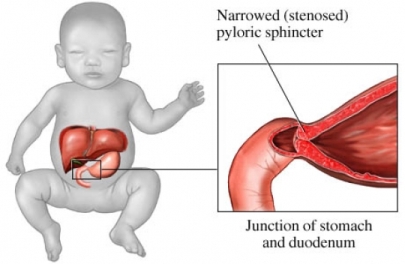

Pyloric stenosis is a relatively common gastrointestinal disorder among infants that occurs when the muscle at the lower end of the stomach (pylorus) thickens, leading to the narrowing of the passage between the stomach and the small intestine. The result is frequent vomiting, dehydration, and failure to thrive in affected infants.

This nursing note aims to explain pyloric stenosis from a nursing perspective, emphasizing the importance of vigilant monitoring, patient and family education, and collaborative efforts with the healthcare team to ensure positive health outcomes for infants living with this potentially serious condition.

What is Pyloric Stenosis?

Pyloric stenosis, also known as infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis (IHPS), is the most common cause of intestinal obstruction in infancy.

- Pyloric stenosis is characterized by hypertrophy of the circular muscle fibers of the pylorus, with a severe narrowing of the lumen.

- The pylorus is thickened to as much as twice its size, is elongated, and has a consistency resembling cartilage; as a result of this obstruction at the distal end of the stomach, the stomach becomes dilated.

Pathophysiology

In 1717, Blair first reported autopsy findings of pyloric stenosis.

- Marked hypertrophy and hyperplasia of the 2 (circular and longitudinal) muscular layers of the pylorus occur, leading to the narrowing of the gastric antrum.

- The pyloric canal becomes lengthened, and the whole pylorus becomes thickened.

- The mucosa is usually edematous and thickened; in advanced cases, the stomach becomes markedly dilated in response to near-complete obstruction.

Statistics and Incidences

The incidence of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis is 2-4 per 1000 live births.

- Death from infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis is rare and unexpected; the reported mortality rate is very low and usually results from delays in diagnosis with eventual dehydration and shock.

- Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis is more common in whites than Hispanics, blacks, or Asians; the incidence is 2.4 per 1000 live births in whites, 1.8 in Hispanics, 0.7 in blacks, and 0.6 in Asians.

- Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis has a male-to-female predominance of 4-5:1, with 30% of patients with infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis being first-born males.

- The usual age of presentation is approximately 2 – 6 weeks of life.

- Approximately 95% of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis cases are diagnosed in those aged 3-12 weeks.

Causes

The causes of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis are multifactorial.

- Exposure to antibiotics. A cohort study found that the treatment of young infants with macrolide antibiotics was strongly associated with infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis (IHPS).

- Genetic factors. A nationwide study of nearly 2 million Danish children born between 1977 and 2008 shows strong evidence for familial aggregation and heritability of pyloric stenosis.

- Nitric oxide. Impairment of this neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) synthesis has been implicated in infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis, in addition to achalasia, diabetic gastroparesis, and Hirschsprung disease.

Clinical Manifestations

Pyloric stenosis is rarely symptomatic during the first days of life; it has occasionally been recognized shortly after birth, but the average affected infant does not show symptoms until about the third week of life.

- Vomiting. Classically, the infant with pyloric stenosis has non bilious vomiting or regurgitation, which may become projectile (in as many as 70% of cases), after which the infant is still hungry.

- Jaundice. The infant may develop jaundice, which is corrected upon correction of the disease.

- Dehydration and malnutrition. As the obstruction becomes more severe, the infant begins to show signs of dehydration and malnutrition, such as poor weight gain, weight loss, marasmus, decreased urinary output, lethargy, and shock.

- Palpable pylorus. In as many as 60-80% of the infants with infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis (IHPS), a firm, non-tender, and mobile hard pylorus that is 1-2 cm in diameter, described as an “olive,” may be present in the right upper quadrant at the lateral edge of the rectus abdominis muscle.

- Gastric peristalsis. Clinicians may also observe gastric peristalsis just prior to emesis as the peristaltic waves try to overcome the obstruction.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

Diagnosis is usually made on the clinical evidence.

- Laboratory studies. Electrolytes, pH, BUN, and creatinine levels should be obtained at the same time as intravenous access in patients with pyloric stenosis.

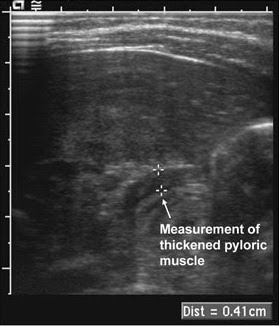

- Ultrasonography. If the clinical presentation is typical and an olive is felt, the diagnosis is almost certain; however formal ultrasonography is still recommended to evaluate the pylorus and confirm the diagnosis.

- Radiography. Radiographic studies with barium swallow show an abnormal retention of barium in the stomach and increased peristalsis.

Medical Management

Treatment of a child with pyloric stenosis includes:

- Prehospital care. As with all pediatric resuscitations, prehospital care in patients with pyloric stenosis should be consistent with pediatric advanced life support (PALS) recommendations for infants who are dehydrated or in shock.

- Correction of dehydration. If significant dehydration has occurred, immediate treatment requires correction of fluid loss, electrolytes, and acid-base imbalance, starting with an initial fluid bolus (20ml/kg) of isotonic crystalloid.

- Diet. Feeding can be initiated 4-8 hours after recovery from anesthesia, although earlier feeding has been studied; infants who are fed earlier than 4 hours do not have a worse total clinical outcome; however, they do vomit more frequently and more severely, leading to significant discomfort for the patient and anxiety for the parents.

- Pyloromyotomy. A surgical procedure called a pyloromyotomy, also known as a Fredet-Ramstedt operation, is the treatment of choice.

Pharmacologic Management

Medications used to treat pyloric stenosis symptomatically are:

- IV atropine. The intravenous dose of atropine for the treatment of pyloric stenosis ranges in studies from 0.04 to 0.225mg/kg/day and is given for 1 – 10 days.

- Oral atropine. Oral atropine (0.08 – 0.45mg/kg/day) is continued, after IV therapy has been deemed successful, for 3 weeks to 4 months.

Nursing Management

Nursing management in a child with pyloric stenosis include:

Nursing Assessment

Assessment in a child with pyloric stenosis include:

- Assess the child’s history of vomiting. Ask when the vomiting started and determine the character of the vomiting.

- Assess for the child’s elimination. Ask the caregiver about constipation and scanty urine.

- Physical exam. Physical exam reveals an infant who may show signs of dehydration; obtain the infant’s weight and observe skin turgor and skin condition, anterior fontanelle, temperature, apical pulse rate, irritability, lethargy, urine, lips and mucous membranes of the mouth, and eyes; observe for visible gastric peristalsis when the infant is eating.

Nursing Diagnoses

Based on the assessment data, the major nursing diagnoses are:

- Imbalanced nutrition: less than body requirements related to inability to retain food.

- Deficient fluid volume related to frequent vomiting.

- Impaired oral mucous membrane related to NPO status.

- Risk for impaired skin integrity related to fluid and nutritional deficit.

- Compromised family coping related to seriousness of illness and impending surgery.

Nursing Care Planning and Goals

The major nursing care planning goals for a child with pyloric stenosis are:

- Improving nutrition and hydration.

- Maintaining mouth and skin integrity.

- Relieving family anxiety.

Nursing Interventions

- Maintain adequate nutrition and fluid intake. If the infant is severely dehydrated and malnourished, rehydration with intravenous fluid and electrolytes are necessary; feedings of formula thickened with infant cereal and fed through a large-holed nipple may be given to improve nutrition; feed the infant slowly while he or she is sitting in an infant seat or being held upright.

- Provide mouth care. The infant needs good mouth care as the mucous membranes of the mouth may be dry because of dehydration and the omission of oral fluids before surgery; a pacifier can satisfy the baby’s need for sucking because of the interruption in normal feeding and sucking habits.

- Promote skin integrity. The infant is repositioned, the diaper is changed, and lanolin or A and D ointment is applied to dry skin areas.

- Promote family coping. Include the caregivers in the preparation for surgery and explain the importance of added IV fluids, the reason for ultrasonographic or barium swallow examination, and the function of the NG tube and saline lavage; describe the surgical procedure to be performed; and explain what to expect and how long the operation will last.

Evaluation

Goals are met as evidenced by:

- Improved nutrition and hydration.

- Maintained mouth and skin integrity.

- Relieved family anxiety.

Documentation Guidelines

Documentation in a child with pyloric stenosis includes:

- Individual findings include factors affecting, interactions, the nature of social exchanges, and specifics of individual behavior.

- Intake and output.

- Characteristics of vomitus.

- Cultural and religious beliefs, and expectations.

- Plan of care.

- Teaching plan.

- Responses to interventions, teaching, and actions performed.

- Attainment or progress toward the desired outcome.

Leave a Comment