Tracheoesophageal atresia (TEA) is a congenital anomaly involving the abnormal development of the trachea and esophagus during fetal development. As nursing professionals, understanding the intricacies of TEA and providing early detection and holistic care is essential in supporting infants and their families facing the challenges of this complex condition.

This article aims to serve as a comprehensive nursing guide to tracheoesophageal atresia, delving into its etiology, clinical manifestations, diagnostic methods, surgical interventions, and long-term management.

What is Tracheoesophageal Atresia?

Tracheoesophageal atresia was first described anecdotally in the 17th century.

- Esophageal atresia refers to a congenitally interrupted esophagus.

- One or more fistulae may be present between the malformed esophagus and the trachea.

- In 1670, Durston described the first case of esophageal atresia in one conjoined twin; in 1696, Gibson provided the first description of esophageal atresia with a distal TEF.

- In 1862, Hirschsprung (a famous pediatrician from Copenhagen) described 14 cases of esophageal atresia. In 1898, Hoffman attempted primary repair of the defect but was not successful and resorted to the placement of a gastrostomy.

Pathophysiology

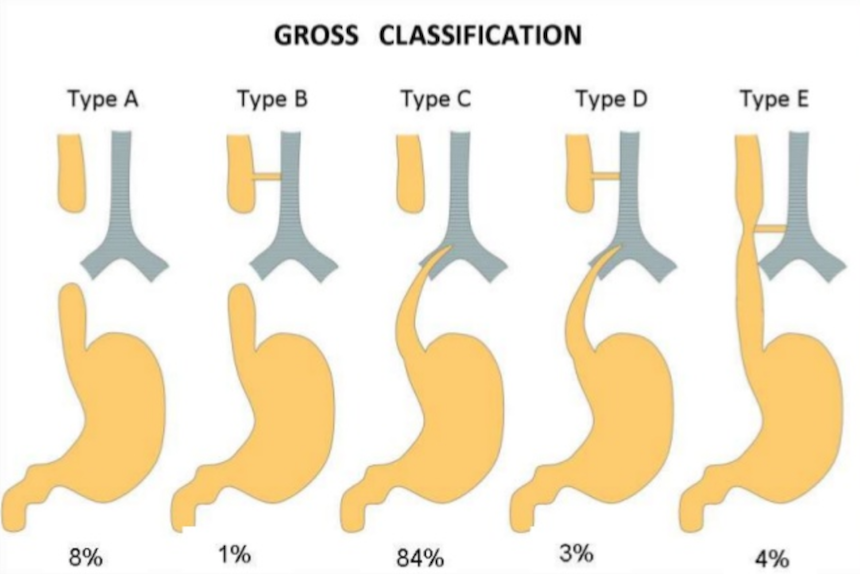

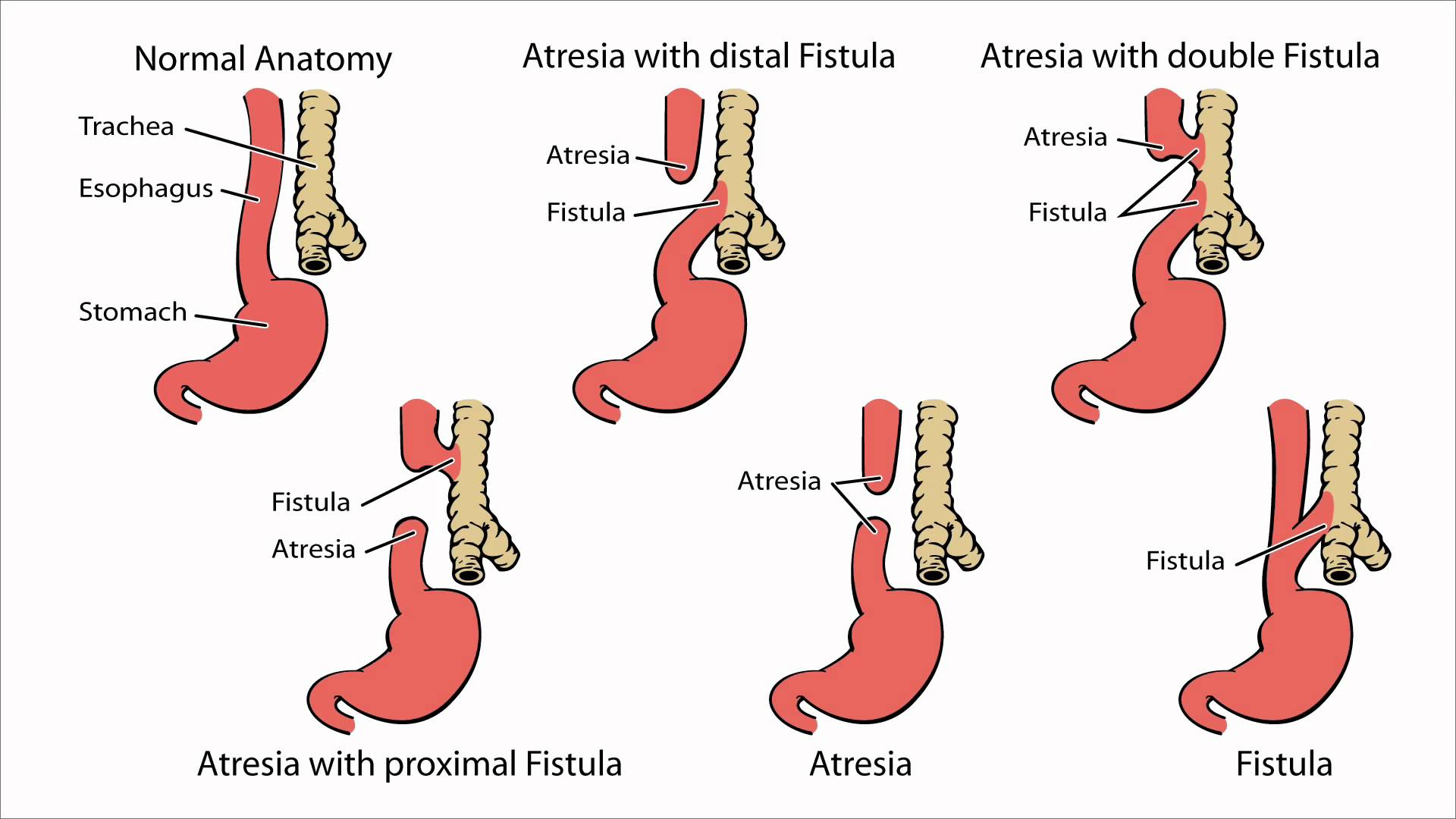

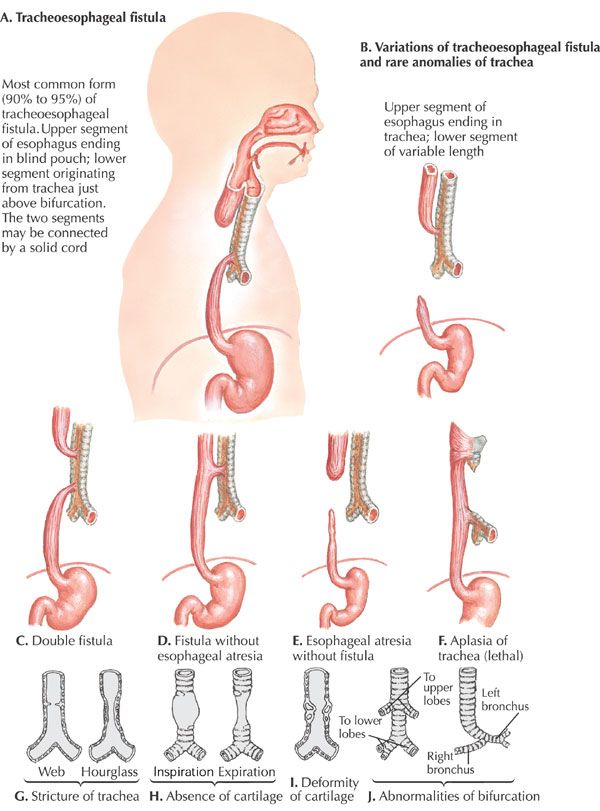

The variants of tracheoesophageal atresia have been described using many anatomic classification systems.

- To avoid ambiguity, the clinician should use a narrative description; nevertheless, Gross of Boston described the classification system that is most often cited.

- According to the system formulated by Gross, the types of esophageal atresia and their approximate incidence in all infants born with esophageal anomalies are as follows:

- Type A – Esophageal atresia without fistula or so-called pure esophageal atresia (10%)

Type B – Esophageal atresia with proximal TEF (<1%)

Type C – Esophageal atresia with distal TEF (85%)

Type D – Esophageal atresia with proximal and distal TEFs (<1%)

Type E – TEF without esophageal atresia or so-called H-type fistula (4%)

Type F – Congenital esophageal stenosis (<1%) (not discussed in this article) - A fetus with esophageal atresia cannot effectively swallow amniotic fluid, especially when TEF is absent; in a fetus with esophageal atresia and a distal TEF, some amniotic fluid presumably flows through the trachea and down the fistula to the gut.

- The neonate with esophageal atresia cannot swallow and drools copious amounts of saliva.

- Also, air from the trachea can pass down the distal fistula when the baby cries, strains, or receives ventilation; this condition can lead to an acute gastric perforation, which is often lethal.

- Prerepair esophageal manometric studies have revealed that the distal esophagus in esophageal atresia is essentially dysmotile, with poor or absent propagating peristaltic waves.

Causes

No human teratogens that cause esophageal atresia are known.

- Genetics. Esophageal atresia that occurs in families has been reported; a 2% risk of recurrence is present when a sibling is affected; the occasional association of esophageal atresia with trisomies 21, 13, and 18 further suggests genetic causation.

- O’Rahilly theory. In 1984, O’Rahilly proposed that a fixed cephalad point of tracheoesophageal separation is present, with the tracheobronchial and esophageal elements elongating in a caudal direction from this point; this theory does not easily account for esophageal atresia but explains TEF as a deficiency or breakdown of esophageal mucosa, which occurs as the linear growth of the organ exceeds the cellular division of the esophageal epithelium.

- Kluth’s theory. In a 1987 report, Kluth eschewed the concept that tracheoesophageal septation has a key role in the development of esophageal atresia; instead, he based the embryopathologic process on the faulty development of the early, but already differentiated, trachea and esophagus, in which a dorsal fold comes to lie too far ventrally; thus, the early tracheoesophagus remains undivided.

- Spilde et al theory. In 2003, Spilde et al reported esophageal atresia-TEF formations in the embryos of rat models of doxorubicin-induced teratogenesis; specific absences of certain fibroblast growth factor (FGF) elements have been reported, specifically FGF1 and the IIIb splice variant of the FGF2R receptor; these specific FGF-signaling absences are postulated to allow the nonbranching development of the fistulous tract from the foregut, which then establishes continuity with the developing stomach.

- Orford’s theory. In 2001, Orford et al postulated that the ectopic, ventrally displaced location of the notochord in an embryo at 21 days’ gestation can lead to a disruption of the gene locus, sonic hedgehog-signaled apoptosis in the developing foregut, and variants of esophageal atresia; this situation may be due to various early gestation teratogenic influences such as twinning, toxin exposure, or possible abortion.

Statistics and Incidences

Incidence of tracheoesophageal atresia are as follows:

- The incidence of esophageal atresia is 1 case in 3000-4500 births.

- Internationally, the highest incidence of this disorder is reported in Finland, where it is 1 case in 2500 births.

Clinical Manifestations

The signs and symptoms of tracheoesophageal atresia are:

- Excessive oral secretions. Characteristically, the neonate born with esophageal atresia drools and has substantial mucus, with excessive oral secretions.

- Choking upon feeding. If suckling at the breast or bottle is allowed, the baby appears to choke and may have difficulty maintaining an airway; significant respiratory distress may result.

- Seal-bark cough. In the delivery room, the affected infant may have the sonorous seal-bark cough that indicates concomitant tracheomalacia.

- Oral obstruction. If an oral tube is placed to suction the stomach, as it is in some delivery rooms, it characteristically becomes blocked 10-11 cm from the lips.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

Assessing and diagnosing a patient with tracheoesophageal atresia include:

- Laboratory studies. In babies with esophageal atresia, samples should be obtained to determine baseline values for complete blood count (CBC); electrolyte levels; venous gas concentrations; blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and serum creatinine levels; blood glucose level; and serum calcium level.

- Ultrasonography. Prenatal ultrasonography may reveal the size of the gastric bubble, polyhydramnios, and VACTERL (vertebral defects, anorectal malformations, cardiovascular defects, tracheoesophageal defects, renal anomalies, and limb deformities) anomalies, all of which may indicate esophageal atresia in the fetus.

- Echocardiography. Echocardiography is indicated early in the care of infants with esophageal atresia who have clinical signs of cardiovascular disease.

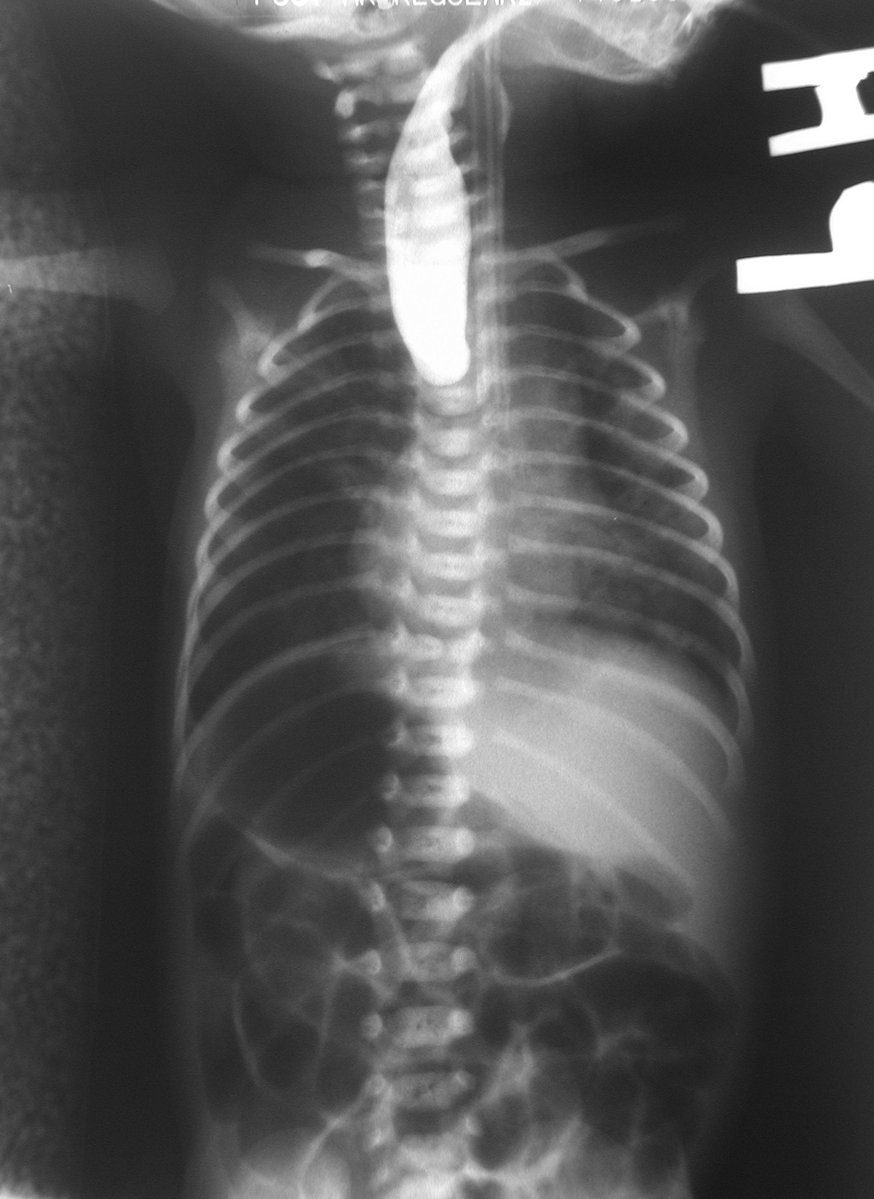

- Chest radiography. Chest radiography is mandatory and should be performed as soon as possible if esophageal atresia is suspected.

Medical Management

The treatment plan for each baby must be individualized.

- Tube placement. Management plans for a delayed repair of the esophageal atresia may include placing a 10-French Replogle double-lumen tube through the mouth or nose well into the upper pouch to provide continuous suction of pooled secretions from the proximal portion of the atretic esophagus; the baby may be positioned in the 45° sitting position; prophylactic broad-spectrum antibiotics (eg, ampicillin and gentamicin) may be used.

- Gastrostomy. If no distal TEF is present, a gastrostomy may be created. In such cases, the stomach is small, and laparotomy is required; when a baby is ventilated with high pressures, the gastrostomy may offer a route of decreased resistance, causing the ventilation gases to flow through the distal fistula and out the gastrostomy site.

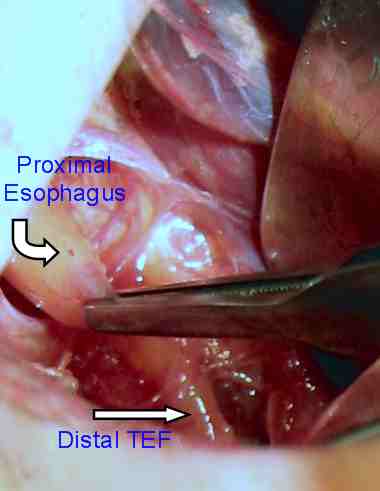

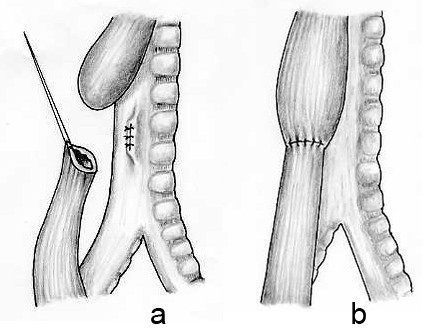

- TEF ligation. In cases such as those above or in cases in which a distal fistula continues to cause lung soiling, distal TEF ligation should be considered; this ligation is performed by means of a right-side thoracotomy, ideally via an extrapleural approach.

- Flourish Pediatric Esophageal Atresia Anastomosis. In May 2017, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the Flourish Pediatric Esophageal Atresia Anastomosis (Cook Medical) for management of esophageal atresia in infants up to 1-year-old who do not have teeth and do not have a TEF (or have had a TEF repaired); the device closes the gap in the esophagus by using magnets to pull together the upper and lower portions of the esophagus; it is not indicated for use in patients in whom the distance between the esophageal segments is 4 cm or greater.

- Repair of esophageal atresia. In some pediatric surgical centers, surgeons are gaining experience in repairing esophageal atresia by means of a minimally invasive thoracoscopic approach; this approach should be undertaken only by those who have extensive experience in pediatric thoracoscopic surgery.

- Chest tube care. The chest draining tube is placed in 2 cm of water only to seal it; it is not connected to a suction device, which could encourage an anastomotic leak.

Nursing Management

Nursing care of an infant with tracheoesophageal atresia include:

Nursing Assessment

Assessment of an infant with tracheoesophageal atresia include:

- History. A mother who is carrying a fetus with esophageal atresia may have polyhydramnios, which occurs in approximately 33% of mothers with fetuses with esophageal atresia and distal tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF) and in virtually 100% of mothers with fetuses with esophageal atresia without fistula.

- Physical exam. The acronym VACTERL (vertebral defects, anorectal malformations, cardiovascular defects, tracheoesophageal defects, renal anomalies, and limb deformities) refers a set of associated anomalies that should be readily apparent upon physical examination; if any of these anomalies are present, the presence of the others must be assessed; the VACTERL syndrome exists when three or more of the associated anomalies are present; this syndrome occurs in approximately 25% of all patients with esophageal atresia.

Nursing Diagnosis

Based on the assessment data, the major nursing diagnoses are:

- Impaired gaseous exchange related to abnormal opening between esophagus and trachea as evidenced by cyanosis.

- Impaired swallowing related to mechanical obstruction.

- Risk for injury related to surgical procedure.

- Anxiety related to difficulty swallowing, discomfort due to surgery.

- Altered family processes related to children with physical defects.

- Risk for aspiration related to difficulty in swallowing.

Nursing Care Planning and Goals

The major nursing care planning goals for patients with Tracheoesophageal atresia are:

- Patient is free of signs of aspiration and the risk of aspiration is decreased.

- Patient swallows and digests oral, nasogastric, or gastric feeding without aspiration.

- Patient displays ability to safety swallow, as evidenced by absence of aspiration, no evidence of coughing or choking during eating/drinking, no stasis of food in oral cavity after eating, ability to ingest foods/fluids.

- Patient remains free of injuries.

- Family caregivers describe own anxiety and coping patterns.

- Family caregivers identify strategies to reduce anxiety.

Nursing Interventions

Nursing interventions for a child with tracheoesophageal atresia are:

- Ensure safe swallowing. Place suction equipment at the bedside, and suction as needed; ensure proper nutrition by consulting with physician for enteral feedings, preferably a PEG tube in most cases.

- Prevent aspiration. Check placement before feeding, using tube markings, x-ray study (most accurate), pH of gastric fluid, and color of aspirate as guides; if ordered by physician, put several drops of blue or green food coloring in tube feeding to help indicate aspiration. In addition, test the glucose in tracheobronchial secretions to detect aspiration of enteral feedings; elevate the head of bed to 30 to 45 degrees while feeding the patient and for 30 to 45 minutes afterward if feeding is intermittent; and instruct in signs and symptoms of aspiration.

- Reduce anxiety. Allow family caregivers to talk about anxious feelings and examine anxiety-provoking situations if they are identifiable; assist them in developing new anxiety-reducing skills (e.g., relaxation, deep breathing, positive visualization, and reassuring self-statements); explain all activities, procedures, and issues that involve the patient; use nonmedical terms and calm, slow speech; do this in advance of procedures when possible, and validate patient’s understanding.

Evaluation

Goals are met as evidenced by:

- Patient is free of signs of aspiration and the risk of aspiration is decreased.

- Patient swallowed and digests oral, nasogastric, or gastric feeding without aspiration.

- Patient displayed ability to safety swallow, as evidenced by absence of aspiration, no evidence of coughing or choking during eating/drinking, no stasis of food in oral cavity after eating, ability to ingest foods/fluids.

- Patient remained free of injuries.

- Family caregivers described own anxiety and coping patterns.

- Family caregivers identified strategies to reduce anxiety.

Documentation Guidelines

Documentation in an infant with tracheoesophageal atresia include:

- Individual findings, including factors affecting, interactions, nature of social exchanges, specifics of individual behavior.

- Intake and output.

- Signs of infection.

- Cultural and religious beliefs, and expectations.

- Plan of care.

- Teaching plan.

- Responses to interventions, teaching, and actions performed.

- Attainment or progress toward the desired outcome.

Leave a Comment