Reye syndrome is a rare but potentially life-threatening condition that primarily affects children and young adults recovering from viral infections, particularly influenza or chickenpox, and is characterized by acute brain and liver inflammation.

Reye syndrome can lead to rapid and severe neurological deterioration, making prompt recognition, close monitoring, and supportive care crucial in preventing complications.

What is Reye’s Syndrome?

The syndrome was first described in 1963 in Australia by RDK Reye and described a few months later in the United States by GM Johnson.

- Reye’s syndrome is characterized by acute noninflammatory encephalopathy and fatty degenerative liver failure.

- A dramatic decrease in the use of aspirin among children, in combination with the identification of medication reactions, toxins, and inborn errors of metabolism (IEMs) that present with Reye’s syndrome–like manifestations, have made the diagnosis of Reye’s syndrome exceedingly rare.

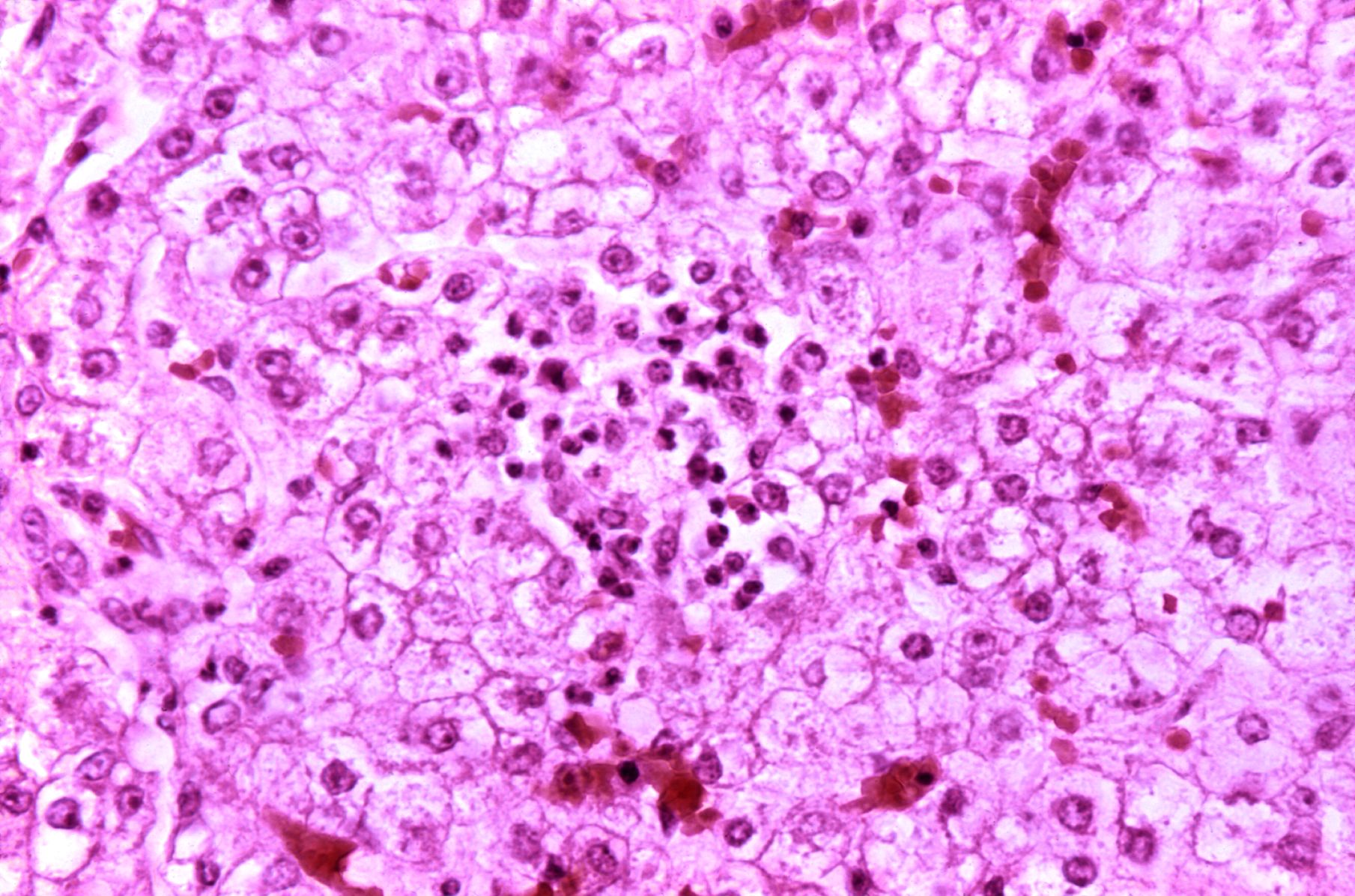

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of Reye’s syndrome appears as follows:

- The pathogenesis of Reye’s syndrome, while not precisely elucidated, appears to involve mitochondrial injury resulting in dysfunction that inhibits oxidative phosphorylation and fatty-acid beta-oxidation in a virus-infected, sensitized host.

- The host has usually been exposed to mitochondrial toxins, most commonly salicylates.

- Histologic changes include cytoplasmic fatty vacuolization in hepatocytes, astrocyte edema and loss of neurons in the brain, and edema and fatty degeneration of the proximal lobules in the kidneys.

- All cells have pleomorphic, swollen mitochondria that are reduced in number, along with glycogen depletion and minimal tissue inflammation.

- Hepatic mitochondrial dysfunction results in hyperammonemia, which is thought to induce astrocyte edema, resulting in cerebral edema and increased intracranial pressure (ICP).

Statistics and Incidences

In the United States, national surveillance for Reye’s syndrome began in 1973.

- The peak annual incidence of 555 cases reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) was in 1979-1980.

- Cases of Reye’s syndrome declined in number after 1980, when the government began issuing warnings about the association between this syndrome and aspirin.

- Whereas an average of 100 cases per year were reported in 1985 and 1986, the maximum number of cases reported annually between 1987 and 1993 was 36, with a range of 0.03-0.06 cases per 100,000 per year.

- Since 1994, two or fewer cases have been reported every year.

- Seasonal occurrence initially peaked from December to April, which correlated with the peak occurrence of viral respiratory infections, particularly influenza.

- In the United Kingdom, 597 cases were reported between 1981 and 1996.

- After warnings of the association between Reye’s syndrome and aspirin were issued in 1986, the incidence of Reye’s syndrome decreased substantially, from a high of 0.63 per 100,000 children younger than 12 years in 1983-1984 to 0.11 cases per 100,000 in 1990-1991.

- Of the 597 cases, 155 were later reclassified, 76 of them as involving an IEM.

- Based on US CDC surveillance statistics for 1980-1997 for patients younger than 18 years, 1207 cases were reported in the United States.

- Incidence peaks between age 5 and 14 years (median, 6 years; mean, 7 years); 13.5% were younger than 1 year.

- The racial distribution of Reye’s syndrome is 93% white and 5% African American, with the remaining percentage Asian, American Indian, and Native Alaskan.

Causes

The causes of Reye’s syndrome include the following:

- Pathogens. Influenza virus types A and B and varicella-zoster virus are the pathogens most commonly associated with Reye’s syndrome.

- Salicylates. Less than 0.1% of children who took aspirin developed Reye’s syndrome, but more than 80% of patients diagnosed with Reye’s syndrome had taken aspirin in the past 3 weeks.

- Inborn errors of metabolism. IEMs that produce Reye-like syndromes include fatty-acid oxidation defects, particularly medium-chain acyl dehydrogenase (MCAD) and long-chain acyl dehydrogenase deficiency (LCAD) inherited and acquired forms, urea-cycle defects, amino and organic acidopathies, primary carnitine deficiency, and disorders of carbohydrate metabolism.

Clinical Manifestations

Signs and symptoms of Reye’s syndrome include:

- Vomiting. Protracted vomiting is seen in patients with or without clinically significant dehydration.

- Hepatomegaly. There is enlargement of the liver and development in fatty acids which occur in 50% of patients.

- Lethargy. There is unusual sleepiness or lethargy progressing to encephalopathy.

The CDC uses the Hurwitz classification but adds stage 6. The stages used in the CDC classification of Reye’s syndrome are as follows:

- Stage 0. Alert, abnormal history and laboratory findings consistent with Reye’s syndrome, and no clinical manifestations.

- Stage 1. Vomiting, sleepiness, and lethargy.

- Stage 2. Restlessness, irritability, combativeness, disorientation, delirium, tachycardia, hyperventilation, dilated pupils with sluggish response, hyperreflexia, positive Babinski sign, and appropriate response to noxious stimuli.

-

Stage 3. Obtunded, comatose, decorticate rigidity, and inappropriate response to noxious stimuli.

-

Stage 4. Deep coma, decerebrate rigidity, fixed and dilated pupils, loss of oculovestibular reflexes, and dysconjugate gaze with caloric stimulation.

-

Stage 5. Seizures, flaccid paralysis, absent deep tendon reflexes (DTRs), no pupillary response, and respiratory arrest.

-

Stage 6. Patients who cannot be classified because they have been treated with curare or another medication that alters the level of consciousness.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

Workup to exclude inborn errors of metabolism (IEMs) must be performed and should include evaluation for defects of fatty-acid oxidation, amino and organic acidurias, urea-cycle defects, and disorders of carbohydrate metabolism.

- Ammonia levels. An ammonia level as high as 1.5 times normal 24-48 hours after the onset of mental status changes is the most frequent laboratory abnormality.

- ALT and AST levels. Levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) increase to 3 times normal but may return to normal by stages 4 or 5.

- Bilirubin levels. Bilirubin levels are higher than 2 mg/dL (but usually lower than 3 mg/dL) in 10-15% of patients; if the direct bilirubin level is more than 15% of total or if the total bilirubin level exceeds 3 mg/dL, consider other diagnoses.

- PT and aPTT levels. Prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) are prolonged more than 1.5-fold in more than 50% of patients.

- Glucose levels. Glucose, while usually normal, may be low, particularly during stage 5 and in children younger than 1 year.

- Lumbar puncture. If the patient is hemodynamically stable and shows no signs of increased intracranial pressure (ICP); opening pressure may or may not be increased; the white blood cell (WBC) count in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is 8/µL or fewer.

Medical Management

No specific treatment exists for Reye syndrome; supportive care is based on the stage of the syndrome.

- Stage 0-1. Keep the patient quiet; frequently monitor vital signs and laboratory values; correct fluid and electrolyte abnormalities, hypoglycemia, and acidosis; maintain electrolytes, serum pH, albumin, serum osmolality, glucose, and urine output in normal ranges; consider restricting fluids to two-thirds of maintenance; overhydration may precipitate cerebral edema use colloids (eg, albumin) as necessary to maintain intravascular volume.

- Stage 2. The standard of care consists of continuous cardiorespiratory monitoring, placement of central venous lines or arterial lines to monitor hemodynamic status, urine catheters to monitor urine output, ECG to monitor cardiac function, and EEG to monitor seizure activity; prevent increased ICP; elevate the head to 30°, keep the head in a midline orientation, use isotonic rather than hypotonic fluids, and avoid overhydration.

- Stage 3-5. Continuously monitor ICP, central venous pressure, arterial pressure, or end-tidal carbon dioxide; perform endotracheal intubation if the patient is not already intubated.

Pharmacologic Management

No specific treatment is available for Reye syndrome.

- Urea cycle disorder treatment agents. Ammonia detoxicants are used for the treatment of hyperammonemia; they enhance the elimination of nitrogen; sodium phenylacetate–sodium benzoate is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of hyperammonemia due to urea-cycle defects and is available only from a specialty wholesaler, Ucyclyd Pharma, Inc.

- Antiemetic agents. Antiemetic agents such as ondansetron are administered to decrease vomiting and during the initiation of sodium phenylacetate–sodium benzoate therapy.

Nursing Management

Nursing management for the patient with Reye’s syndrome includes:

Nursing Assessment

Assessment findings for Reye’s syndrome:

- Stage 1. Lethargy, vomiting, and hepatic dysfunction.

- Stage 2. Hyperventilation, hyperactive reflexes, delirium, and hepatic dysfunction.

- Stage 3. Coma, decorticate rigidity, hyperventilation and hepatic dysfunction.

- Stage 4. Deepening coma, large fixed pupils, decerebrate rigidity, and minimal hepatic dysfunction

- Stage 5. Seizures, flaccidity, loss of deep tendon reflexes, and respiratory arrest (death is usually a result of cerebral edema or cardiac arrest).

Nursing Diagnosis

Based on the assessment data, the major nursing diagnoses are:

- Deficient fluid volume related to failure of regulatory mechanism.

- Ineffective cerebral tissue perfusion related to diminished arterial or venous blood flow and hypovolemia.

- Risk for trauma related to generalized weakness, reduced coordination, and cognitive deficits.

- Reduced breathing pattern related to decreased energy and fatigue, cognitive impairment, tracheobronchial obstruction, and inflammatory process.

Nursing Care Planning and Goals

The major goals for the patient are:

- The patient will maintain adequate ventilation.

- The patient will maintain a normal respiratory status, as evidenced by normal respiratory rate.

- The patient will maintain orientation to environment without evidence of deficit.

- The patient will maintain skin integrity.

- The patient will maintain joint mobility and range of motion.

Nursing Interventions

Nursing interventions for the patient are:

- Check oxygenation status. Monitor vital signs and pulse oximetry to determine oxygenation status.

- Monitor ICP. Monitor ICP with a subarachnoid screw or other invasive device to closely assess for increased ICP.

- Keep track of the blood glucose levels. Monitor blood glucose levels to detect hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia and prevent complications.

- Assess I&O. Monitor fluid intake and output to prevent fluid overload.

- Assess the overall patient status. Assess cardiac, respiratory, and neurologic status to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions and monitor for complications such as seizures.

- Check cardiopulmonary status. Assess pulmonary artery catheter pressures to assess cardiopulmonary status.

- Position the patient appropriately. Keep the head of the bed at a 30-degree angle to decrease ICP and promotes venous return.

- Observe seizure precaution. Maintain seizure precautions to prevent injury.

- Establish oxygen therapy. Maintain oxygen therapy, which may include intubation and mechanical ventilation, to promote oxygenation and maintain thermoregulation.

- Provide medications. Administer medications as ordered and monitor for adverse effects to detect complications.

- Transfuse blood products. Administer blood products as ordered to increase the oxygen-carrying of blood and prevent hypovolemia.

- Check for neuro problems. Check for loss of reflexes and signs of flaccidity to determine the degree of neurologic involvement.

- Monitor the patient’s temperature. Provide a hypothermia blanket as needed and monitor the client’s temperature every 15 to 30 minutes while the blanket is in use to prevent injury and maintain thermoregulation.

- Provide postoperative care. Provide postoperative craniotomy care if necessary to promote wound healing and prevent complications.

- Prevent impaired skin integrity. Provide good skin and mouth care and perform ROM exercises to prevent alteration in skin integrity and to promote joint motility.

- Support the patient and the family. Be supportive of the family and keep them informed of the patient’s status to decrease anxiety.

Evaluation

The goals are met as evidenced by:

- The patient maintained adequate ventilation.

- The patient maintained a normal respiratory status, as evidenced by normal respiratory rate.

- The patient maintained orientation to the environment without evidence of deficit.

- The patient maintained skin integrity.

- The patient maintained joint mobility and range of motion.

Documentation Guidelines

Documentation for the patient includes:

- Assessment findings, including the degree of deficit and current sources of fluid intake.

- I&O, fluid balance, changes in weight, presence of edema, urine specific gravity, and vital signs.

- Results of diagnostic studies.

- Past and recent history of injuries, awareness of safety needs.

- Use of safety equipment or procedures.

- Plan of care.

- Teaching plan.

- Client’s responses to interventions, teaching, and actions performed.

- Attainment or progress toward desired outcomes.

- Modifications to plan of care.

Leave a Comment