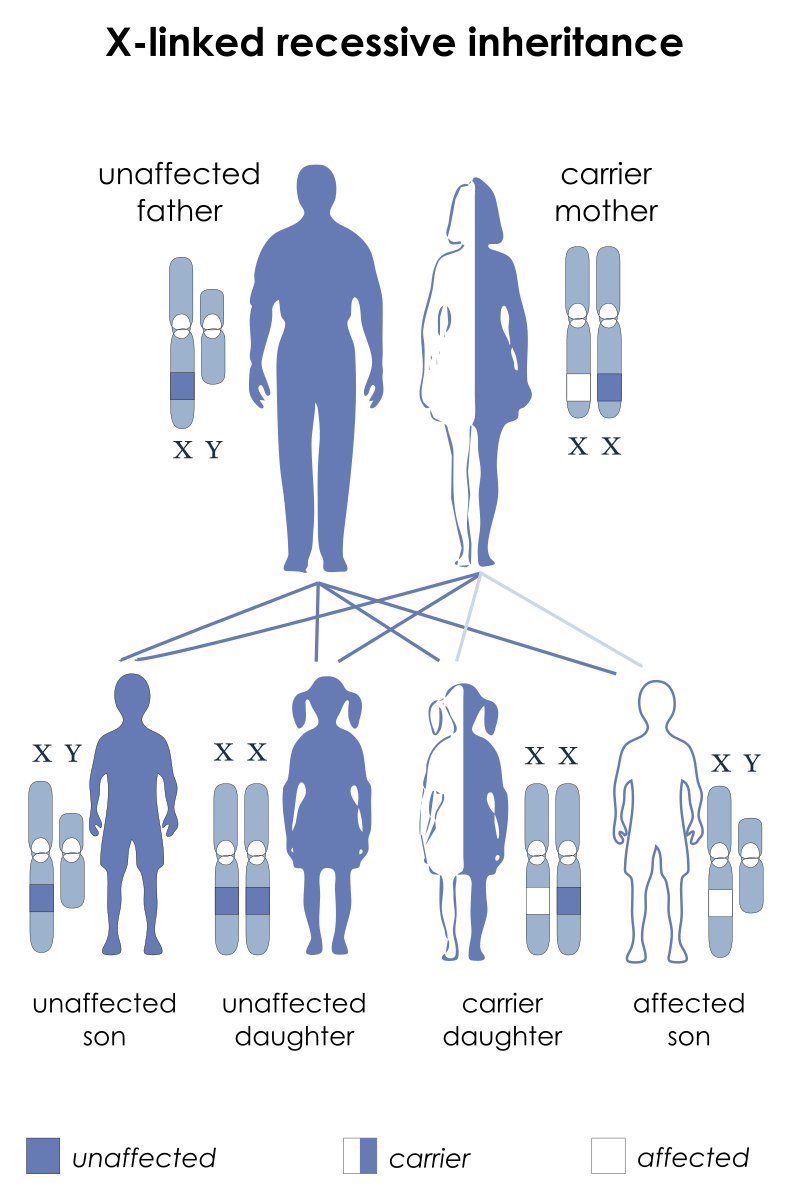

- Hemophilia results from mutations at the factor VIII or IX loci on the X chromosome and each occurs in mild, moderate, and severe forms.

- A similar level of deficiency of factor VIII or IX results in clinically indistinguishable disease because the end result is deficient activation of factor X by the factor Xase complex (FVIIIa/FIXa/calcium and phospholipid).

- Hemophilia A is an X-linked, recessive disorder caused by the deficiency of functional plasma clotting factor VIII (FVIII), which may be inherited or arise from spontaneous mutation.

- Hemophilia B, or Christmas disease, is an inherited, X-linked, recessive disorder that results in the deficiency of functional plasma coagulation factor IX.

Pathophysiology

Pathophysiologies for both hemophilia A and B are as follows:

- Primary sites of factor VIII (FVIII) production are thought to be the vascular endothelium in the liver and the reticuloendothelial system.

- FVIII deficiency, dysfunctional FVIII, or FVIII inhibitors lead to the disruption of the normal intrinsic coagulation cascade, resulting in excessive hemorrhage in response to trauma and, in severe cases, spontaneous hemorrhage.

- Human synovial cells synthesize high levels of tissue factor pathway inhibitor, resulting in a higher degree of factor Xa (FXa) inhibition, which predisposes hemophilic joints to bleed.

- This effect may also account for the dramatic response of activated factor VII (FVIIa) infusions in patients with acute hemarthroses and FVIII inhibitors.

- Bleeding into a joint may lead to synovial inflammation, which predisposes the joint to further bleeds; a joint that has had repeated bleeds (by one definition, at least 4 bleeds within a 6-month period) is termed a target joint.

- Approximately 30% of patients with severe hemophilia A develop alloantibody inhibitors that can bind FVIII; these inhibitors are typically immunoglobulin G (IgG), predominantly of the IgG4 subclass, that neutralizes the coagulant effects of replacement therapy.

- Factor IX deficiency, dysfunctional factor IX, or factor IX inhibitors lead to disruption of the normal intrinsic coagulation cascade, resulting in spontaneous hemorrhage and/or excessive hemorrhage in response to trauma.

- Hemorrhage sites include joints (eg, knee, elbow), muscles, central nervous system (CNS), GI system, genitourinary (GU) system, pulmonary system, and cardiovascular system.

- Factor IX, a vitamin K–dependent single-chain glycoprotein, is synthesized first by the hepatocyte; the precursor protein undergoes extensive posttranslational modification before being secreted into the blood.

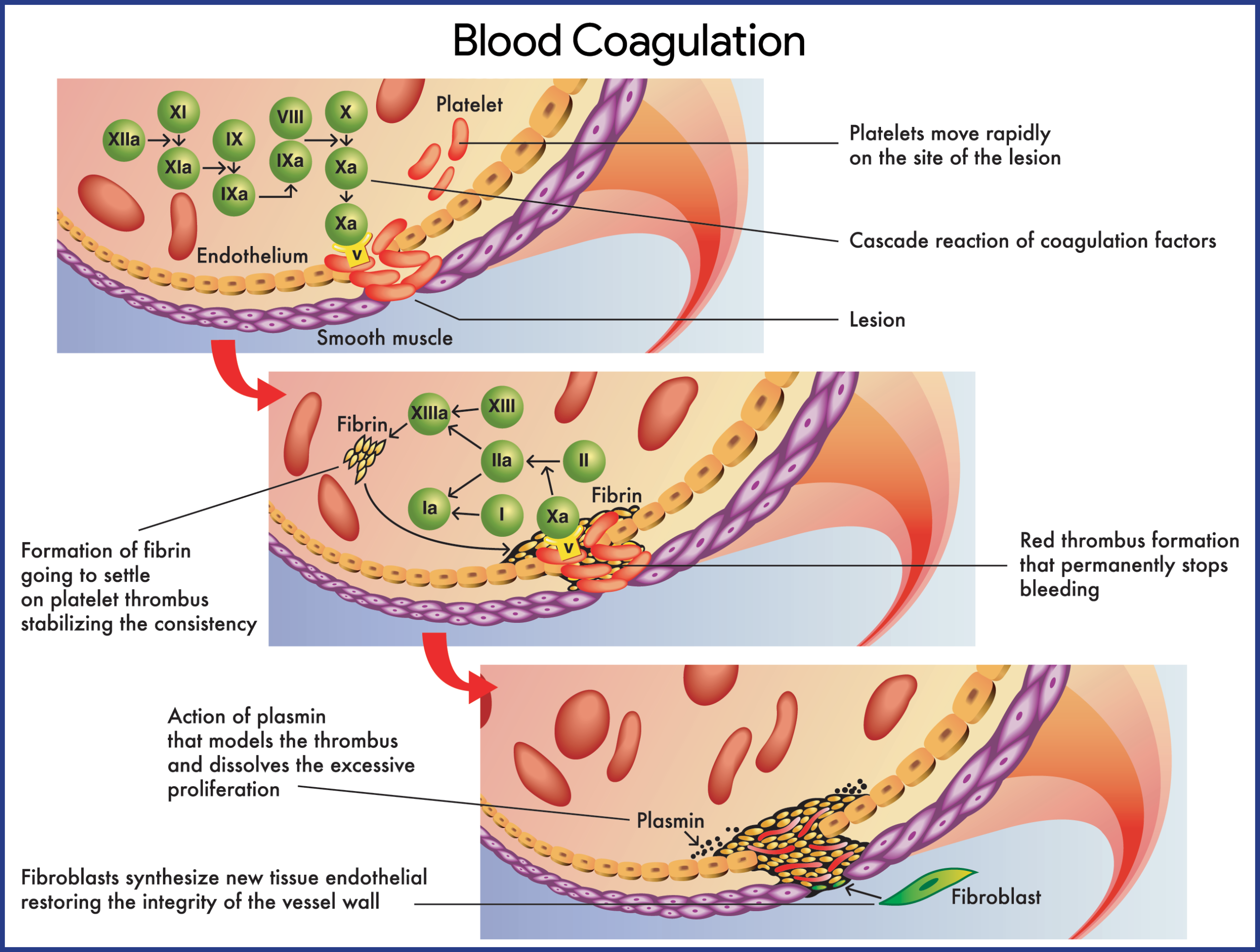

- The intrinsic system is initiated when factor XII is activated by contact with damaged endothelium.

- In the extrinsic system, the conversion of factor X to factor Xa involves tissue factor (TF), or thromboplastin; factor VII; and calcium ions.

- FVIII and FIX circulate in an inactive form; when activated, these 2 factors cooperate to cleave and activate factor X, a key enzyme that controls the conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin.

- Therefore, the lack of either of these factors may significantly impair clot formation and, as a consequence, result in clinical bleeding.

Statistics and Incidences

Hemophilia is slowly progressing among pediatric patients in all parts of the globe.

- Hemophilia A is the most common X-linked genetic disease and the second most common factor deficiency after von Willebrand disease (vWD).

- The worldwide incidence of hemophilia A is approximately 1 case per 5000 males, with approximately one-third of affected individuals not having a family history of the disorder.

- In the United States, the prevalence of hemophilia A is 20.6 cases per 100,000 males; in 2016, the number of people in the United States with hemophilia was estimated to be about 20,000.

- Hemophilia A occurs in all races and ethnic groups.

- Because hemophilia is an X-linked, recessive condition, it occurs predominantly in males; females usually are asymptomatic carriers.

- The incidence of hemophilia B is estimated to be approximately 1 case per 25,000-30,000 male births.

- The prevalence of hemophilia B is 5.3 cases per 100,000 male individuals, with 44% of those having severe disease.

- Hemophilia B is much less common than hemophilia A. Of all hemophilia cases, 80-85% are hemophilia A, 14% are hemophilia B, and the remainder are various other clotting abnormalities.

- Hemophilia B occurs in all races and ethnic groups.

Causes

The causes of both hemophilia A and B are apparently from a genetic form.

- Genetics. Hemophilia A is caused by an inherited or acquired a genetic mutation that results in dysfunction or deficiency of factor VIII, or by an acquired inhibitor that binds factor VIII; Hemophilia B is an X-linked recessive disease caused by an inherited or acquired mutation in the factor IX gene or by an acquired factor IX inhibitor.

Clinical Manifestations

Hemophilia is suggested by a history of hemorrhage disproportionate to trauma or of spontaneous hemorrhage, or a family history of bleeding problems.

- Spontaneous hemorrhage. Approximately 30-50% of patients with severe hemophilia present with manifestations of neonatal bleeding (eg, after circumcision); other neonates may present with severe hematoma and prolonged bleeding from the cord or umbilical area or at sites of blood draws or immunizations.

- Hematuria. In the genitourinary tract, gross hematuria may occur in as many as 90% of patients.

- General symptoms. Weakness and orthostasis may occur.

- Musculoskeletal. Tingling, cracking, warmth, pain, stiffness, and refusal to use the joint among children are common.

- Central nervous system. Headache, stiff neck, vomiting, lethargy, irritability, and spinal cord syndromes may occur.

- Genitourinary. Symptoms may be painless; there may be hepatic/splenic tenderness and peritoneal signs.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

The diagnosis of hemophilia A and B is established by measuring the following:

- Chromogenic assay. This assay is considered by some to be more accurate, as it measures the level of plasma factor VIII activity but it is less widely available in clinical laboratories in the United States.

- Laboratory studies. Laboratory studies for suspected hemophilia include a complete blood cell count, coagulation studies, and a factor VIII (FVIII) assay.

- CT scans. Head CT scans without contrast are used to assess for spontaneous or traumatic intracranial hemorrhage.

- MRI. Perform magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) on the head and spinal column for further assessment of spontaneous or traumatic hemorrhage; MRI is also useful in the evaluation of the cartilage, synovium, and joint space.

- Ultrasonography. Ultrasonography is useful in the evaluation of joints affected by acute or chronic effusions.

- Testing for inhibitors. Laboratory confirmation of a FVIII inhibitor is clinically important when a bleeding episode is not controlled despite the infusion of adequate amounts of factor concentrate.

- Carrier testing. Screening for carrier status can be performed by measuring the ratio of FVIII coagulant activity to the concentration of von Willebrand factor (vWF) antigen; a ratio that is less than 0.7 suggests carrier status.

- Radiography. Radiography for joint assessment is of limited value in acute hemarthrosis; evidence of chronic degenerative joint disease may be visible on radiographs in patients who have been untreated or inadequately treated or in those with recurrent joint hemorrhages.

Medical Management

The treatment of hemophilia may involve prophylaxis, management of bleeding episodes, treatment of factor VIII (FVIII) inhibitors, and treatment and rehabilitation of hemophilia synovitis.

- Prehospital care. Rapid transport to definitive care is the mainstay of prehospital care; prehospital care providers should apply aggressive hemostatic techniques, assist patients capable of self-administered factor therapy, and gather focused historical data if the patient is unable to communicate.

- Emergency department care. Use aggressive hemostatic techniques; correct coagulopathy immediately; include a diagnostic workup for hemorrhage, but never delay indicated coagulation correction pending diagnostic testing; acute joint bleeding and expanding, large hematomas require adequate factor replacement for a prolonged period until the bleed begins to resolve, as evidenced by clinical and/or objective methods; life-threatening bleeding episodes are generally initially treated with FVIII levels of approximately 100%, until the clinical situation warrants a gradual reduction in dosage.

- Factor VIII and FIX concentrates. Various FVIII and FIX concentrates are available to treat hemophilia A and B; besides improved hemostasis, continuous infusion decreases the amount of factor used, which can result in significant savings; obtain factor level assays daily before each infusion to establish a stable pattern of replacement regarding the dose and frequency of administration.

- Desmopressin. Desmopressin vasopressin analog, or 1-deamino-8-D-arginine vasopressin (DDAVP), is considered the treatment of choice for mild and moderate hemophilia A; DDAVP stimulates a transient increase in plasma FVIII levels; DDAVP may result in sufficient hemostasis to stop a bleeding episode or to prepare patients for dental and minor surgical procedures.

- Management of bleeding. Immobilization of the affected limb and the application of ice packs are helpful in diminishing swelling and pain; early infusion upon the recognition of initial symptoms of a joint bleed may often eliminate the need for a second infusion by preventing the inflammatory reaction in the joint; prompt and adequate replacement therapy is the key to preventing long-term complications.

- Treatment of patients with inhibitors. Inhibitors are antibodies that neutralize factor VIII (FVIII) and can render replacement therapy ineffective; the treatment of patients with inhibitors of FVIII is difficult; assuming no anamnestic response, low-titer inhibitors (ie, concentrations below 5 Bethesda units [BU]) occasionally can be overcome with high doses of factor VIII; there is no established treatment for bleeding episodes in patients with high-titer inhibitors.

- Prophylactic factor infusions. The main goal of prophylactic treatment is to prevent bleeding symptoms and organ damage, in particular to joints; in December 2013, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) expanded the indication for anti-inhibitor coagulant complex (Feiba NF) to include routine prophylaxis in patients with hemophilia A or B who have developed inhibitors; approval was based on data from a pivotal phase III study in which a prophylactic regimen resulted in a 72% reduction in median annual bleed rate compared with on-demand treatment.

- Pain management. Hemophilic chronic arthropathy is associated with pain; narcotic agents have been used, but frequent use of these drugs may result in addiction; nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may be used instead because their effects on platelet function are reversible and because these drugs can be effective in managing acute and chronic arthritic pain; avoid aspirin because of its irreversible effect on platelet function.

- Activity. Generally, individuals with severe hemophilia should avoid high-impact contact sports and other activities with a significant risk of trauma; however, mounting evidence suggests that appropriate physical activity improves overall conditioning, reduces injury rate and severity, and improves psychosocial functioning.

- Gene therapy. With the cloning of FVIII and advances in molecular technologies, the possibility of a cure for hemophilia with gene therapy was conceived; ex vivo gene therapy, in which cells to be transplanted are genetically modified to secrete factor VIII and then are reimplanted into the recipient; in vivo gene therapy, in which a vector (typically a virus altered to include FVIII DNA) is directly injected into the patient; and nonautologous gene therapy, in which cells modified to secrete FVIII are packaged in immunoprotected devices and implanted into recipients.

- Radiosynovectomy. In patients who develop synovitis from joint bleeds, intra-articular injection of radioisotopes to ablate the synovium (radiosynovectomy) can be used to decrease bleeding, slow the progression of cartilage and bone damage, and prevent arthropathy.

Pharmacologic Management

Medications of choice for patients with hemophilia are:

- Factor VIII. Factor VIII (FVIII) is the treatment of choice for acute or potential hemorrhage in hemophilia A; recombinant FVIII concentrate is generally the preferred source of factor VIII; prophylactic administration of FVIII is often recommended for pediatric patients with severe disease.

- Antifibrinolytic agents. Antifibrinolytic agents, such as aminocaproic acid and tranexamic acid, are especially useful for oral mucosal bleeds but are contraindicated as initial therapies for hemophilia-related hematuria originating from the upper urinary tract because they can cause obstructive uropathy or anuria.

- Factor IX. Factor IX is the treatment of choice for acute hemorrhage or presumed acute hemorrhage in hemophilia B. Recombinant factor IX is the preferred source for replacement therapy.

- Coagulation factor VIIa. These agents can activate coagulation factor X to factor Xa as well as coagulation factor IX to IXa.

- Coagulation factors. FVIII concentrates replace deficient FVIII in patients with hemophilia A, with the goal of achieving a normal hematologic response to hemorrhage or preventing hemorrhage; recombinant products should be used initially and subsequently in all newly diagnosed cases of hemophilia that require factor replacement; agents that bypass FVIII activity in the clotting cascade (eg, activated FVII) are used in patients with FVIII inhibitors.

- Antihemophilic agents. These agents are used to control bleeding in hemophilia B or FIX deficiency and to prevent and/or control bleeding in patients with hemophilia A and inhibitors to FVIII.

- Monoclonal antibodies. Monoclonal antibodies are used to bind to one specific substance in the body (eg, molecules, antigens); this binding is very versatile and can mimic, block, or cause changes to enact precise mechanisms (eg, bridging molecules, replacing or activating enzymes or cofactors, immune system stimulation).

- Vasopressin-related. Desmopressin transiently increases the FVIII plasma level in patients with mild hemophilia A.

Nursing Management

Nursing care for a child with hemophilia includes:

Nursing Assessment

Assessment in a child with hemophilia includes the following:

- History. For patients in whom hemophilia is suspected, inquire about the history of hemorrhage disproportionate to trauma, history of spontaneous hemorrhage, bleeding disorders in the family, and concomitant illness (especially those associated with acquired hemophilia, such as chronic inflammatory disorders, autoimmune diseases, hematologic malignancies, and allergic drug reactions).

- Physical examination. Assess for joint swelling and ability to move an affected limb; Assess for limited ROM, contractures, and bony changes in the joints when bleeding has stopped.

Nursing Diagnoses

Based on the assessment data, the major nursing diagnoses are:

- Acute pain related to traumatic injury to the muscles.

- Impaired physical injury related pain and discomfort with the onset of bleeding episodes.

- Compromised family coping related to incorrect and inadequate information or understanding.

- Risk for bleeding related to decreased concentration of clotting factors circulating in the blood (factor VIII and factor IX).

- Risk for injury related to decreased clotting factor (VIII or IX).

Nursing Care Planning and Goals

Main Article 5 Hemophilia Nursing Care Plans

The major goals are:

- Child will experience decreased pain.

- Child will maintain optimal physical mobility as evidenced by normal range of motion (ROM) and activities of daily living within ability.

- Family will cope effectively with child’s illness.

- Child’s risk for injury from possible bleeding is decreased through the use of appropriate prophylactic measures.

Nursing Interventions

The nursing interventions for a child with hemophilia are:

- Relieve pain. Immobilize joints and apply elastic bandages to the affected joint if indicated; elevate affected and apply a cold compress to active bleeding sites, but must be used cautiously in young children to prevent skin breakdown.

- Maintain optimal physical mobility. Provide gentle, passive ROM exercise when the child’s condition is stable; educate on preventive measures, such as the application of protective gear and the administration of factor products; and refer for physical therapy, occupational therapy, and orthopedic consultations, as required.

- Assist in the coping of the family. Encourage family members to verbalize problem areas and develop solutions on their own; encourage family members to express

feelings, such as how they deal with the chronic needs of a family member and coping patterns that help or hinder adjustment to the problems. - Prevent bleeding. Monitor hemoglobin and hematocrit levels; assess for inhibitor antibody to factor VIII; anticipate or instruct in the need for prophylactic treatment before high-risk situations, such as invasive diagnostic or surgical procedures, or dental work; and provide replacement therapy of deficient clotting factors.

- Prevent injury. Utilize appropriate toys (soft, not pointed

or small sharp objects); for infants, may need to use padded bed rail sides on crib; avoid rectal temperatures; provide appropriate oral hygiene (use of

a water irrigating device; use of a soft toothbrush or soften the toothbrush with warm water before brushing; use of sponge-tipped toothbrush); and avoid contact sports such as football, soccer, ice hockey, and karate.

Evaluation

Goals are met as evidenced by:

- Child experienced decreased pain.

- Child maintained optimal physical mobility as evidenced by normal range of motion (ROM) and activities of daily living within the ability.

- Family coped effectively with the child’s illness.

- Child’s risk for injury from possible bleeding was decreased through the use of appropriate prophylactic measures.

Documentation Guidelines

Documentation in a child with hemophilia includes the following:

- Baseline and subsequent assessment findings to include signs and symptoms.

- Individual cultural or religious restrictions and personal preferences.

- Plan of care and persons involved.

- Teaching plan.

- Client’s responses to teachings, interventions, and actions performed.

- Attainment or progress toward the desired outcome.

- Long-term needs, and who is responsible for actions to be taken.

Leave a Comment