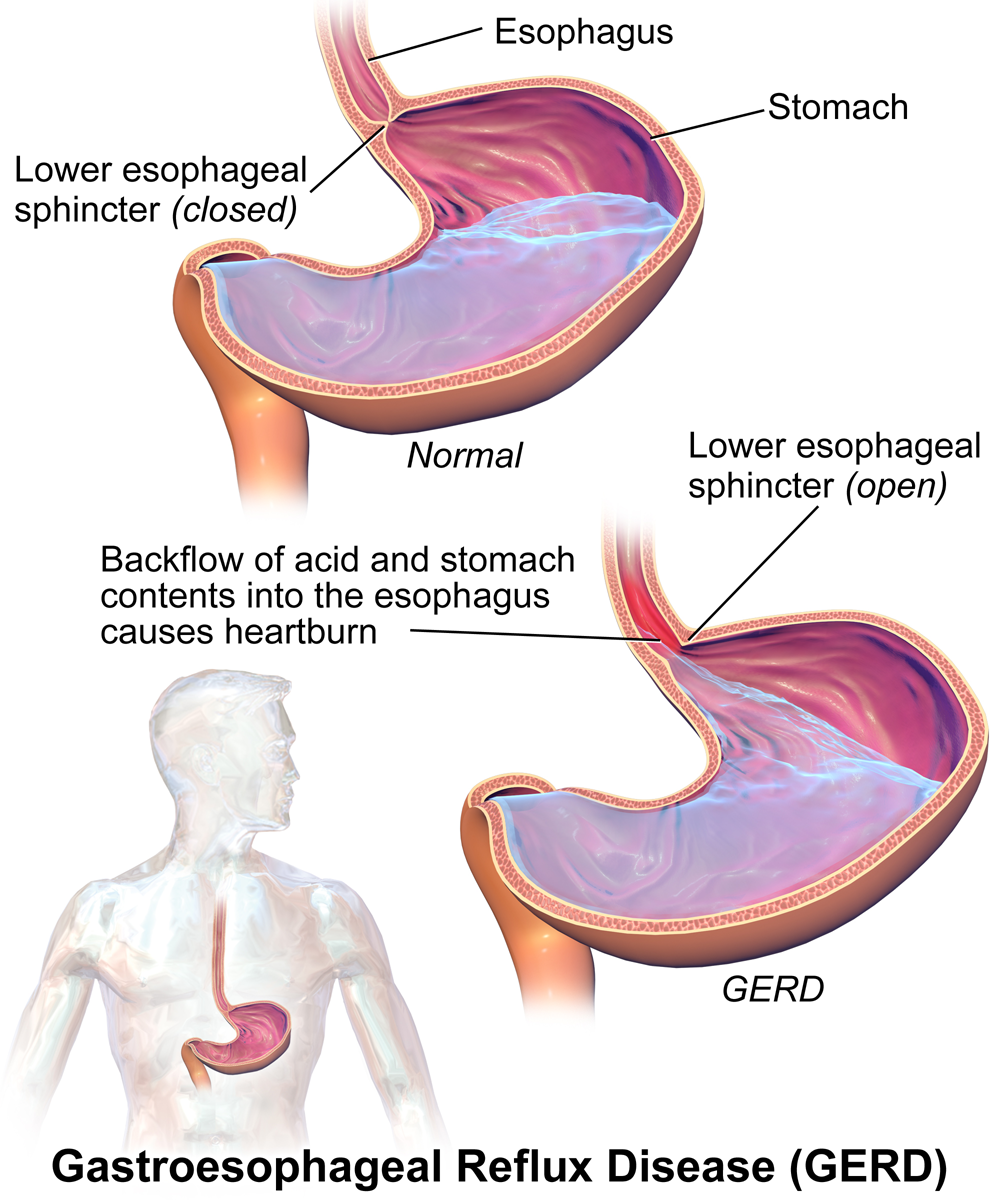

Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) is a common and often benign condition that affects people of all ages. It occurs when stomach contents, including acid and digestive enzymes, flow backward into the esophagus, causing symptoms like heartburn and regurgitation. While occasional GER is normal, persistent or severe reflux can lead to gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and may require medical intervention.

This article aims to serve as a comprehensive nursing guide to gastroesophageal reflux, emphasizing the significance of patient education, preventive strategies, and a patient-centered approach.

What is Gastroesophageal Reflux?

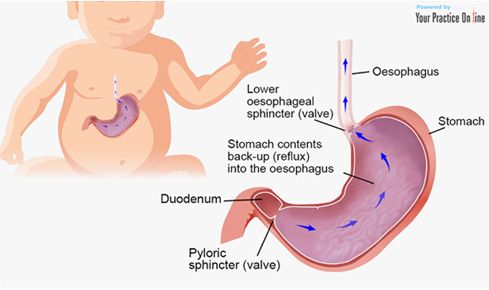

- In pediatric gastroesophageal reflux, immaturity of lower esophageal sphincter (LES) function is manifested by frequent transient lower esophageal relaxations (tLESRs), which result in the retrograde flow of gastric contents into the esophagus.

- Thus, gastroesophageal reflux represents a common physiologic phenomenon in the first year of life; as many as 60-70% of infants experience emesis during at least 1 feeding per 24-hour period by age 3-4 months.

- The distinction between this “physiologic” gastroesophageal reflux and “pathologic” gastroesophageal reflux in infancy and childhood is determined not merely by the number and severity of reflux episodes (when assessed by intraesophageal pH monitoring), but also, and most importantly, by the presence of reflux-related complications, including failure to thrive, erosive esophagitis, esophageal stricture formation, and chronic respiratory disease.

Classification

Gastroesophageal reflux is classified as follows:

- Physiologic (or functional) gastroesophageal reflux. These patients have no underlying predisposing factors or conditions; growth and development are normal, and pharmacologic treatment is typically not necessary.

- Pathologic gastroesophageal reflux or gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Patients frequently experience some complications, requiring careful evaluation and treatment.

- Secondary gastroesophageal reflux. This refers to a case in which an underlying condition may predispose to gastroesophageal reflux; examples include asthma (a condition which may also be, in part, caused by or exacerbated by reflux) and gastric outlet obstruction.

Pathophysiology

Reflux after meals occurs in healthy persons; however, these episodes are generally transient and are accompanied by rapid esophageal clearance of refluxed acid.

- The angle of His (made by the esophagus and the axis of the stomach) is obtuse in newborns but decreases as infants develop; this ensures a more effective barrier against gastroesophageal reflux.

- The presence of a hiatal hernia may displace the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) into the thoracic cavity, where the lower intrathoracic pressure may facilitate gastroesophageal reflux; however, the presence of a hiatal hernia by itself does not predict gastroesophageal reflux, which means that many patients who have a hiatal hernia do not have gastroesophageal reflux.

- Resistance to gastric outflow raises intragastric pressure and leads to reflux and vomiting; examples include gastroparesis, gastric outlet obstruction, and pyloric stenosis.

Statistics and Incidences

Although minor degrees of gastroesophageal reflux are noted in children and adults, the degree and severity of reflux episodes are increased during infancy.

- Gastroesophageal reflux is most commonly seen in infancy, with a peak at age 1-4 months; however, it can be seen in children of all ages, even healthy teenagers.

- Approximately 85% of infants vomit during the first week of life, and 60-70% manifest clinical gastroesophageal reflux at age 3-4 months.

- Symptoms abate without treatment in 60% of infants by age 6 months, when these infants begin to assume an upright position and eat solid foods.

- Resolution of symptoms occurs in approximately 90% of infants by age 8-10 months.

Clinical Manifestations

The symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux are most often directly related to the consequences of emesis (e.g., poor weight gain) or result from exposure of the esophageal epithelium to the gastric contents.

- Heartburn. Heartburn is more common in adults, and children have a harder time describing this sensation; they usually will complain of a stomach ache or chest discomfort, particularly after meals.

- Dental problems. In toddlers and older children, excessive regurgitation may lead to significant dental problems caused by acid effects on tooth enamel.

- Esophagitis. Esophagitis may manifest as crying and irritability in the nonverbal infant.

- Failure to thrive. Failure to thrive can result from insufficient caloric intake secondary to repeated vomiting and nutrient losses from emesis.

- Regurgitation. Frequent regurgitation or vomiting after especially after meals occurs when there is a resistance to the gastric outflow.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

In most cases of gastroesophageal reflux, the diagnosis can be made from the history and physical examination.

- Manometry. This is becoming a more accessible tool for use in infants and children; it is used to assess esophageal motility and lower esophageal sphincter (LES) function.

- Esophagogastroduodenoscopy. This modality is useful in patients who are unresponsive to medical therapy; it allows for visualization of the mucosa for diagnosis of peptic ulcer disease, Helicobacter pylori infection, strictures, and peptic esophagitis.

- Histologic findings. Histologic signs of peptic esophagitis include basal cell hyperplasia, extended papillae, and mucosal eosinophils.

- Upper GI imaging series. Such studies are used to evaluate the anatomy of the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract, but contrast imaging is neither sensitive nor specific for gastroesophageal reflux.

- Gastric scintiscan. A gastric scintiscan study, using milk or formula that contains a small amount of technetium sulfur colloid, can assess gastric emptying and reveal reflux (although not the degree or severity of it).

- Esophagography. Esophagography, conducted under fluoroscopic control, may reveal the integrity of esophageal peristalsis; however, it should not be used to assess the degree and severity of gastroesophageal reflux.

- Intraesophageal pH probe monitoring. A continuous esophageal pH probe in the distal esophagus documents the severity and frequency of reflux.

- Intraluminal esophageal electrical impedance. Intraluminal esophageal electrical impedance (EEI) is useful for detecting both acid reflux and nonacid reflux by measuring retrograde flow in the esophagus.

Medical Management

Results of medical therapy are generally met with a better long-term response, leading to the elimination of antisecretory medications (when prescribed) during infancy.

- Positioning. Infants and children diagnosed with gastroesophageal reflux should avoid the seated or the supine position shortly after meals; prone positioning may be recommended for the patient, at least for the first postprandial hour; sleeping in the prone position has been demonstrated to decrease the frequency of gastroesophageal reflux.

- Dietary measures.

- Thickening an infant’s formula provides a therapeutic advantage against gastroesophageal reflux, particularly when excessive vomiting is associated with suboptimal weight gain; younger formula-fed infants may benefit from a pre-thickened, proprietary formula (e.g., Enfamil-AR; Mead-Johnson Nutritionals Inc, Evansville, IN);

- For breastfed infants. Aside from increasing feeding frequency, expressed breast milk may be thickened as described; in addition, early introduction of rice cereal feedings (at age three (3) months) may be attempted;

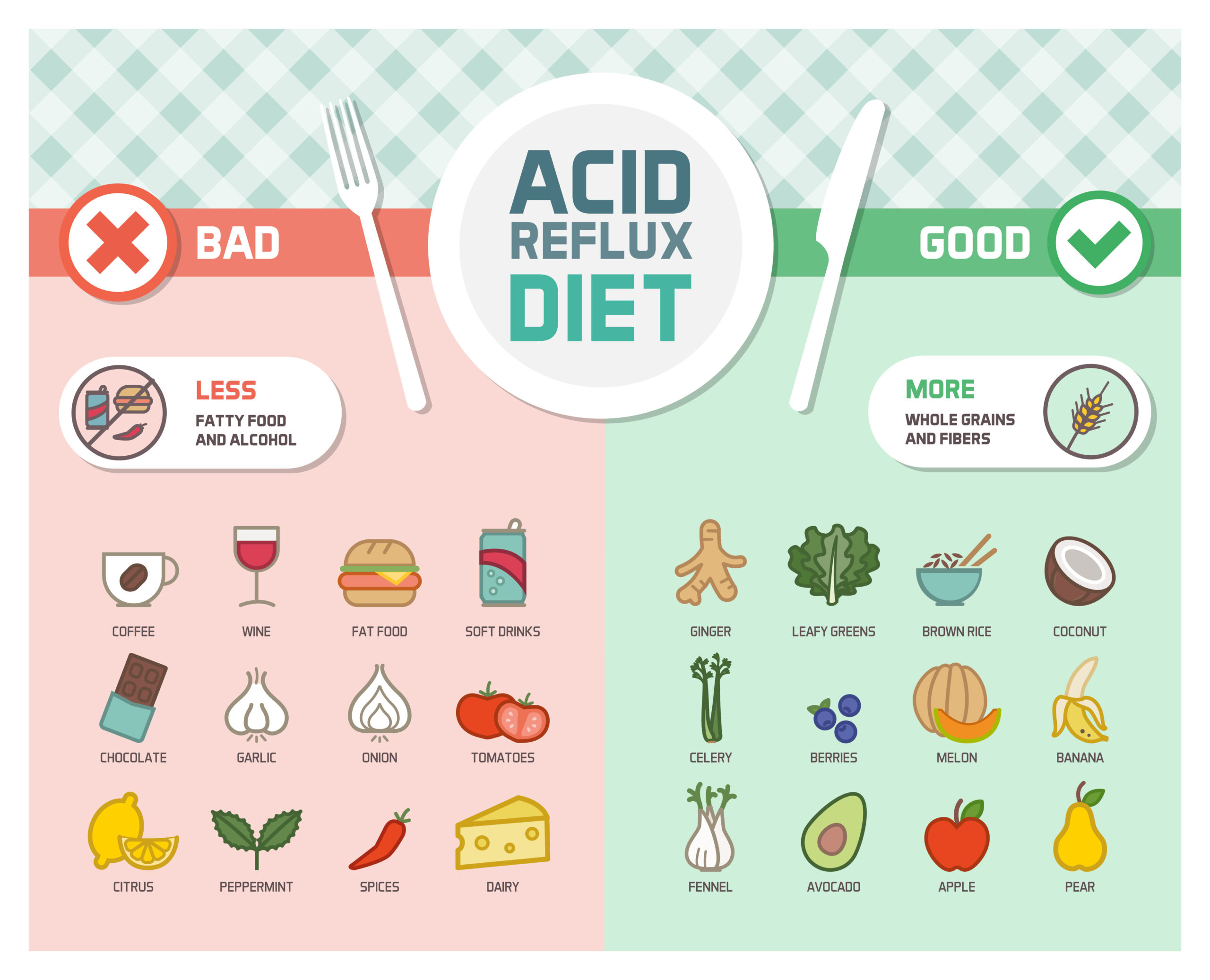

- For children. Small, frequent meals are also recommended; greasy and spicy foods, which encourage postprandial reflux by increasing gastric distention and slowing gastric emptying, should be avoided; chocolate, peppermint, tomato products, citrus, and caffeine, which lowers LES pressure, should also be avoided.

- Step-up and step-down therapy. Guidelines from the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) discuss the use of step-up and step-down therapies, which should be instituted under the guidance of a pediatric gastroenterologist; in the case of pharmacologic intervention, step-up therapy involves progression from diet and lifestyle changes to H2 -receptor blockade medications (eg, ranitidine, nizatidine) to proton pump inhibitors (eg, omeprazole, lansoprazole).

- Fundoplication. The goal of surgery for patients with GERD is to reestablish the antireflux barrier without creating an obstruction to the food bolus; in general, the Nissen fundoplication, which is a complete 360° wrap, best controls the symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux.

Pharmacologic Management

A therapeutic response to treatment for gastroesophageal reflux may take up to 2 weeks.

- Antacids. These agents are used as diagnostic tools to provide symptomatic relief in infants; associated benefits include symptomatic alleviation of constipation (aluminum antacids) or loose stools (magnesium antacids).

- Histamine H2 antagonists. Like antacids, these agents do not reduce the frequency of reflux but do decrease the amount of acid in the refluxate by inhibiting acid production; all H2 -receptor antagonists are equipotent when used in equivalent doses; they are most effective in patients with nonerosive esophagitis; H2 -receptor antagonists are considered the drugs of choice for children because pediatric doses are well established and the medications are available in liquid form.

- Proton pump inhibitors. These agents are indicated in patients who require complete acid suppression (eg, infants with chronic respiratory disease or neurologic disabilities); administer proton pump inhibitors with the first meal of the day; children with nasogastric or gastrostomy tubes may have granules mixed with an acidic juice or a suspension; tubes must then be flushed to prevent blockage.

Nursing Management

Nursing care for a child with gastroesophageal reflux includes the following:

Nursing Assessment

Assessment of the child includes:

- History. One must remember that the typical symptoms (eg, heartburn, vomiting, regurgitation) in adults cannot be readily assessed in infants and children; pediatric patients with gastroesophageal reflux typically cry and report sleep disturbance and decreased appetite.

- Physical exam. No classic physical signs of gastroesophageal reflux are recognized in the pediatric population (although an infant or toddler arriving in the office wearing a bib is often a sure tip off); one exception would be the relatively uncommon Sandifer syndrome, which is often misdiagnosed as spastic torticollis.

Nursing Diagnosis

Based on the assessment data, the major nursing diagnosis is:

- Imbalanced nutrition: less than body requirements related to the inability to intake enough food because of reflux.

- Acute pain related to irritated esophageal mucosa.

- Imbalanced nutrition: more than body requirements related to eating to try to assuage the pain.

- Risk for aspiration related to esophageal compromise affecting the lower esophageal sphincter.

- Deficient knowledge related to lack of information regarding condition/disease process.

- Anxiety related to change in the health status of the infant (possible surgical intervention).

- Risk for injury related to abnormal blood profile.

Nursing Care Planning and Goals

Main Article: 7 Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) Nursing Care Plans

The major nursing care planning goals for a child with gastroesophageal reflux:

- Patient will ingest daily nutritional requirements in accordance to his activity level and metabolic needs.

- Client will report pain is relieved.

- Client will achieve and maintain an adequate body weight.

- Client will maintain patent airway.

- Client will have increased knowledge of actions that reduce reflux.

- Client (caregivers) will report a decrease in their anxiety level to none or mild.

- Child will experience the absence of esophageal bleeding (negative Guaiac tests).

- Child will manifest appropriate growth.

Nursing Interventions

Nursing interventions for a child with gastroesophageal reflux are:

- Improve nutrition. Accurately measure the patient’s weight and height; encourage small frequent meals of high calories and high protein foods; instruct to remain in upright position at least 2 hours after meals; avoiding eating 3 hours before bedtime; instruct patient to eat slowly and masticate foods well; establish a dietary plan for weekly goals of weight loss of one pound; encourage patient to make gradual changes in dietary habits; provide activities for the patient that do not center around or are associated with meals or snacks.

- Relieve pain. Assess for heartburn, and carefully assess pain location and discern pain from GERD and angina pectoris.

- Prevent aspiration. Avoid placing the patient in supine position, have the patient sit upright after meals; instruct patient to avoid highly seasoned food, acidic juices, alcoholic drinks, bedtime snacks, and foods high in fat; elevate HOB while in bed.

- Enforce health education. Provide patient and folks with information regarding disease process, health practices that can be changed, and medications to be utilized; instruct patient and folks in medications, effects, side effects, and to report to physician if symptoms persist despite medical treatment.

- Relieve anxiety. Allow verbalization of concerns and to ask inquiries about illness, treatment, surgery, and recovery by parents; encourage parents to stay with the child

and to assist in care; communicate frequently with parents and provide easy-to-understand and truthful answers to questions; utilize pictures, drawings, and models for explanations. - Prevent injury. Inform parents that infant usually outgrows the disorder and attains normal function by 6 weeks of age and those with a persistent reflux problem usually resolve by 6 months of age; assist and prepare parents and infant for diagnostic examination and possible surgical procedure; educate and instruct to do Guaiac test on stool and vomitus and allow to return demonstration.

Evaluation

Goals are met as evidenced by:

- Patient will ingest daily nutritional requirements in accordance to his activity level and metabolic needs.

- Client will report pain is relieved.

- Client will achieve and maintain an adequate body weight.

- Client will maintain patent airway.

- Client will have increased knowledge of actions that reduce reflux.

- Client (caregivers) will report a decrease in their anxiety level to none or mild.

- Child will experience absence of esophageal bleeding (negative Guaiac tests).

- Child will manifest appropriate growth.

Documentation Guidelines

Documentation in a child with gastroesophageal reflux includes:

- Individual findings include factors affecting, interactions, the nature of social exchanges, and specifics of individual behavior.

- Intake and output.

- Cultural and religious beliefs, and expectations.

- Plan of care.

- Teaching plan.

- Responses to interventions, teaching, and actions performed.

- Attainment or progress toward the desired outcome.

Leave a Comment