Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis (JRA), also known as Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA), is a chronic autoimmune disorder that affects children and adolescents, making it a significant concern for nurses. This condition involves inflammation of the joints, leading to pain, swelling, and stiffness, which can impair a child’s mobility and overall quality of life. JRA is the most common chronic arthritis in children and is characterized by various subtypes, each presenting unique challenges in diagnosis and management.

Table of Contents

- What is Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis?

- Pathophysiology

- Statistics and Incidences

- Causes

- Clinical Manifestations

- Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

- Medical Management

- Nursing Management

What is Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis?

- Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA), also known as Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA), is the most common chronic rheumatologic disease in children and is one of the most common chronic diseases of childhood.

- It represents a group of disorders that share the clinical manifestation of chronic joint inflammation.

- Connective tissues are those that provide a supportive framework and protective covering for the body, such as the musculoskeletal system and skin and mucous membranes.

Pathophysiology

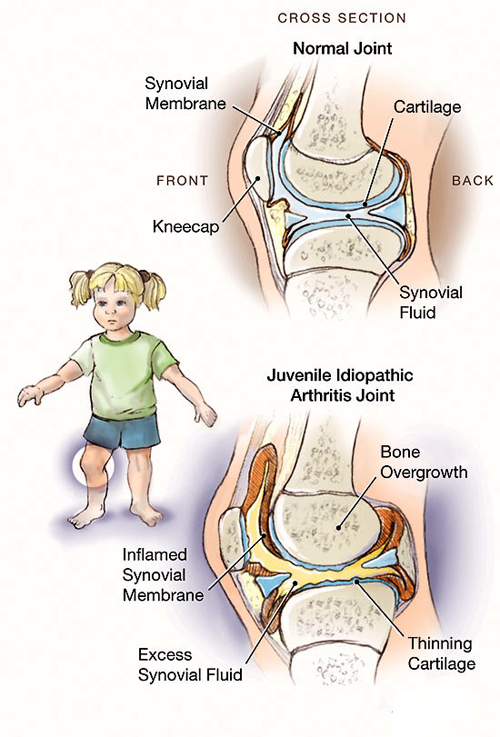

Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis is a genetically complex disorder in which multiple genes are important for disease onset and manifestations.

- Humoral and cell-mediated immunity are involved in the pathogenesis of JRA.

- T lymphocytes have a central role, releasing proinflammatory cytokines (eg, tumor necrosis factor–alpha [TNF-α], interleukin [IL]-6, IL-1) and favoring a type-1 helper T-lymphocyte response.

- Studies of T-cell receptor expression confirm recruitment of T-lymphocytes specific for synovial nonself antigens.

- Evidence for abnormalities in the humoral immune system include the increased presence of autoantibodies (especially antinuclear antibodies), increased serum immunoglobulins, the presence of circulating immune complexes, and complement activation.

- Chronic inflammation of synovium is characterized by B-lymphocyte infiltration and expansion.

- Macrophages and T-cell invasion are associated with the release of cytokines, which evoke synoviocyte proliferation.

- Some pediatric rheumatologists view systemic-onset JRA as an autoinflammatory disorder, such as familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) or cryopyrin-associated periodic fever syndromes, rather than a subtype of JRA.

- This theory is supported by work demonstrating similar expression patterns of a phagocytic protein (S100A12) in systemic-onset JRA and FMF, as well as the same marked responsiveness to IL-1 receptor antagonists.

Statistics and Incidences

The occurrence of Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis appears to peak at two age levels: 1 to 3 years and 8 to 12 years.

- Approximately 300,000 children in the United States are estimated to have some type of arthritis.

- For JRA, the prevalence has ranged from 1.6 to 86.1 cases per 100,000.

- Worldwide, JRA appears to occur more frequently in certain populations (eg, indigenous peoples) from such disparate areas as British Columbia and Norway.

- Disease-associated mortality for JRA is difficult to quantify, but it is estimated to be less than 1% in Europe and less than 0.5% in North America.

- Most deaths associated with JRA in Europe are related to amyloidosis, and most in the United States are related to infections.

- Girls with an oligoarticular onset outnumber boys by a ratio of 3:1. In children with uveitis, the ratio of girls to boys is 5-6.6:1, and in children with polyarticular onset, girls outnumber boys by 2.8:1.

Causes

The etiology of Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis is unknown, and the genetic component is complex, making clear distinctions between the various subtypes difficult.

Clinical Manifestations

Physical findings are important to provide criteria for diagnosis and to detect abnormalities suggestive of alternative etiologies.

- Arthritis. Arthritis is defined as either intra-articular swelling on examination or as limitation of joint motion in association with pain, warmth, or erythema of the joint.

- Loss of motion. The hips, temporomandibular joint, and small joints in the spine do not demonstrate swelling when affected by synovitis but demonstrate the combination of loss of motion and pain.

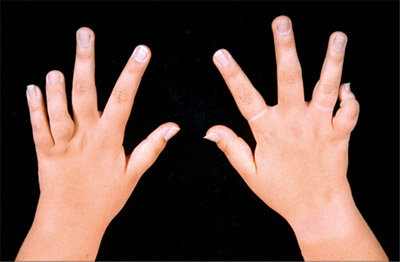

- Synovitis. In synovitis, the fingers may appear swollen, and the range of motion becomes painful.

- Swelling. A soft, boggy swelling is appreciated in the popliteal fossa.

- Joint inflammation. Joint inflammation occurs first; if untreated, inflammation leads to irreversible changes in joint cartilage, ligaments, and menisci.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

The diagnosis of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA) is based on the history and physical examination findings.

- Inflammatory markers. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) or C-reactive protein (CRP) level is usually elevated in children with systemic-onset JRA (with a disproportionate increase in the CRP) and may be elevated in those with polyarticular disease; however, it is often within the reference range in those with oligoarticular disease; other markers of inflammation include thrombocytosis, leukocytosis, complement, and, in a reverse fashion, albumin and hemoglobin.

- Complete blood count and metabolic panel. A complete blood count, liver function tests (to exclude the possibility of viral or autoimmune hepatitis), and assessment of renal function with serum creatinine levels should be done before starting treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), methotrexate (MTX), or tumor necrosis factor–alpha inhibitors.

- Antinuclear antibody test. A positive ANA is a marker for increased risk of anterior uveitis; children younger than 6 years at arthritis onset with a positive ANA finding are in the highest risk category for development of uveitis and need slit lamp screening every 3-4 months.

- Radiography. When only a single joint is affected, radiography is important to exclude other diseases, such as osteomyelitis.

- Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. CT scanning is the best method for analyzing bony abnormalities, but it has been largely superseded by MRI in the overall assessment of JRA; and MRI provides the most sensitive radiologic indicator of disease activity.

- Ultrasonography. On ultrasonograms, inflamed synovium can appear as an area of mixed echogenicity lining the articular cartilage; the vascularity of the synovium can be assessed with Doppler flow studies.

Medical Management

The ultimate goals in managing rheumatoid arthritis are to prevent or control joint damage, to prevent loss of function, and to decrease pain.

- Exercise. Exercise preserves joint range of motion and muscular strength, and it protects joint integrity by providing better shock absorption; types of exercises that may be advised include a muscle-strengthening program, range-of-motion activity, stretching of deformities, and endurance and recreational exercises.

- Synovectomy. Synovectomy is rarely needed, and long-term outcome is poor; however, it may be used in children in whom a single joint or just a few joints are involved and who have very active, proliferative synovitis.

- Osteotomy and arthrodesis. Osteotomy and arthrodesis are salvage procedures for patients whose JIA is associated with severe joint destruction or deformity.

- Total hip and knee replacements. Total hip and knee replacements provide excellent relief of pain and restore function in a functionally disabled child with debilitating disease.

Pharmacologic Management

Treatment is aimed at inducing remission with the least toxicity from medications with hopes of inducing a permanent remission.

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) interfere with prostaglandin synthesis through inhibition of the enzyme cyclooxygenase (COX), thus reducing swelling and pain; NSAIDs are used to treat all subtypes of JIA; they may help with pain and decrease swelling.

- Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) can retard or prevent disease progression and, thus, joint destruction and subsequent loss of function.

- Corticosteroids. Corticosteroids are potent anti-inflammatory drugs used in patients with JIA to bridge the time until DMARDs are effective.

- Immunomodulators. The recognition of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) and interleukin (IL)–1 as central proinflammatory cytokines has led to the development of agents that block these cytokines or their effects.

Nursing Management

The treatment and nursing management goal for juvenile rheumatoid arthritis is to maintain mobility and preserve joint function.

Nursing Assessment

The most important steps in diagnosing JRA are the medical history and physical exam.

- Medical history. Assess for the duration of symptoms, onset, affected joints, pain description, changes in physical activity, general health, history of arthritis, previous illness, and other symptoms associated with JRA.

- Physical exam. Assess the vital signs, auscultate the heart and lungs, palpate the abdomen, and examine the skin.

Nursing Diagnosis

Based on the assessment data, the major nursing diagnoses are:

- Acute pain related to tissue distension by fluid accumulation / inflammation, joint destruction.

- Impaired physical mobility related to skeletal deformities, pain, discomfort,activity intolerance, decreased muscle strength.

- Disturbed body image related to changes in ability to perform usual tasks.

- Self-care deficit related to musculoskeletal impairment.

- Deficient knowledge related to lack of exposure/recall.

Nursing Care Planning and Goals

Main Article 4 Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis Nursing Care Plans

The nurse should focus on the following nursing care planning goals for the child with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis:

- Report pain is relieved/controlled.

- Appear relaxed, able to sleep/rest and participate in activities appropriately.

- Follow prescribed pharmacological regimen.

- Incorporate relaxation skills and diversional activities into pain control program.

- Maintain position of function with absence/limitation of contractures.

- Maintain or increase strength and function of affected and/or compensatory body part.

- Demonstrate techniques/behaviors that enable resumption/continuation of activities.

- Verbalize increased confidence in ability to deal with illness, changes in lifestyle, and possible limitations.

- Verbalize understanding of condition/prognosis, and potential complications.Formulate realistic goals/plans for future.

Nursing Interventions

The nursing intervention appropriate for a child with JRA are:

- Physical therapy. Physical therapy includes exercise, application of splints, and heat.

- Activity. Stress to the caregivers the importance of encouraging the child to perform activities of daily living to maintain function and independence.

- Pain relief. Recommend or provide firm mattress or bedboard, small pillow; elevate linens with bed cradle as needed; and suggest patient assume position of comfort while in bed or sitting in chair.

- ROM exercises. Assist with active and passive ROM and resistive exercises and isometrics when able.

- Emotional support. Encourage verbalization about concerns of disease process, future expectations; give positive reinforcement for accomplishments; and acknowledge and accept feelings of grief, hostility, dependency.

- Health education. Review disease process, prognosis, and future expectations; discuss patient’s role in management of disease process through nutrition, medication, and balanced program of exercise and rest; and assist in planning a realistic and integrated schedule of activity, rest, personal care, drug administration, physical therapy, and stress management.

Evaluation

Goals are met as evidenced by:

- Reported pain is relieved/controlled.

- Appeared relaxed, able to sleep/rest and participate in activities appropriately.

- Followed prescribed pharmacological regimen.

- Incorporated relaxation skills and diversional activities into pain control program.

- Maintained position of function with absence/limitation of contractures.

- Maintained strength and function of affected and/or compensatory body part.

- Demonstrated techniques/behaviors that enable resumption/continuation of activities.

- Verbalized increased confidence in ability to deal with illness, changes in lifestyle, and possible limitations.

- Verbalized understanding of condition/prognosis, and potential complications.Formulate realistic goals/plans for future.

Documentation Guidelines

Documentation in a child with JRA include:

- Temperature and other assessment findings, including vital signs.

- Causative and contributing factors.

- Impact of condition on personal image and lifestyle.

- Current or recent antibiotic therapy.

- Plan of care.

- Teaching plan.

- Responses to interventions, teaching, and actions performed.

- Attainment or progress towards desired outcomes.

- Modifications to plan of care.

Can JAR be stopped from developing?