Rheumatic fever is a systemic inflammatory condition that arises as a complication of untreated or inadequately managed streptococcal throat infections, particularly group A streptococcus. This immune-mediated disease primarily affects children and adolescents, causing inflammation in various parts of the body, including the heart, joints, skin, and central nervous system. Rheumatic fever can lead to severe cardiac complications, such as rheumatic heart disease, if left unaddressed.

What is Rheumatic Fever?

Rheumatic fever is an inflammatory disease that can develop as a complication of inadequately treated strep throat or scarlet fever.

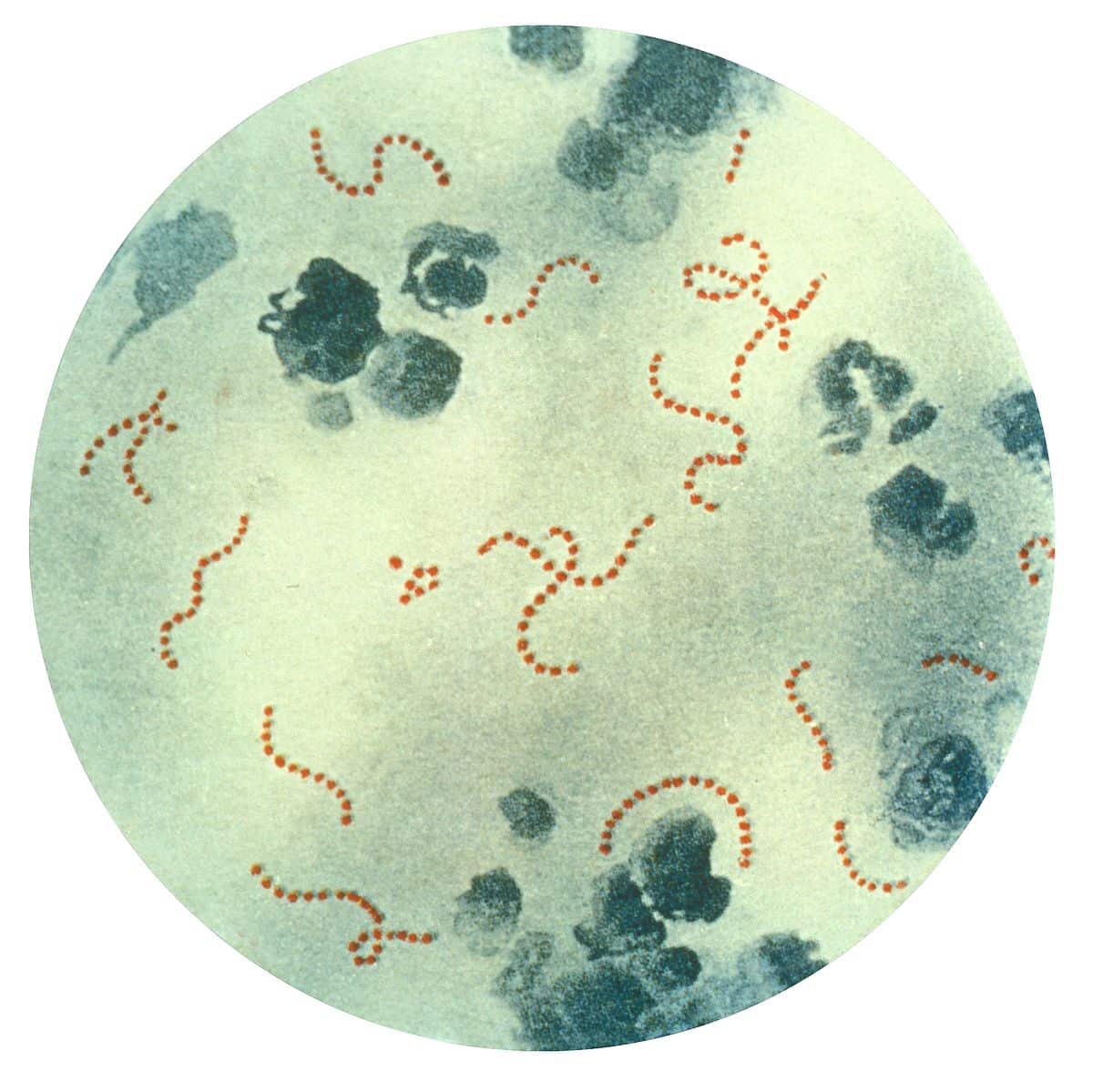

- Rheumatic fever (RF) is a systemic illness that may occur following group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal (GABHS) pharyngitis in children.

- Studies in the 1950s during an epidemic on a military base demonstrated 3% incidence of rheumatic fever in adults with streptococcal pharyngitis not treated with antibiotics.

- Strep throat and scarlet fever are caused by an infection with streptococcus bacteria.

Pathophysiology

Rheumatic fever develops in children and adolescents following pharyngitis with GABHS (ie, Streptococcus pyogenes).

- The organisms attach to the epithelial cells of the upper respiratory tract and produce a battery of enzymes, which allows them to damage and invade human tissues.

- After an incubation period of 2-4 days, the invading organisms elicit an acute inflammatory response, with 3-5 days of sore throat, fever, malaise, headache, and elevated leukocyte count.

- In a small percentage of patients, infection leads to rheumatic fever several weeks after a sore throat has resolved; only infections of the pharynx have been shown to initiate or reactivate rheumatic fever.

- Direct contact with oral (PO) or respiratory secretions transmits the organism, and crowding enhances transmission; patients remain infected for weeks after symptomatic resolution of pharyngitis and may serve as a reservoir for infecting others.

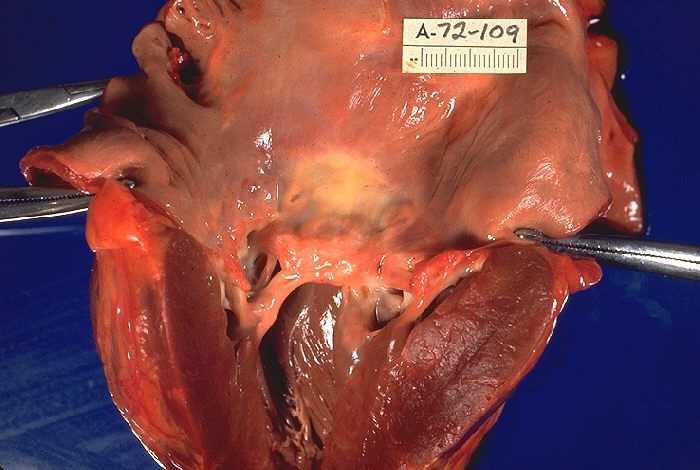

- Severe scarring of the valves develops during a period of months to years after an episode of acute rheumatic fever, and recurrent episodes may cause progressive damage to the valves.

- The mitral valve is affected most commonly and severely (65-70% of patients); the aortic valve is affected second most commonly (25%).

Statistics and Incidences

Rheumatic fever is most common in 5- to 15-year-old children, though it can develop in younger children and adults.

- The prevalence of RHD in the United States was less than 0.05 per 1000 population, with only rare regional outbreaks reported in Tennessee in the 1960s and in Utah, Ohio, and Pennsylvania in the 1980s.

- However, a recent assessment of temporal trends of patients diagnosed with acute rheumatic fever in the United States from 2001-2011 showed that since 2001, national acute rheumatic fever admissions have steadily increased, with a peak in 2005, and decreased thereafter.

- Worldwide, there are over 15 million cases of RHD, with 282,000 new cases and 33,000 deaths from this disease each year.

- RHD is the major cause of morbidity from rheumatic fever and is the major cause of mitral insufficiency and stenosis in the United States and the world.

- Native Hawaiians and Maori (both of Polynesian descent) have a higher incidence of rheumatic fever; the incidence of rheumatic fever in these patients is 13.4 per 100,000 hospitalized children per year, even with antibiotic prophylaxis of streptococcal pharyngitis.

- Rheumatic fever occurs in equal numbers in males and females; females with rheumatic fever fare worse than males and have a slightly higher incidence of chorea.

- Rheumatic fever is principally a disease of childhood, with a median age of 10 years; however, GABHS pharyngitis is uncommon in children younger than 3 years, and acute rheumatic fever is extremely rare in these younger children in industrialized countries.

Causes

Rheumatic fever is believed to result from an autoimmune response; however, the exact pathogenesis remains unclear.

- GABHS infection. Rheumatic fever only develops in children and adolescents following group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal (GABHS) pharyngitis and only infections of the pharynx initiate or reactivate rheumatic fever.

- Molecular mimicry. So-called molecular mimicry between streptococcal and human proteins is felt to involve both the B and T cells of peripheral blood, with infiltration of the heart by T cells; some believe that increased production of inflammatory cytokines is the final mechanism of the autoimmune reaction that causes damage to cardiac tissue in RHD.

- Streptococcal antigens. Streptococcal antigens, which are structurally similar to those in the heart, include hyaluronate in the bacterial capsule, cell wall polysaccharides (similar to glycoproteins in heart valves), and membrane antigens that share epitopes with the sarcolemma and smooth muscle.

- Decrease in regulatory T-cells. Decreased levels of regulatory T-cells have also been associated with rheumatic heart disease and with increased severity.

Clinical Manifestations

Revised in 1992 and again in 2016, the modified Jones criteria provide guidelines for making the diagnosis of rheumatic fever; the modified Jones criteria for recurrent rheumatic fever require the presence of 2 major, or 1 major and 2 minor, or 3 minor criteria for the diagnosis of rheumatic fever.

Major Diagnostic Criteria

- Carditis. Carditis in the child may be clinical and/or subclinical (echo).

- Polyarthritis. Monoarthritis or polyarthralgia are adequate to achieve major diagnostic criteria in Moderate/High-risk populations; for polyarthralgia exclusion of other more likely causes is also required.

- Chorea. Jerky, uncontrollable body movements (Sydenham chorea, or St. Vitus’ dance) — most often in the hands, feet, and face.

- Subcutaneous nodules. Small, painless bumps (nodules) beneath the skin.

- Erythema marginatum. Flat or slightly raised, painless rash with a ragged edge.

Minor Diagnostic Criteria

- Fever. Fever of ≥38.5°C ( ≥38°C to achieve a minor diagnostic criteria in Moderate/High-risk populations.

- Polyarthralgia. Painful and tender joints — most often in the knees, ankles, elbows, and wrists.

- Prolonged PR interval. Prolonged PR interval for age on electrocardiography.

- Increased ESR. Elevated peak erythrocyte sedimentation rate during acute illness ≥60 mm/h and/or C-reactive protein ≥3.0 mg/dl.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

Although there’s no single test for rheumatic fever, diagnosis is based on medical history, physical exam, and certain test results.

- Throat culture. Throat cultures for GABHS infections usually are negative by the time symptoms of rheumatic fever or rheumatic heart disease (RHD) appear; make attempts to isolate the organism prior to the initiation of antibiotic therapy to help confirm a diagnosis of streptococcal pharyngitis and to allow typing of the organism if it is isolated successfully.

- Rapid antigen detection test. This test allows rapid detection of group A streptococci (GAS) antigen, allowing the diagnosis of streptococcal pharyngitis to be made and antibiotic therapy to be initiated while the patient is still in the physician’s office.

- Antistreptococcal antibodies. Clinical features of rheumatic fever begin when antistreptococcal antibody levels are at their peak; thus, these tests are useful for confirming previous GAS infection; antistreptococcal antibodies are particularly useful in patients who present with chorea as the only diagnostic criterion.

- Acute-phase reactants. C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rates are elevated in individuals with rheumatic fever due to the inflammatory nature of the disease; both tests have high sensitivity but low specificity for rheumatic fever.

- Heart reactive antibodies. Tropomyosin is elevated in persons with acute rheumatic fever.

- Rapid detection test for D8/17. This immunofluorescence technique for identifying the B-cell marker D8/17 is positive in 90% of patients with rheumatic fever and may be useful for identifying patients who are at risk of developing rheumatic fever.

- Chest radiography. Cardiomegaly, pulmonary congestion, and other findings consistent with heart failure may be observed on chest radiographs in individuals with rheumatic fever.

- Echocardiography. In individuals with acute RHD, echocardiography identified and quantitated valve insufficiency and ventricular dysfunction.

Medical Management

Therapy is directed towards eliminating GABHS pharyngitis (if still present), suppressing inflammation from the autoimmune response, and providing supportive treatment of congestive heart failure (CHF).

- Anti-inflammatory. Treatment of the acute inflammatory manifestations of acute rheumatic fever consists of salicylates and steroids; aspirin in anti-inflammatory doses effectively reduces all manifestations of the disease except chorea, and the response typically is dramatic.

- Corticosteroids. If moderate to severe carditis is present as indicated by cardiomegaly, third-degree heart block, or CHF, add PO prednisone to salicylate therapy.

- Anticonvulsant medications. For severe involuntary movements caused by Sydenham chorea, your doctor might prescribe an anticonvulsant, such as valproic acid (Depakene) or carbamazepine (Carbatrol, Tegretol, others).

- Antibiotics. Your child’s doctor will prescribe penicillin or another antibiotic to eliminate the remaining strep bacteria.

- Surgical care. When heart failure persists or worsens after aggressive medical therapy for acute RHD, surgery to decrease valve insufficiency may be lifesaving; approximately 40% of patients with acute rheumatic fever subsequently develop mitral stenosis as adults.

- Diet. Advise a nutritious diet without restrictions except in patients with CHF, who should follow a fluid-restricted and sodium-restricted diet; potassium supplementation may be necessary because of the mineralocorticoid effect of corticosteroids and diuretics if used.

- Activity. Initially, place patients on bed rest, followed by a period of indoor activity before they are permitted to return to school; do not allow full activity until the APRs have returned to normal; patients with chorea may require a wheelchair and should be on homebound instruction until the abnormal movements resolve.

Pharmacologic Management

Treatment and prevention of group A streptococci pharyngitis outlined here are based on the current recommendations of the American Heart Association Practice Guidelines on Prevention of Rheumatic Fever and Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute Streptococcal Pharyngitis.

- Antibiotics. The roles of antibiotics are to (1) initially treat GABHS pharyngitis, (2) prevent recurrent streptococcal pharyngitis, rheumatic fever (RF), and rheumatic heart disease (RHD), and (3) provide prophylaxis against bacterial endocarditis.

- Anti-inflammatory agents. Manifestations of acute rheumatic fever (including carditis) typically respond rapidly to therapy with anti-inflammatory agents; aspirin, in anti-inflammatory doses, is DOC; prednisone is added when evidence of worsening carditis and heart failure is noted.

- Therapy for congestive heart failure. Heart failure in RHD probably is related in part to the severe insufficiency of the mitral and aortic valves and in part to pancarditis; therapy traditionally has consisted of an inotropic agent (digitalis) in combination with diuretics (furosemide, spironolactone) and afterload reduction (captopril).

Nursing Management

Nursing care for a child with rheumatic fever includes:

Nursing Assessment

Nursing assessments for a child with rheumatic fever are as follows:

- History. Obtain a complete up-to-date history from the child and the caregiver; ask about a recent sore throat or upper respiratory infection; find out when the symptoms began, the extent of the illness, and what if any treatment was obtained.

- Physical exam. Begin with a careful review of all systems, and note the child’s physical condition; observe for any signs that may be classified as major or minor manifestations; in the physical exam, observe for elevated temperature and pulse, and carefully examine for erythema marginatum, subcutaneous nodules, swollen or painful joints, or signs of chorea.

Nursing Diagnoses

Based on the assessment data, the major nursing diagnoses are:

- Acute pain related to joint pain when extremities are touched or moved.

- Deficient diversional activity related to prescribed bed rest.

- Activity intolerance related to carditis or arthralgia.

- Risk for injury related to chorea.

- Risk for noncompliance with prophylactic drug therapy related to financial or emotional burden of lifelong therapy.

- Deficient knowledge of caregiver related to the condition, need for long-term therapy, and risk factors.

Nursing Care Planning and Goals

Main Article 4 Acute Rheumatic Fever Nursing Care Plans

The major nursing care planning goals for rheumatic fever are:

- Reducing pain.

- Providing diversional activities and sensory stimulation.

- Conserving energy.

- Preventing injury.

Nursing Interventions

Nursing interventions for a child with rheumatic fever include:

- Provide comfort and reduce pain. Position the child to reduce joint pain; warm baths and gentle range-of-motion exercises help to alleviate some of the joint discomforts; use pain indicator scales with children so they are able to express the level of their pain.

- Provide diversional activities and sensory stimulation. For those who do not feel very ill, bed rest can cause distress or resentment; be creative in finding diversional activities that allow bed rest but prevent restlessness and boredom, such as a good book; quiet games can provide some entertainment, and plan all activities with the child’s developmental stage in mind.

- Promote energy conservation. Provide rest periods between activities to help pace the child’s energies and provide for maximum comfort; if the child has chorea, inform visitors that the child cannot control these movements, which are as upsetting to the child as they are to others.

- Prevent injury. Protect the child from injury by keeping the side rails up and padding them; do not leave a child with chorea unattended in a wheelchair, and use all appropriate safety measures.

Evaluation

Goals are met as evidenced by:

- Reducing pain.

- Providing diversional activities and sensory stimulation.

- Conserving energy.

- Preventing injury.

Documentation Guidelines

Documentation in a child with rheumatic fever includes:

- Baseline and subsequent assessment findings to include signs and symptoms.

- Individual cultural or religious restrictions and personal preferences.

- Plan of care and persons involved.

- Teaching plan.

- Client’s responses to teachings, interventions, and actions performed.

- Attainment or progress toward the desired outcome.

- Long-term needs, and who is responsible for actions to be taken.

Leave a Comment