This nursing management guide for diabetes aims to provide a clear, evidence-based understanding of the disease. It emphasizes the importance of early detection, patient education, lifestyle management, and nursing care throughout the lifespan, with special considerations for pediatric and geriatric populations.

What is Diabetes Mellitus?

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a chronic metabolic disorder characterized by elevated blood glucose levels (hyperglycemia) resulting from problems with insulin secretion, insulin action, or both. Insulin, a hormone produced by the pancreas, enables the facilitation of entry of glucose into cells for energy. When insulin is absent, insufficient, or ineffective, glucose accumulates in the bloodstream, leading to long-term damage to various organ systems.

Diabetes is a growing global health crisis, affecting an estimated 589 million adults worldwide in 2024, with Type 2 diabetes making up over 90% of cases. Once seen primarily in adults, it is now rising in children and adolescents as well.

It is a major contributor to blindness, kidney failure, heart disease, stroke, and amputations, and ranks as the 8th leading cause of death in the U.S. Despite advances in care, the global burden remains high.

Classification and Types of Diabetes

Several types of diabetes are recognized, with the most common being Type 1 diabetes (T1DM) and Type 2 diabetes (T2DM). Other specific forms of diabetes include those caused by genetic defects (e.g., Maturity-Onset Diabetes of the Young, or MODY, pancreatic diseases, or drug-induced diabetes. These are less common but important for comprehensive classification.

Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM)

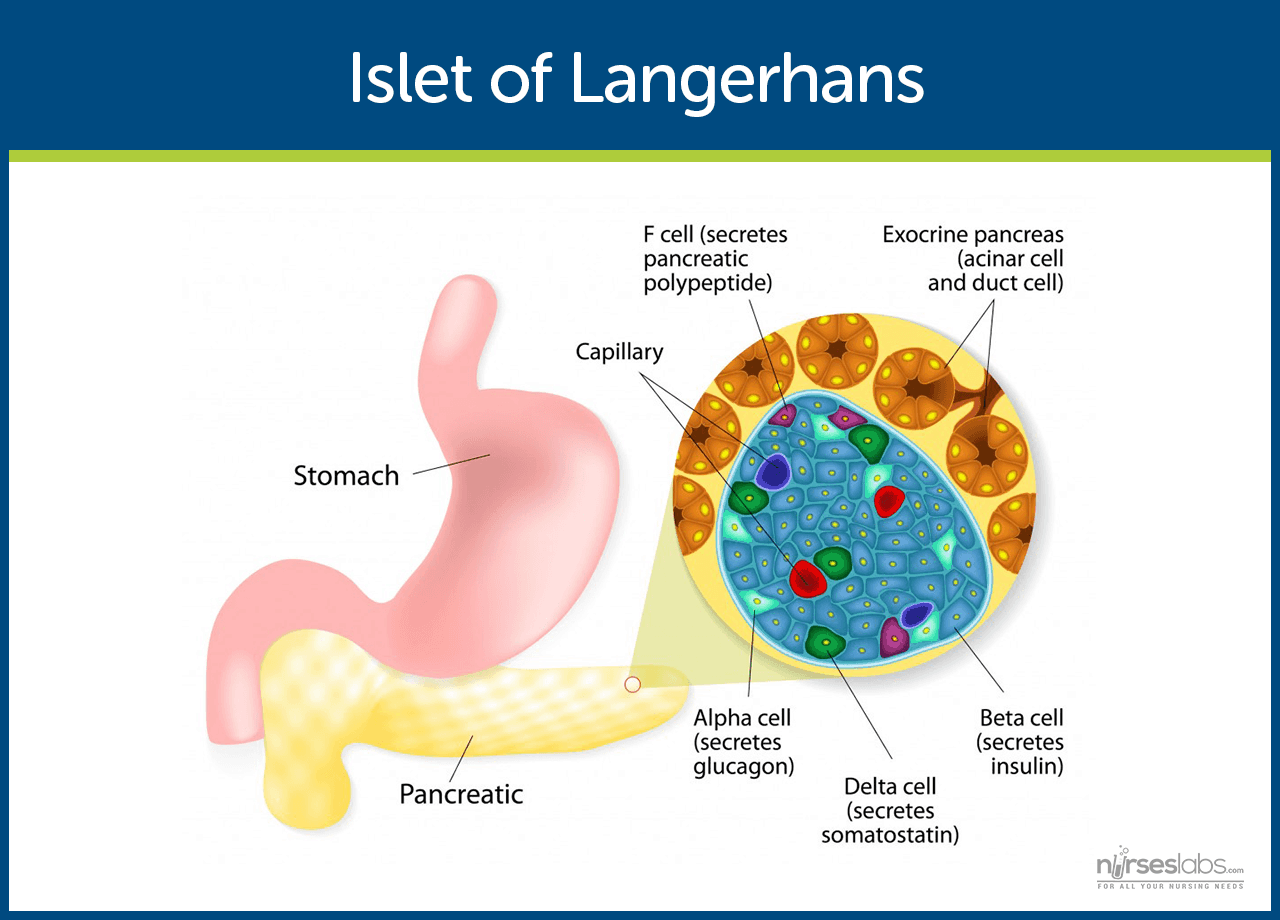

Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disorder in which the immune system attacks and destroys the insulin-producing beta cells of the pancreas. This leads to an absolute insulin deficiency, where the pancreas produces little to no insulin, resulting in dangerously high blood sugar levels unless treated with exogenous insulin.

T1DM often has an abrupt onset and typically presents in childhood or adolescence, formerly referred to as “juvenile diabetes” or insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. It can also appear in adulthood, where it may be misdiagnosed as type 2. The exact cause is unclear, but genetic susceptibility and environmental triggers (like certain viral infections) are thought to play significant roles. Currently, there is no known way to prevent type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM). Lifelong insulin therapy is required for survival and management.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM)

Type 2 diabetes accounts for more than 90% of diabetes cases globally. It is characterized by insulin resistance, where the body does not use insulin effectively, and a relative insulin deficiency, as the pancreas fails to meet increased insulin demand. Blood glucose levels rise gradually, often going unnoticed for years.

Type 2 diabetes commonly develops in adulthood, though rising obesity rates have led to earlier onset in adolescents. Risk factors include obesity, physical inactivity, unhealthy diet, and genetics. Management begins with lifestyle modifications and oral medications, progressing to insulin or injectable therapies over time. Unlike type 1, insulin may not be required at diagnosis.

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM)

Gestational diabetes (GDM) is a form of glucose intolerance first identified during pregnancy, usually in the second or third trimester. Hormonal changes lead to increased insulin resistance in pregnant individuals, and if insulin production cannot meet this demand, hyperglycemia occurs.

GDM often resolves after childbirth, but it increases the risk of developing type 2 diabetes later in life. Management during pregnancy focuses on maintaining blood glucose levels within target ranges through diet, monitoring, and, in some cases, insulin therapy. Postpartum follow-up is needed to assess glucose regulation.

Maturity-Onset Diabetes of the Young (MODY)

MODY is a rare, genetically inherited form of diabetes caused by a mutation in a single gene affecting insulin production. It usually appears in adolescence or early adulthood and may be mistaken for type 1 or type 2 diabetes. Unlike type 1 diabetes, it typically does not require insulin and may respond well to oral hypoglycemic agents.

Pancreatogenic Diabetes (Type 3c)

Pancreatogenic diabetes results from damage to the pancreas due to conditions like chronic pancreatitis, pancreatic cancer, or surgical removal of the pancreas. It leads to both exocrine and endocrine dysfunction, impairing the production of insulin and digestive enzymes. Management includes insulin therapy and enzyme replacement.

Drug- or Chemical-Induced Diabetes

Certain medications, such as corticosteroids, antipsychotics, and immunosuppressants, can impair insulin action or secretion, leading to hyperglycemia. This form of diabetes may be temporary or permanent, depending on the duration of the drug and the underlying predisposition. Glucose levels typically return to normal if the causative agent is discontinued early.

Prediabetes

Prediabetes is a condition where blood glucose levels are elevated but not yet high enough for a diabetes diagnosis. It increases the risk of developing type 2 diabetes and heart disease, but lifestyle changes like weight loss, healthy eating, and exercise can help reverse or delay it. Diagnostic markers include FPG 100–125 mg/dL, 2h OGTT 140–199 mg/dL, or A1C 5.7–6.4%.

Epidemiology and Global Impact

Diabetes is a growing global health concern, with both prevalence (existing cases) and incidence (new cases) on the rise. Key statistics include

Global prevalence

As of 2025, approximately 1 in 9 adults worldwide has diabetes. The International Diabetes Federation estimates 589–590 million adults (20–79 years) will be living with diabetes in 2024, and this number is projected to rise to 853 million by 2050 if current trends continue. This dramatic increase is primarily driven by type 2 diabetes, due to population aging, urbanization, increasing obesity, sedentary lifestyles, and dietary changes. Over 80% of adults with diabetes live in low- and middle-income countries, where rapid lifestyle shifts and limited healthcare resources pose challenges in diabetes prevention and care.

Diabetes in the U.S. Population

In 2021, around 38.4 million Americans (11.6% of the population) were living with diabetes. Of these, 28.5 million were diagnosed, while 8.7 million were undiagnosed. Nearly one-third of adults aged ≥65 had diabetes. Approximately 1.2 million new cases occur annually. Minority populations, such as American Indian/Alaska Natives and non-Hispanic Black adults, experience higher prevalence, influenced by genetic and social determinants of health.

Type 1 and Youth-Onset Type 2 Diabetes

Type 1 remains the predominant form of diabetes in children and adolescents. In the U.S., about 2 million individuals have type 1, including 304,000 under the age of 20. Each year, approximately 18,000 new pediatric cases of type 1 diabetes and 5,000 cases of type 2 diabetes are reported. Youth-onset type 2 is especially rising among obese teens in minority populations. Globally, about 9 million individuals are living with type 1 diabetes, with a growing number of diagnoses in adults.

Morbidity and mortality

Diabetes significantly contributes to premature illness and death through vascular complications. In 2021, diabetes caused an estimated 1.6 million deaths globally. Including deaths from related cardiovascular and kidney complications, the total exceeds 2 million annually. Nearly half of diabetes-related deaths occur before age 70. In the U.S., diabetes was the 8th leading cause of death, implicated in over 103,000 death certificates.

Economic impact

Diabetes presents a significant financial burden due to healthcare costs and productivity losses. The U.S. spent over $400 billion on diagnosed diabetes by 2022, with diabetic patients incurring more than twice the healthcare costs of non-diabetics. Worldwide, diabetes-related expenditures exceed $1 trillion annually.

Diabetes-Related Complications

Diabetes is a leading cause of complications. Diabetes is a leading cause of end-stage renal disease, blindness due to diabetic retinopathy, and non-traumatic lower-limb amputations. It significantly increases cardiovascular disease risk; diabetic adults are twice as likely to experience heart attacks or strokes. However, improved glucose control, regular screenings, and comprehensive care have helped reduce some complication rates.

Causes and Risk Factors

The exact cause of diabetes mellitus is unknown; however, certain factors contribute to its development.

Type 1 Diabetes

An autoimmune attack on the insulin-producing cells of the pancreas causes type 1 diabetes. Risk factors include genetics, family history, and possible viral or environmental triggers.

- Autoimmune Reaction. The body’s immune system mistakenly attacks and destroys the insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas. This leads to a gradual loss of insulin, causing hyperglycemia.

- Genetic Susceptibility. Individuals with specific genetic markers, particularly HLA-DR3 and HLA-DR4, are at an increased risk of developing the condition. However, having these genes does not guarantee the development of type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM).

- Family History. Although not always present, a family history of type 1 diabetes slightly raises the risk. First-degree relatives of people with T1DM have a higher likelihood of developing the disease.

- Environmental Triggers. Exposure to viruses such as enteroviruses or Coxsackie B may initiate the autoimmune response. Other factors, such as early exposure to cow’s milk or a lack of vitamin D, are also being investigated.

- Presence of Autoantibodies. Autoantibodies targeting pancreatic islet cells (e.g., GAD65, insulin, IA-2) appear before symptoms manifest. These indicate an active autoimmune process and can be used for early diagnosis or screening.

Type 2 Diabetes

T2DM has a strong lifestyle and behavioral component along with genetic predisposition. The primary metabolic defects are insulin resistance (the body’s cells do not respond well to insulin) and relative insulin deficiency (the pancreas cannot keep up with insulin demand). Major risk factors for type 2 include:

- Insulin Resistance. Insulin resistance occurs when body cells, particularly in the muscles, liver, and fat, fail to respond adequately to insulin. This forces the pancreas to produce more insulin to maintain normal glucose levels, ultimately leading to elevated blood sugar levels.

- Beta-Cell Dysfunction. Over time, pancreatic beta cells become unable to secrete enough insulin to overcome resistance. This decline in insulin secretion worsens hyperglycemia and is a hallmark of T2DM progression.

- Obesity (Especially Abdominal Obesity). Excess fat, especially around the abdomen, disrupts hormone signaling and promotes inflammation. This is a major driver of insulin resistance and a leading modifiable risk factor for type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).

- Sedentary Lifestyle. Lack of physical activity reduces insulin sensitivity and contributes to weight gain. Regular exercise improves glucose uptake by cells and supports metabolic health.

- Poor Dietary Habits. Diets high in refined carbohydrates, added sugars, and saturated fats increase the risk of insulin resistance and obesity. A nutrient-poor diet can accelerate the onset of diabetes in at-risk individuals.

- Unhealthy diet: Diets high in calories, processed carbohydrates and fats, and sugar-sweetened beverages can contribute to weight gain and metabolic abnormalities.

- Genetic Predisposition. Having a family history of type 2 diabetes significantly raises one’s risk. Specific genes influence insulin production, fat storage, and glucose metabolism.

- Age and ethnicity. As people age, beta-cell function declines and insulin resistance increases, raising the risk of T2DM, particularly after age 45, especially in individuals who are inactive or experience weight gain. Certain ethnic groups (e.g., African Americans, Hispanics, Asians) are also more susceptible due to genetic and environmental factors.

- History of gestational diabetes or prediabetes. Women who had diabetes during pregnancy are at increased risk of developing T2DM later in life. This indicates a predisposition to insulin resistance.

- Other medical conditions: Conditions like polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) or acanthosis nigricans (a skin condition) are associated with insulin resistance and higher diabetes risk. Chronic use of certain medications (e.g., glucocorticoids, some antipsychotics) can also predispose to type 2.

Gestational Diabetes

Gestational diabetes is caused by pregnancy-related hormonal changes that increase insulin resistance. Risk factors include obesity, advanced maternal age, family history of diabetes, and previous GDM or large babies.

- Hormonal Changes During Pregnancy. Placental hormones like human placental lactogen (hPL), estrogen, and cortisol increase during pregnancy, causing insulin resistance. This reduces the mother’s ability to use insulin effectively, leading to elevated blood glucose levels, especially in the second and third trimesters.

- Obesity or Overweight. Excess body fat, particularly central adiposity, contributes to increased insulin resistance. Women who are overweight or obese before pregnancy have a significantly higher risk of developing gestational diabetes.

- Advanced Maternal Age. Women over the age of 25–30 have a higher risk of developing GDM. This is partly due to an age-related decline in insulin sensitivity.

- Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS). PCOS is associated with insulin resistance and hormonal imbalances. Women with PCOS are at increased risk of developing GDM during pregnancy.

- Ethnicity. Certain ethnic groups, such as Hispanic, African American, Native American, South or Southeast Asian, and Pacific Islander women, have a higher risk for GDM. This is believed to be due to a combination of genetic and lifestyle factors.

- Family History and History of GDM. A family history of type 2 diabetes or previous gestational diabetes increases the risk of GDM. These factors suggest a genetic predisposition and a higher chance of developing type 2 diabetes later.

- Previous Macrosomic Baby. Giving birth to a baby weighing more than 4,000 grams (8 lbs. 13 oz.) in a prior pregnancy is a risk factor. It suggests prior unrecognized glucose intolerance or undiagnosed GDM.

Pathophysiology

Normal Glucose Homeostasis. Glucose is the body’s primary energy source, regulated by insulin. After meals, insulin facilitates glucose uptake into cells and inhibits the production of glucose in the liver. It promotes glycogen and fat storage while preventing the breakdown of protein and fat. During fasting, insulin levels drop, and the liver releases or synthesizes glucose to maintain normal fasting glucose levels (70–100 mg/dL). Diabetes disrupts this balance.

Type 1 Diabetes Pathophysiology.

In type 1 diabetes, autoimmune destruction of beta cells causes absolute insulin deficiency. Once 80–90% of beta cells are lost, the pancreas can’t produce enough insulin. As a result, cells can’t take up glucose, leading to hyperglycemia and cellular “starvation” despite high blood glucose levels.

Autoimmune Destruction of Pancreatic Beta Cells

Type 1 diabetes begins with an autoimmune reaction in which the body’s immune system mistakenly targets and destroys the insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas. T-lymphocytes primarily mediate this and are often triggered by genetic susceptibility combined with environmental factors (e.g., viral infections). As beta-cell mass declines, insulin production decreases progressively, eventually leading to complete deficiency.

Absolute Insulin Deficiency

Insulin is essential for facilitating glucose uptake into muscle and adipose tissue. With the loss of beta cells, there is an absolute lack of endogenous insulin, causing glucose to accumulate in the bloodstream (hyperglycemia). Without insulin, body cells cannot use glucose for energy, despite its abundance in the blood.

Impaired Cellular Glucose Uptake

In the absence of insulin, glucose cannot enter insulin-dependent cells, particularly muscle and fat cells. This results in cellular energy starvation, even as blood glucose levels remain elevated. As a result, the body activates alternative energy sources, such as fat and protein catabolism.

Increased Lipolysis and Ketone Formation

To meet energy demands, the body breaks down stored fat into free fatty acids through lipolysis. These fatty acids are transported to the liver and converted into ketone bodies, which serve as an alternative fuel, especially for the brain. However, excess ketone production overwhelms the body’s buffering system, leading to metabolic acidosis (diabetic ketoacidosis).

Osmotic Diuresis and Fluid Loss

When blood glucose exceeds the renal threshold (~180 mg/dL), the kidneys are unable to reabsorb all the filtered glucose, leading to glycosuria. Glucose in the urine exerts an osmotic pull, drawing water with it and resulting in polyuria (frequent urination). This fluid loss leads to dehydration and triggers intense thirst (polydipsia).

Electrolyte Depletion and Imbalance

Osmotic diuresis also causes the loss of important electrolytes such as sodium and potassium in the urine. Although serum potassium levels may initially appear normal or elevated due to extracellular shifting, total body stores become depleted. This depletion can impair muscle and cardiac function and may become life-threatening if not corrected.

Muscle Wasting and Protein Breakdown

In the insulin-deficient state, the body also breaks down muscle proteins to provide substrates for gluconeogenesis. This process contributes to unintentional weight loss and general weakness. In children and adolescents, it may also impair normal growth and development.

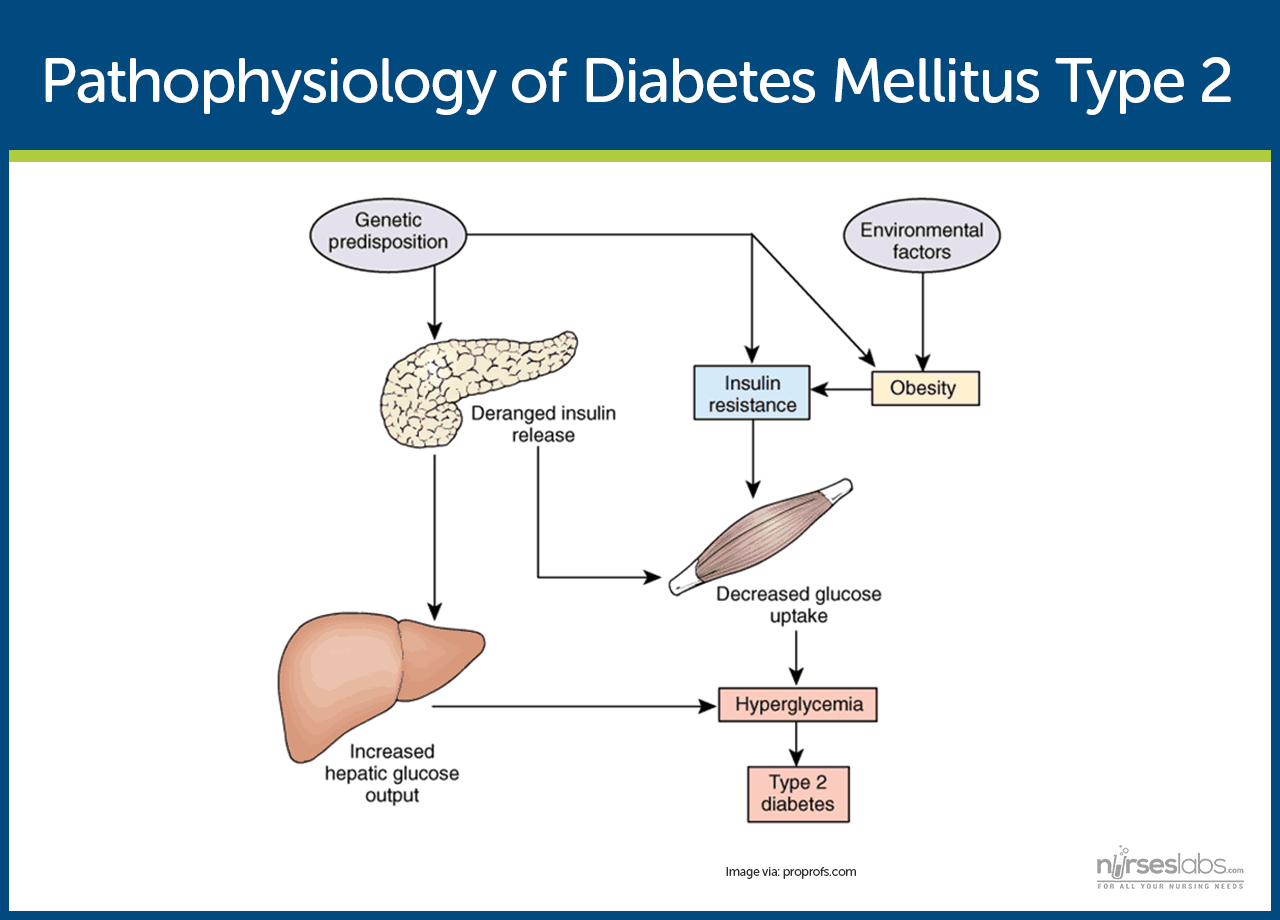

Type 2 Diabetes Pathophysiology

Type 2 diabetes mellitus is primarily caused by insulin resistance in muscle, fat, and liver cells, leading to reduced glucose uptake despite the presence of insulin. Over time, pancreatic beta cells become dysfunctional and fail to produce adequate insulin, resulting in persistent hyperglycemia.

Insulin Resistance

In type 2 diabetes, the body’s cells, particularly in muscle, fat, and liver, become less responsive to insulin. This resistance means glucose cannot effectively enter the cells, despite insulin being present. As a result, blood glucose levels rise, and the pancreas responds by producing more insulin in an attempt to compensate.

Compensatory Hyperinsulinemia

To overcome insulin resistance, the pancreas initially increases insulin production, a state known as hyperinsulinemia. This compensatory mechanism may keep blood glucose levels within the normal range for a time. However, sustained overproduction of insulin exhausts the beta cells and cannot be maintained long term.

Progressive Beta-Cell Dysfunction

Over time, pancreatic beta cells lose their ability to produce enough insulin, both in terms of quantity and timing. The first phase of insulin secretion (immediate release in response to glucose) is often impaired early in type 2 diabetes. As beta-cell function deteriorates further, insulin levels fall, and blood glucose becomes persistently elevated.

Increased Hepatic Glucose Production

The liver in type 2 diabetes often continues to produce glucose even when blood glucose is already high, a process called hepatic glucose overproduction. This is due in part to insulin resistance in liver cells, which fail to “sense” adequate insulin signals to suppress gluconeogenesis. This contributes to fasting hyperglycemia and worsens glycemic control.

Impaired Incretin Effect

Incretins are gut hormones (e.g., GLP-1 and GIP) that stimulate insulin secretion after eating. In type 2 diabetes, the incretin response is diminished, reducing postprandial insulin release and contributing to elevated glucose after meals. Additionally, GLP-1 degradation is increased, further impairing its regulatory effects.

Enhanced Lipolysis and Elevated Free Fatty Acids

Insulin resistance in adipose tissue leads to increased breakdown of fat (lipolysis) and elevated free fatty acid (FFA) levels in the bloodstream. Excess FFAs impair insulin signaling and promote inflammation, further worsening insulin resistance. FFAs also interfere with glucose uptake and contribute to liver fat accumulation (hepatic steatosis).

Chronic Inflammation and Oxidative Stress

Obesity, especially visceral fat, is associated with low-grade chronic inflammation that releases cytokines like TNF-α and IL-6. These inflammatory mediators disrupt insulin signaling pathways and contribute to both insulin resistance and beta-cell dysfunction. Oxidative stress also damages pancreatic beta cells, accelerating disease progression.

Genetic and Environmental Influences

Genetic predisposition plays a strong role in the development of type 2 diabetes, especially in individuals with a family history of the disease. Environmental and lifestyle factors such as physical inactivity, poor diet, and obesity further trigger insulin resistance and metabolic dysfunction. These combined factors ultimately lead to the clinical onset of diabetes.

In both type 1 and type 2 diabetes, chronic hyperglycemia causes damage through multiple mechanisms (e.g., the formation of advanced glycation end-products, oxidative stress in cells), leading to complications in the eyes, kidneys, nerves, and blood vessels. The hallmark of diabetes is a fasting blood glucose level of 126 mg/dL or higher, or any random glucose level of 200 mg/dL or higher, accompanied by symptoms, indicating that insulin is not adequately controlling blood sugar.

Clinical Manifestations

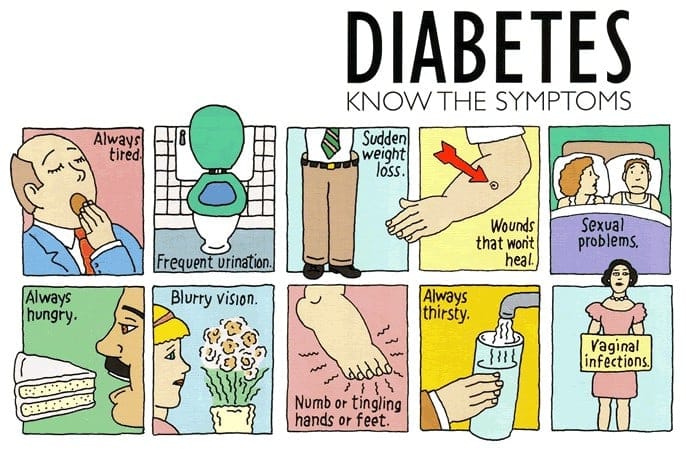

The hallmark symptoms of diabetes are primarily due to persistent hyperglycemia and its systemic effects. While there is considerable overlap between type 1 and type 2 diabetes, the onset, severity, and associated features can vary.

Classic Symptoms (Seen in Both Type 1 and Type 2)

- Polyuria (frequent urination). When blood glucose exceeds the renal threshold, glucose spills into the urine (glycosuria), drawing water with it, resulting in large volumes of dilute urine. Patients may report frequent daytime urination and nocturia. In children, this can present as new-onset enuresis, also known as bedwetting.

- Polydipsia (excessive thirst). Excessive urination leads to fluid loss and dehydration. The body responds by triggering constant thirst. Patients may drink large amounts of fluids but remain dehydrated.

- Polyphagia (increased hunger). Cells can’t use glucose without insulin, leading to energy starvation. This causes intense hunger, even with adequate or increased food intake. Weight loss may still occur, especially in type 1 diabetes.

- Weight loss. The body breaks down fat and muscle for energy when insulin is lacking. This results in noticeable weight loss despite increased appetite. It’s more common in type 1 diabetes and advanced type 2.

- General fatigue and weakness. Cells deprived of glucose can’t produce enough energy, causing fatigue. Dehydration worsens this weakness. Patients may feel tired and unable to perform everyday activities.

- Blurred vision. High blood glucose levels can cause lens swelling, leading to temporary changes in vision. Blurred or fluctuating vision usually improves with better glycemic control but may progress to retinopathy if untreated.

- Slow-healing wounds and frequent infections. Elevated glucose impairs immune response and blood flow. Patients may have slow-healing wounds and frequent infections like UTIs or skin rashes.

- Peripheral Neuropathy (Tingling/Numbness). Prolonged high glucose levels damage peripheral nerves. This leads to tingling, burning, or numbness in the hands and feet. It’s more common at diagnosis in type 2 diabetes.

- Irritability and mood changes. Children and adults may show increased irritability or mood swings. Poor concentration or behavioral changes can signal high blood sugar levels.

- No symptoms. Type 2 diabetes may develop without symptoms and go undetected. It is often found during routine tests or once complications arise. Early screening is vital in at-risk individuals.

In summary, the hallmark symptoms to remember are the “3 P’s”: Polyuria, Polydipsia, and Polyphagia. Unexplained weight loss and fatigue bolster suspicion of type 1, whereas overweight individuals with milder symptoms might have type 2. Any random blood glucose level≥200 mg/dL, accompanied by classic symptoms, is diagnostic of diabetes.

Diagnosis and Diagnostic Tests

Early detection of diabetes helps initiate timely management and prevent complications. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) defines specific criteria for diagnosing diabetes in non-pregnant adults (both apply to type 1 and type 2):

Fasting Plasma Glucose (FPG)

A fasting blood glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL (7.0 mmol/L) on at least two occasions is diagnostic. “Fasting” means no caloric intake for at least 8 hours. Normal fasting glucose is <100 mg/dL; 100–125 indicates prediabetes, and ≥126 indicates diabetes.

Glycated Hemoglobin (A1C) test

Hemoglobin A1C reflects average blood glucose over the past 2–3 months. An A1C of ≥6.5%, confirmed on repeat testing, indicates diabetes; 5.7–6.4% suggests prediabetes, and <5.7% is normal. It does not require fasting, but may be unreliable in cases of anemia or hemoglobin variants, and is not preferred for diagnosing acute-onset type 1 diabetes.

Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT)

In this test, the patient’s plasma glucose is measured after an overnight fast and again 2 hours after drinking a standardized 75 g glucose solution. A 2-hour glucose level of≥ 200 mg/dL indicates diabetes. The OGTT is more cumbersome but is very sensitive; it is often used to diagnose gestational diabetes or if other test results are borderline. A 2-hour value of 140–199 mg/dL is considered impaired glucose tolerance (prediabetes), and <140 is normal.

Random Plasma Glucose

A random blood glucose level ≥ 200 mg/dL with classic symptoms of diabetes (polyuria, polydipsia, unexplained weight loss, etc.) can establish a diagnosis. In a patient with apparent symptoms or a hyperglycemic crisis (such as DKA or HHS), a single random glucose measurement above this threshold is sufficient – waiting for a second test could be dangerous. In practice, this often applies to someone who presents very sick (e.g., a child in DKA) or an undiagnosed patient with obvious signs.

Nursing Note: If an initial test is in the diabetic range but the patient has no symptoms, guidelines advise repeating the same test on another day to confirm the diagnosis (to rule out lab error). However, if two different tests (such as FPG and A1C) are both above the diagnostic thresholds, that confirms the diagnosis as well. In symptomatic individuals, confirmation may not be needed before starting treatment.

Urine testing

A urine dipstick can detect glucose and ketones. Glucosuria indicates blood glucose >180 mg/dL, while ketonuria signals fat breakdown, typical in type 1 or poorly controlled type 2 diabetes. In children, both findings suggest type 1 and require urgent testing. Urinalysis can also detect microalbuminuria, an early sign of kidney damage.

Antibody tests

Autoantibody tests (e.g., GAD65, IA-2, ZnT8) help distinguish type 1 diabetes from type 2 or LADA, especially in adults or atypical cases. C-peptide levels can indicate how much insulin the body still produces, being low in type 1, normal in type 2, or high in early type 2. These tests are helpful when the type of diabetes is unclear.

Lipid profile

At diagnosis, especially in type 2 diabetes, a full lipid panel is essential. Patients often present with high triglycerides and low HDL levels due to insulin resistance, key features of metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular risk.

Baseline metabolic tests

Tests such as serum electrolytes, BUN, and creatinine help assess kidney function and hydration status. In cases of DKA or HHS, further testing, such as blood gases and serum osmolality, may reveal metabolic acidosis (characterized by a low pH and low bicarbonate levels) or severe dehydration.

Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c)

A baseline A1C gives an estimate of average blood glucose levels over the past 2–3 months. For example, an A1C of 10% indicates an average glucose of ~240 mg/dL and helps guide treatment planning.

Microalbuminuria screening

Type 2 diabetes patients should be screened at diagnosis for microalbuminuria, which signals early kidney damage. In type 1, screening begins 5 years after diagnosis or at puberty. A urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio >30 mg/g indicates microalbuminuria and may warrant renal-protective treatment like ACE inhibitors.

Dilated eye exam

A dilated eye exam is recommended shortly after a type 2 diagnosis and 3–5 years after a type 1 diagnosis to screen for retinopathy. By widening the pupils, it helps to examine the retina and blood vessels for damage closely.

Comprehensive foot exam

A comprehensive foot exam in diabetes checks for skin issues, deformities, infections, and circulation problems. It includes visual inspection, pedal pulse assessment, and sensory testing like monofilament and vibration tests. This helps detect risks early and prevent serious complications like ulcers or amputations.

Monofilament testing

A 10-gram monofilament (a thin nylon strand) is gently pressed against specific points on the sole until it bends. If the patient cannot feel the monofilament at one or more sites, it indicates peripheral neuropathy and an increased risk for foot ulcers and injuries.

Diagnostic criteria summary. For quick reference, diabetes may be diagnosed by any of the following (in a non-pregnant adult), preferably confirmed on a separate day if the patient is asymptomatic:

- Fasting plasma glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL.

- 2-hour OGTT glucose ≥ 200 mg/dL after 75 g glucose load.

- Hemoglobin A1C ≥ 6.5% (48 mmol/mol).

- Random plasma glucose ≥ 200 mg/dL with classic hyperglycemia symptoms or hyperglycemic crisis.

Summary of Diabetes Diagnostic Tests with their Normal and Abnormal Results.

| Test | Normal Results | Abnormal Results |

|---|---|---|

| Fasting Plasma Glucose (FPG) | < 100 mg/dL | 100–125 mg/dL = Prediabetes ≥126 mg/dL (on two occasions) = Diabetes |

| Hemoglobin A1C (Glycated Hemoglobin) | < 5.7% | 5.7–6.4% = Prediabetes ≥6.5% = Diabetes |

| Random Plasma Glucose | < 200 mg/dL (without symptoms) | ≥200 mg/dL with classic symptoms = Diabetes |

| Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT – 2 hours after 75g glucose) | < 140 mg/dL | 140–199 mg/dL = Prediabetes ≥200 mg/dL = Diabetes |

| Urine Testing | No glucose or ketones in urine | Glucosuria (glucose in urine) suggests blood glucose >180 mg/dL Ketonuria indicates fat breakdown, often seen in Type 1 or uncontrolled diabetes |

| Autoantibody and C-Peptide Tests | Negative antibodies; normal or high C-peptide | Positive antibodies (Type 1); low C-peptide = insulin deficiency |

| Lipid Profile | Triglycerides <150 mg/dL HDL >40 mg/dL (men) >50 mg/dL (women) | High triglycerides, low HDL = cardiovascular risk |

| Baseline HbA1c | <5.7% | ≥6.5%; higher = worse control |

| Microalbuminuria Screening | <30 mg/g (urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio) | 30 mg/g = early kidney disease |

| Dilated Eye Exam | No signs of diabetic retinopathy | Retinal damage (e.g., hemorrhages, exudates) |

| Comprehensive Foot Exam | Intact skin, normal pulses, full sensation | Negative antibodies, normal or high C-peptide |

| Monofilament Testing | Ulcers, infections, deformities, and poor circulation | Inability to feel = peripheral neuropathy risk |

Complications of Diabetes

Diabetes can affect virtually every organ system if not well controlled. Complications are generally divided into acute complications (immediate, short-term crises related to severe hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia) and chronic complications (long-term damage to organs from prolonged high blood sugar, often categorized into microvascular and macrovascular complications).

Acute Complications

Hypoglycemia (Low Blood Sugar)

One of the most common is hypoglycemia, which occurs when blood glucose falls below 70 mg/dL. It is usually caused by diabetes medications like insulin or sulfonylureas, especially when a patient skips meals, exercises more than usual, or takes too much medication.

- Symptoms. Sweating, shakiness, hunger, irritability, confusion; severe cases may lead to seizures or unconsciousness.

- Treatments and Nursing Management

- Administer 15g of Fast-Acting Carbohydrates, e.g., juice or glucose tablets. Rapidly raises blood glucose levels. Recheck blood sugar after 15 minutes and repeat if still <70 mg/dL.

- Administer Glucagon (IM/Subcutaneous) or IV Dextrose for Severe Cases. Used during emergencies when the patient is unconscious, seizing, or unable to take oral carbs. Glucagon stimulates the liver to release glucose; IV dextrose provides direct glucose.

- Monitor Blood Glucose Levels. Frequent glucose checks help confirm hypoglycemia and assess treatment response.

- Assess for Contributing Factors. Identify missed meals, excess insulin, or unexpected physical activity.

Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA)

Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA) is seen mainly in people with type 1 diabetes. DKA results from severe insulin deficiency and is marked by high blood glucose (usually between 250–600 mg/dL), ketone production, and metabolic acidosis (blood pH <7.3).

- Symptoms. Polyuria, polydipsia, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, fruity breath, Kussmaul breathing (rapid/deep), confusion, dehydration.

- Treatments and Nursing Management

- Intravenous (IV) Fluid Replacement. Initial fluids typically include isotonic saline (0.9% NaCl), followed by dextrose-containing solutions once glucose drops. Helps lower blood glucose by diluting excess sugar in the bloodstream.

- Insulin Therapy. Regular IV insulin lowers blood glucose, stops ketone production, and corrects acidosis. It must be closely monitored to avoid rapid glucose or potassium shifts.

- Monitor electrolytes, especially potassium. In DKA, insulin lowers potassium levels, risking hypokalemia, which can lead to cardiac arrhythmias. Potassium should be replaced as needed, even if initial levels appear normal.

Hyperglycemic Hyperosmolar State (HHS).

HHS occurs mainly in older adults with type 2 diabetes. Blood sugar levels can exceed 600 mg/dL without significant ketone production.

- Symptoms. Major symptoms of HHS include extreme hyperglycemia (>600 mg/dL), severe dehydration, altered mental status, and little to no ketone production. Patients may present with confusion, weakness, polyuria, and signs of fluid loss such as dry mucous membranes and low blood pressure.

- Treatments and Nursing Management

- IV Fluid Replacement. Rehydrates the body and restores perfusion. Helps dilute blood glucose and correct hyperosmolality.

- Insulin Therapy. Lowers blood glucose gradually to avoid rapid shifts. Helps stop further glucose production by the liver.

- Electrolyte Correction. Potassium and other electrolytes may drop with insulin therapy.

- Treat the Underlying Cause. Common triggers include infection, stroke, or missed medications. Antibiotics or supportive care may be needed.

Infections

Individuals with diabetes are more susceptible to infections, including urinary tract infections, pneumonia, and skin infections.

- Treatments and Nursing Management

- Administer Prescribed Antibiotics Promptly. Infections can worsen blood glucose control and trigger complications like DKA or HHS.

- Monitor Blood Glucose Closely. Infections increase insulin resistance and may raise glucose levels.

- Encourage Adequate Hydration. Fluids help manage fever and prevent dehydration, especially during infection.

- Implement Sick-Day Management Education. Teach patients to continue taking insulin even when not eating.

- Inspect and Care for Wounds Regularly. Diabetic wounds heal slowly and are prone to infection.

Chronic Complications

Chronic complications develop gradually from long-term exposure to high blood glucose levels. They affect both small (microvascular) and large (macrovascular) blood vessels, as well as the nervous system. Good glycemic control significantly reduces the risk of these complications.

Microvascular Complications

These involve damage to small blood vessels (capillaries) and typically appear after 5–10 years in type 1 diabetes, though they may already be present at diagnosis in type 2 due to delayed onset.

Diabetic Retinopathy (Eye Disease)

High glucose damages the retinal blood vessels, leading to vision changes or blindness. Early signs include microaneurysms and hemorrhages (non-proliferative stage), while advanced stages may involve new fragile vessels that can bleed or detach the retina (proliferative). Annual dilated eye exams are essential. Treatments include laser therapy and anti-VEGF injections to prevent vision loss.

Diabetic Nephropathy (Kidney Damage)

High blood sugar can damage kidney filtration units, leading to protein in the urine (microalbuminuria) and eventually kidney failure. Screening should include urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio. Early intervention with ACE inhibitors or ARBs can protect kidney function.

Diabetic Neuropathy (Nerve Damage)

Neuropathy affects peripheral and autonomic nerves. Peripheral neuropathy causes numbness, tingling, or pain commonly in the feet, leading to undetected injuries. Autonomic neuropathy may affect digestion, urination, or sexual function. Nurses should routinely assess for symptoms and educate patients on foot care and injury prevention.

Diabetic Foot Ulcers and Amputations

Foot problems result from a combination of neuropathy, poor circulation (PAD), and increased infection risk. Minor wounds may go unnoticed and worsen. If untreated, this can lead to severe infections or even amputation. Diabetes is a leading cause of non-traumatic lower limb amputations. Prevention includes daily foot inspection, proper footwear, prompt wound care, and regular foot exams by healthcare providers.

Macrovascular Complications

These involve large blood vessels and are essentially the accelerated development of atherosclerosis (plaque build-up in arteries) due to the metabolic effects of diabetes. People with diabetes often have coexisting hypertension and dyslipidemia, compounding cardiovascular risk. Major macrovascular issues include:

Cardiovascular Disease (CVD)

Diabetes dramatically increases the risk of heart attacks (MI) and angina. Many diabetics experience silent MIs due to neuropathy. Risk reduction involves controlling blood glucose, blood pressure, and cholesterol. The ADA considers diabetes itself a high-risk condition for cardiovascular events, and guidelines often recommend lipid-lowering therapy (like statins) for most diabetic patients over 40.

Atherosclerosis from diabetes can affect cerebral arteries, increasing the risk of ischemic strokes. Preventive strategies include controlling blood pressure, lipids, and avoiding smoking. Nurses should educate patients about the signs of stroke and its prevention.

Peripheral Arterial Disease (PAD)

Accelerated atherosclerosis in peripheral arteries (especially in the legs) causes PAD, which leads to claudication (pain on walking due to poor blood flow) and poor wound healing in the feet. PAD, combined with neuropathy, increases the risk of foot ulcers and amputations. Nurses should assess circulation (e.g., pulses) and promote vascular care.

Other Complications

- Heart Failure (Diabetic Cardiomyopathy). Related to poor glycemic control and heart damage over time.

- Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD). Common in those with insulin resistance or type 2 diabetes.

- Pregnancy Complications. Poorly controlled diabetes increases risks to both mother and baby, including congenital anomalies and preeclampsia.

Summary. Good glycemic control, blood pressure management, and lipid regulation help prevent or delay the development of complications. Preventive care (routine screenings, foot care, vaccinations) and patient education are equally vital in mitigating the impact of diabetes.

Management of Diabetes

The management of diabetes requires a multidisciplinary approach, combining medical treatment, lifestyle modification, blood glucose self-monitoring, and regular follow-up. The primary goals are to eliminate symptoms of hyperglycemia, achieve near-normal blood glucose levels, and prevent complications.

Nutrition (Dietary Management)

Based on the American Diabetes Association (ADA) 2024 Standards of Care, the following are the general lifestyle management guidelines for diabetes mellitus, with a focus on diet and physical activity.

- Individualized Meal Planning. Each person’s nutrition plan should reflect their cultural background, preferences, health conditions, and treatment goals. There is no single “diabetes diet.” Nurses should encourage collaboration with a registered dietitian for personalized meal guidance.

- Nutrient-Dense Food Choices. Promote whole, minimally processed foods like vegetables, fruits, whole grains, legumes, lean proteins, and healthy fats. These foods support stable blood sugar and reduce cardiovascular risk. Fiber-rich foods also enhance satiety and help manage cholesterol levels.

- Carbohydrate Management. Monitoring carbohydrate intake helps reduce blood glucose spikes. Carb counting and the glycemic index are beneficial for those on insulin or with type 1 diabetes.

- Moderate Alcohol Consumption. Alcohol can cause delayed hypoglycemia, especially in those taking insulin or sulfonylureas. If consumed, it should be with food and limited to 1 drink/day for women and 2 for men. Patients should be taught how alcohol interacts with their medications and blood sugar.

- Meal Timing and Consistency. Eating meals at regular intervals supports better glucose control, especially in patients on insulin or sulfonylureas. Skipping meals can lead to hypoglycemia. For patients on flexible insulin regimens, timing can be adjusted based on carb intake.

- Weight management. In type 2 diabetes, even a modest weight loss (5–10%) can significantly improve blood glucose control. Nurses should encourage lifestyle changes and refer overweight patients to diabetes education or weight management programs. For type 1 diabetes, the focus is on balancing insulin with a healthy diet to prevent weight gain or nutritional deficits.

- Heart-healthy and portion control. Recommend limiting saturated fats, trans fats, and excess salt, especially in patients with hypertension or kidney disease. Encourage lean proteins (chicken, fish, tofu) and moderate use of healthy fats like olive oil or avocado. Portion control is key to avoiding weight gain and controlling glucose.

- Avoid sugary drinks and excess sugar. Sugary beverages like soda, sweet tea, and juice cause rapid blood sugar spikes and offer little nutritional value. Encourage water, unsweetened drinks, or beverages with non-nutritive sweeteners like stevia or sucralose. Nurses should educate patients on hidden sugars in processed foods.

Nursing Tip. Nurses should reinforce nutrition advice provided by dietitians and assist patients in setting realistic dietary goals. In practice, encouraging patients to make incremental changes (like switching to water instead of soda, adding vegetables to each meal, and reducing portion sizes of high-carb foods) can be effective. Cultural food preferences must be respected and integrated into the meal plan for it to be sustainable.

Physical Activity

Regular exercise is a cornerstone for managing type 2 diabetes and is beneficial in type 1 as well (with some precautions). Exercise helps lower blood glucose by increasing insulin sensitivity and promoting glucose uptake by muscles. It also aids in weight management, improves cardiovascular health, and decreases the risk of diabetes-related complications.

- Adults with Diabetes (Type 1 or 2)

- Aim for at least 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity aerobic activity (e.g., brisk walking, swimming, cycling), spread across at least 3 days per week with no more than 2 consecutive days without activity.

- Add resistance training (e.g., lifting weights, bodyweight exercises) 2–3 times per week to improve muscle mass and glucose uptake.

- Children and Adolescents with Diabetes

- Encourage at least 60 minutes of physical activity daily, including aerobic and age-appropriate strength or bone-loading activities.

Exercise Safety Tips and Precautions for Diabetic Patients

1. Check Blood Glucose Before and After Exercise

Nurses should instruct patients to check their blood sugar before starting and after exercising. If it’s too low (<100 mg/dL), they may need a snack; if too high (>250–300 mg/dL) with ketones, exercise should be avoided to prevent worsening hyperglycemia or ketoacidosis.

2. Avoid Exercise During Peak Insulin Action.

Exercising when insulin is peaking (e.g., 1–2 hours after rapid-acting insulin) increases the risk of hypoglycemia. Patients should time physical activity when insulin levels are stable unless otherwise advised.

3. Stay Hydrated.

Encourage adequate fluid intake before, during, and after activity. Dehydration can impair glucose control and increase the risk of heat exhaustion or kidney stress, especially in those with existing complications.

4. Carry Fast-Acting Carbohydrates.

Remind patients to bring glucose tablets, fruit juice, or hard candy. These are beneficial in case of sudden hypoglycemia during physical activity.

5. Wear Proper Footwear and Inspect Feet

Advise the use of well-fitting, cushioned shoes with clean, dry socks. This reduces the risk of blisters, sores, and infections, which is significant for patients with peripheral neuropathy.

6. Start Slow and Progress Gradually

Encourage patients to begin with low-impact exercises like walking or swimming. Gradual progression helps the body adapt, reduces injury risk, and improves glucose control safely.

7. Avoid Exercise if Sick or Ketotic.

Advise against exercising when ill, dehydrated, or if ketones are present in the urine or blood. Physical activity under these conditions can worsen hyperglycemia or lead to diabetic ketoacidosis.

8. Inform a Friend or Exercise with a Partner.

Teach patients to inform someone before exercising or to work out with a partner. This ensures prompt help is available in case of hypoglycemia or sudden illness.

9. Be Aware of Post-Exercise Hypoglycemia.

Remind patients that blood sugar can drop several hours after exercise. Monitoring and a light snack may be needed to prevent delayed hypoglycemia.

10. Avoid Barefoot Walking or High-Impact Exercises

Walking barefoot or doing high-impact activities increases the risk of wounds and fractures, especially when sensation is impaired. Patients should always wear protective footwear during all activities.

Weight management

Weight loss is particularly beneficial for overweight or obese individuals with type 2 diabetes:

- A modest 5–7% weight loss can significantly improve insulin sensitivity, glycemic control, and cardiovascular health.

- Effective strategies include reducing calories, practicing portion control, and increasing physical activity.

- For patients with a BMI ≥35, bariatric surgery may be considered if lifestyle modifications alone are insufficient. This can lead to remission of type 2 diabetes in many cases.

Nursing Tip. Nurses should provide non-judgmental counseling, assess readiness to change, and refer patients to weight management programs or providers. Newer GLP-1 receptor agonists may also be considered as options for individuals requiring additional support.

Diabetes Self-Management Education (DSME)

Diabetes Self-Management Education (DSME) is a structured process that teaches individuals with diabetes how to manage their condition effectively on a day-to-day basis. It includes guidance on blood glucose monitoring, medication administration, dietary choices, physical activity, complication prevention, and coping strategies. The goal is to empower patients with the knowledge and skills needed to make informed decisions. This is usually provided by certified diabetes care and education specialists (often nurses or dietitians).

Self-Monitoring of Blood Glucose (SMBG)

SMBG involves using a glucometer to check capillary blood glucose, typically through a fingerstick. The frequency of testing depends on the patient’s treatment plan:

- Intensive Insulin Therapy (multiple daily injections or insulin pump).

- Testing is done before meals, at bedtime, and sometimes 2 hours after meals or overnight, totaling 4–6 times per day or more.

- This helps in adjusting insulin doses and avoiding hypoglycemia.

- Oral Medications with Low Hypoglycemia Risk (e.g., metformin).

- Testing is conducted less frequently, typically once daily at varying times or a few times per week, primarily to assess control trends.

- Stable Type 2 Diabetes (non-insulin dependent).

- Daily SMBG may not be necessary if A1C is on target, but occasional fasting and post-meal checks help assess the effects of food and activity.

- Sick Days or Therapy Adjustments.

- More frequent monitoring is recommended to catch fluctuations early.

Nursing Tip. Teach patients proper glucometer use, including hand hygiene before fingersticks and accurate logging of results. Explain individualized target ranges typically 80–130 mg/dL fasting and under 180 mg/dL post-meal for non-pregnant adults and provide clear guidance on actions to take for abnormal readings. Nurses should review recorded glucose data regularly to identify trends and recommend necessary behavioral or treatment adjustments to the physician.

Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM)

CGM is a technology that continuously tracks glucose levels in the interstitial fluid using a small sensor inserted just under the skin. Readings are updated every 5 to 15 minutes, providing dynamic insight into glucose trends. The ADA now recommends CGM for most patients with type 1 diabetes (and many with type 2 on intensive insulin) to improve glycemic control. CGM provides a more complete picture of glucose trends and time-in-range, helping to prevent hypoglycemia and guide insulin adjustments.

Types of CGM

- Real-time CGM (rtCGM). Displays live glucose data to the user in real time.

- Retrospective CGM (Professional CGM). Stores data that can be downloaded and reviewed later by healthcare providers.

Nursing Tip. Nurses teach patients (or caregivers) on proper use, sensor calibration, troubleshooting, and when to verify CGM readings with fingerstick testing.

Hemoglobin A1C (HbA1c)

Hemoglobin A1C (HbA1c) is a key indicator of long-term glycemic control, reflecting the average blood glucose levels over the past two to three months. It is a testing tool for monitoring diabetes management and evaluating the effectiveness of treatment plans. Testing is typically recommended every three months if there have been recent changes in therapy or if the patient’s blood glucose levels are not at target. For individuals with stable and well-controlled diabetes, testing may be done every six months.

- Target Range (General guideline)

- <7% for many non-pregnant adults.

- <6.5% for younger, healthier patients (if achievable without hypoglycemia).

- <7.5–8% for older adults or those with comorbidities.

Nursing Tip. When educating patients, emphasize that A1C reflects the average blood glucose over the past 2–3 months rather than daily highs and lows. Help patients understand how A1C relates to estimated glucose levels, for example, an A1C of 7% corresponds to approximately 154 mg/dL. Use A1C results to cross-check self-monitoring blood glucose (SMBG) logs, especially when values seem inconsistent, and guide adjustments in the care plan accordingly.

Pharmacologic Management

Insulin Therapy

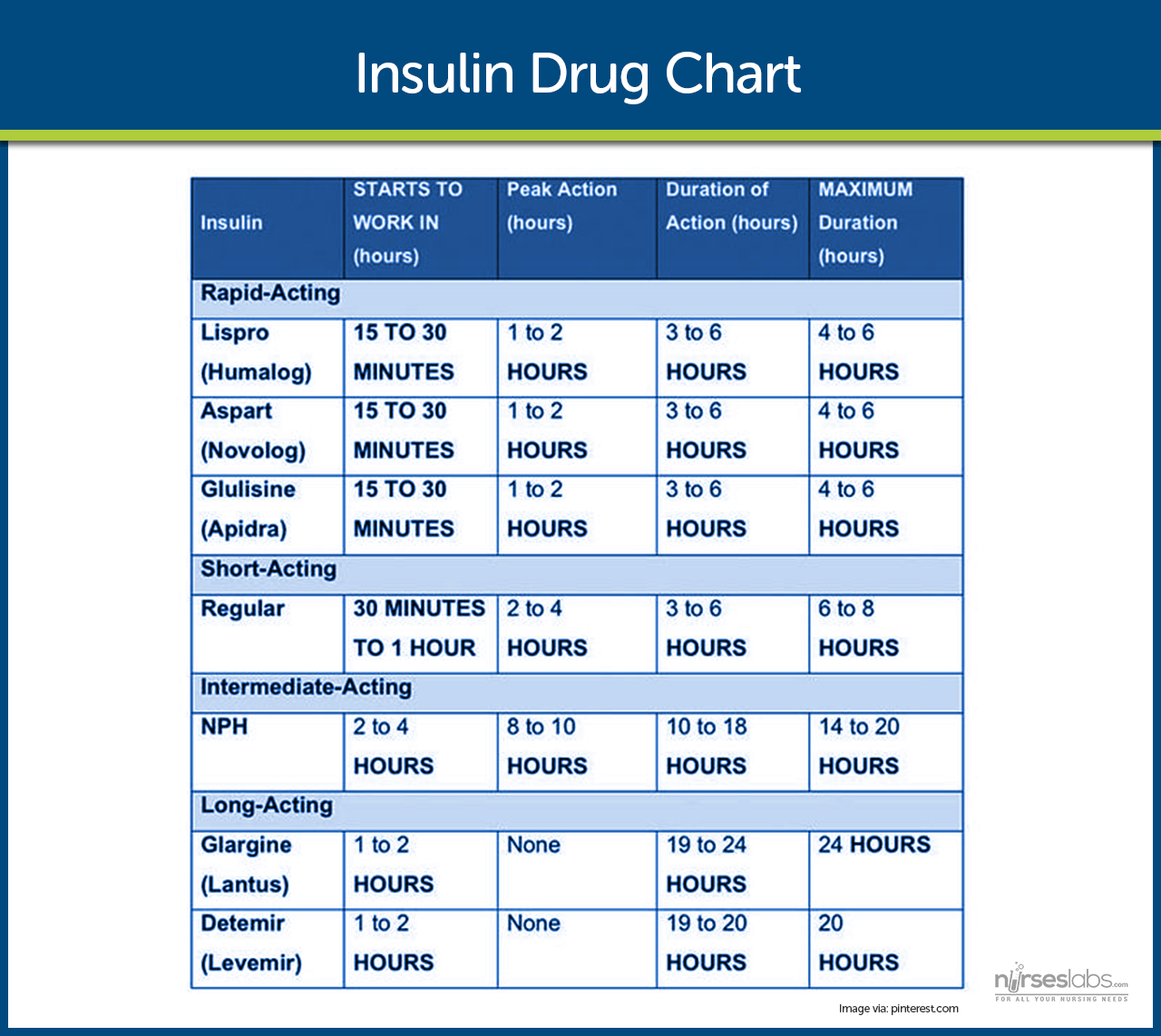

Insulin is required for survival in type 1 diabetes and is often eventually needed in type 2 as the disease progresses or during intercurrent stress (like hospitalization, surgery, or pregnancy). Modern insulin therapies are designed to mimic natural insulin patterns, featuring a basal insulin for around-the-clock coverage and bolus insulins for mealtime use. There are several types of insulin, classified by their speed of onset and duration of action:

- Rapid-acting insulin analogues, e.g., Insulin lispro (Humalog®), Insulin aspart (NovoLog®), Insulin glulisine (Apidra®). These begin working within 5 to 15 minutes after injection, peak at around 1 hour, and last for about 3 to 5 hours. They are typically injected immediately before meals and are commonly used in insulin pumps. These insulins reduce the risk of delayed hypoglycemia and provide flexibility in meal timing. In pediatrics, lispro and aspart are approved for children as young as 2 to 3 years old.

- Short-acting insulin, such as Regular insulin (Humulin R, Novolin R), has an onset of action within 30 to 60 minutes, peaks between 2 to 4 hours, and lasts 5 to 8 hours. It must be administered approximately 30 minutes before meals and is the only insulin that can be given intravenously, making it essential in emergencies like diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) or hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state (HHS). In pediatrics, regular insulin is an option, but it has largely been replaced by rapid-acting analogues for their ease of use.

- Intermediate-acting insulin, such as NPH insulin (Neutral Protamine Hagedorn, Humulin N, Novolin N), has a slower onset of 1 to 2 hours and a peak effect around 4 to 12 hours, with a duration of up to 24 hours. It is usually given twice a day for basal control. Due to its pronounced peak and variability, NPH carries a higher risk of mid-day or nocturnal hypoglycemia, especially if meals or snacks are missed. It remains common in type 2 diabetes regimens and in resource-limited settings.

- Long-acting (Basal) insulin analogues such as Insulin glargine (Lantus® U-100, Basaglar®; also Toujeo® glargine) and Insulin detemir (Levemir®), provide consistent insulin levels with minimal peaks. Glargine has a duration of up to 24 hours and is usually dosed once daily. Detemir may require twice-daily dosing in some patients. These basal insulins reduce the risk of hypoglycemia compared to NPH and are commonly used in both type 1 and type 2 diabetes. They are approved for pediatric use in children around age six (6) and above.

- Ultra-long-acting insulin, like Insulin degludec (Tresiba® U-100 or U-200) and U-300 glargine (Toujeo®), is a newer ultra-long option. Degludec has an onset of ~1 hour and lasts 42 hours or more, with a very flat profile. They provide very flat insulin levels, allowing for greater flexibility in injection timing. Degludec is approved for use in children as young as 1 year old and is ideal for patients with variable schedules or a history of nocturnal hypoglycemia.

- Pre-mixed insulins, such as 70/30 (NPH/regular) or 75/25 (NPL/lispro), combine intermediate-acting and rapid- or short-acting insulins in a fixed ratio. These are administered two to three times daily and cover both basal and prandial needs. While convenient for patients who struggle with complex regimens, pre-mixed insulins require consistent meal timing and are less flexible for dose adjustments. They are more commonly used in the treatment of type 2 diabetes.

Insulin Therapy Regimen in Diabetes Management

1. Basal-Bolus Regimen (Multiple Daily Injections – MDI)

This regimen uses long-acting insulin once or twice daily (basal) and rapid-acting insulin before meals (bolus). It mimics normal pancreatic function and allows flexibility in meal timing. Frequent blood glucose monitoring is essential to adjust doses accurately.

2. Continuous Subcutaneous Insulin Infusion (CSII) – Insulin Pump

An insulin pump delivers rapid-acting insulin continuously throughout the day (basal rate) with additional doses at meals (boluses). It offers better glucose control and fewer injections. Proper training and frequent glucose checks are needed for safety.

3. Split-Mixed Regimen (Less common)

Uses intermediate-acting insulin (e.g., NPH) mixed with short-acting insulin twice daily. Less flexible and not as physiologic, but may be used in settings with limited resources. Requires consistent meal timing to prevent hypoglycemia.

Insulin Regimens for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM)

1. Basal Insulin Only

Once-daily long-acting insulin (e.g., glargine, detemir) is added to oral meds to control fasting glucose. It is often the starting point for insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes. Simple and effective with low hypoglycemia risk.

2. Basal-Bolus Regimen

Combines long-acting insulin (basal) with rapid-acting insulin at meals (bolus), similar to T1DM regimens. Used when basal insulin alone no longer maintains glycemic control. Requires education, meal planning, and frequent glucose checks.

3. Premixed Insulin Regimen

Uses fixed combinations of intermediate- and short- or rapid-acting insulin (e.g., 70/30 insulin) given twice daily before breakfast and dinner. Convenient for patients with routine eating patterns. Less flexible and may cause hypoglycemia if meals are delayed.

Side effects of insulin

- Hypoglycemia (Low Blood Sugar). This is the most common side effect of insulin. It occurs when too much insulin is taken, meals are skipped or delayed, or physical activity increases without adjusting the dose. Symptoms include shakiness, sweating, confusion, and, in severe cases, loss of consciousness.

- Weight Gain. Insulin promotes fat storage and can lead to weight gain, especially when glucose control improves. Some patients may also eat more to prevent or treat low blood sugar, which can contribute to added weight.

- Lipodystrophy. Repeated injections at the same site can cause lipohypertrophy (the development of fat lumps) or lipoatrophy (the loss of fat). These changes can interfere with insulin absorption, leading to unpredictable glucose control.

- Allergic Reactions. Although rare with modern insulin, some patients may experience localized reactions, such as redness, swelling, or itching, at the injection site. Severe allergic responses are uncommon but possible.

- Edema (Fluid Retention). Initiating insulin therapy may cause mild swelling in the hands or feet due to fluid retention. This is usually temporary but should be monitored, especially in patients with heart or kidney conditions.

Non-Insulin Medications for Type 2

The non-insulin medications for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) are commonly called oral hypoglycemic agents (OHAs) and non-insulin injectable antidiabetic agents that address different aspects of the disease. Key categories include:

- Metformin. Metformin is the first-line oral drug for type 2 diabetes. It works by reducing liver glucose production and improving insulin sensitivity. It doesn’t cause hypoglycemia when used alone, but may cause gastrointestinal upset, especially when first started. It is avoided in patients with severe kidney disease due to the risk of lactic acidosis.

- Sulfonylureas (e.g., glipizide, glyburide, glimepiride). These medications increase insulin secretion from the pancreas. They lower blood sugar effectively but can cause hypoglycemia, especially if meals are skipped, and may cause weight gain. Nurses should educate patients about the timing of meals to avoid low blood sugar events.

- Thiazolidinediones (TZDs) (e.g., pioglitazone). TZDs enhance insulin sensitivity in muscle and fat tissue and do not cause hypoglycemia when used alone. However, they often cause weight gain and fluid retention, so they are not suitable for patients with heart failure. Pioglitazone may have added benefits for those with fatty liver disease.

- DPP-4 Inhibitors (e.g., sitagliptin, linagliptin). These drugs improve insulin release after meals and reduce glucagon levels by preserving incretin hormones. They are weight-neutral and have a low risk of hypoglycemia. Rarely, they may cause side effects such as pancreatitis or joint pain.

- SGLT2 Inhibitors (e.g., empagliflozin, canagliflozin, dapagliflozin). These drugs help remove excess glucose through the urine and offer added benefits like weight loss, lower blood pressure, and kidney and heart protection. Common side effects include urinary tract infections and genital yeast infections. Nurses should stress the importance of hydration and hygiene.

- GLP-1 Receptor Agonists (e.g., liraglutide, semaglutide, exenatide). These injectable drugs mimic natural hormones to increase insulin when needed, slow digestion, reduce appetite, and lower glucagon. They are very effective for lowering A1C and promoting weight loss. Nausea is common, especially at the start, and they are not recommended for patients with a history of certain thyroid tumors.

- Insulin (in Type 2 Diabetes). Insulin may be added if blood sugar remains uncontrolled with oral or injectable medications. Treatment often starts with long-acting (basal) insulin and may progress to more complex regimens. Insulin can cause weight gain and hypoglycemia, so careful dose adjustments and education are essential.

- Important: When type 2 patients are started on insulin, some oral medications may be continued (such as metformin or SGLT2/GLP-1), while others may be reduced or stopped (such as sulfonylureas) to avoid redundancy and hypoglycemia.

- Other medications

- Meglitinides (e.g., repaglinide). Short-acting insulin secretagogues are taken before meals; they are effective but can cause hypoglycemia if meals are missed.

- Alpha-glucosidase inhibitors (e.g., acarbose). Delay carbohydrate absorption in the gut; side effects include bloating and flatulence.

- Amylin analogs (e.g., pramlintide). Injectable agent used with insulin to slow gastric emptying and suppress appetite; may help with post-meal glucose control, but adds injection burden.

Guidelines for Selecting Type 2 Diabetes Medications

1. Consider Co-Morbid Conditions

- Heart Failure or Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD). → SGLT2 inhibitors (e.g., empagliflozin) are preferred due to proven benefits in reducing heart failure risk and slowing CKD progression.

- Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease (ASCVD) or Need for Weight Loss. → GLP-1 receptor agonists (e.g., semaglutide) are prioritized for their cardioprotective effects and significant weight reduction benefits.

2. Start with Metformin.

- Metformin is usually the first-line agent unless contraindicated (e.g., in advanced kidney disease).

- After assessing effectiveness and patient tolerance, a second agent is added based on individualized clinical needs and co-morbidities.

3. Use Combination Therapy When Needed.

- Most patients will eventually require two or three medications to achieve and maintain optimal blood glucose control.

- Combination therapy should be tailored to the patient’s lifestyle, comorbidities, risk of hypoglycemia, and cost considerations.

Summary: Difference between Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

| Category | Type 1 DM | Type 2 DM |

| Cause | Autoimmune destruction of pancreatic beta cells | Insulin resistance with progressive beta-cell dysfunction |

| Onset | Rapid, typically over days or weeks | Gradual, often over months or years |

| Commonly Affected | Children or young adults | Adults over 40; increasingly seen in adolescents |

| Initial Signs | Polyuria, polydipsia, polyphagia, weight loss, fatigue | Fatigue, recurrent infections, blurred vision, and slow wound healing |

| Insulin Production | Little to none (absolute insulin deficiency) | Initially normal or high, then gradually decreases |

| Treatment Requirement | Requires lifelong insulin therapy | High risk for Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA); may be the first presentation |

| DKA or HHS Risk | High risk for Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA); may be first presentation | Risk for Hyperglycemic Hyperosmolar Syndrome (HHS), especially in older adults with poorly controlled diabetes |

| DKA or HHS Symptoms | Abdominal pain, vomiting, fruity breath, Kussmaul respirations, dehydration, altered consciousness | Profound hyperglycemia (>600 mg/dL), dehydration, confusion, minimal ketones |

| Emergency Concern | About 1/3 of newly diagnosed children present with DKA; early recognition is critical. | HHS is a medical emergency with high mortality |

| Other Findings | May be delayed or prevented through a healthy lifestyle | Often, there are no physical signs before the onset |

| Prevention | Not preventable | May be delayed or prevented through healthy lifestyle |

Comprehensive Care and Follow-up

Effective diabetes management involves more than just controlling blood sugar levels. It also consists of managing blood pressure and cholesterol to reduce cardiovascular risk. Antihypertensive medications, particularly ACE inhibitors or ARBs, are commonly used, especially in patients with kidney involvement. Statins are often prescribed for cholesterol control, and low-dose aspirin may be considered for those with existing cardiovascular disease or high risk. Smoking cessation is also essential, as smoking significantly increases the risk of heart disease, stroke, and amputations.

Routine Screenings and Preventive Measures

Annual screenings help detect complications early. Patients should have yearly eye exams to monitor for diabetic retinopathy, annual foot exams (more frequently if high-risk), and kidney function tests, including urine albumin and eGFR, at least once a year. Vaccinations are also necessary; individuals with diabetes should receive an annual influenza vaccine, pneumococcal vaccines, and the hepatitis B vaccine if they are not already immune.

Psychosocial and Emotional Support

Living with diabetes is emotionally and mentally demanding. Nurses should routinely assess for barriers such as financial hardship, low health literacy, depression, or lack of social support. Referrals to social workers, diabetes educators, or peer support groups can help. Emotional support is key to encouraging long-term adherence and engagement in care.

Clinical Targets and Individualization

Standard targets include an A1C <7%, blood pressure <130/80 mmHg (or <140/90 for some), and LDL cholesterol <70 mg/dL in patients with cardiovascular disease. However, these goals must be personalized. For older adults with multiple comorbidities, a higher A1C (e.g., 7.5–8%) may be acceptable, while younger patients planning pregnancy may require tighter control (A1C <6.5%).

Sick Day Management

Patients should never stop insulin during illness, especially in type 1 diabetes. Illness often raises glucose levels even when food intake is reduced. Blood glucose should be checked every 4 hours, and ketones should be monitored if the glucose level exceeds 240 mg/dL. Hydration should be emphasized; sugar-free fluids are recommended for individuals with hyperglycemia, while carbohydrate-containing fluids are suggested for those with limited food intake. Patients should know when to seek medical care, such as persistent vomiting, high fever, or ketones not resolving with insulin. Nurses should provide a clear sick day plan and teach patients or caregivers how to follow it.

Hospitalization and Surgery

Hospital stays often require temporary adjustments to diabetes therapy, with insulin commonly used for tighter control. IV insulin infusions are frequently administered during critical illness or surgery. Nurses play a vital role in closely monitoring glucose levels, managing insulin drips, and guiding patients through a safe transition back to their home regimen with appropriate education.

Diabetes in Pregnancy

Pregnancy demands tight glucose control to reduce risks for the fetus. Insulin is the preferred treatment, though metformin or glyburide may be used in select cases. Nurses working in obstetrics should understand the increased insulin requirements during pregnancy and help coordinate glucose monitoring, dietary support, and fetal surveillance.

Special Considerations: Pediatric Diabetes

Managing diabetes in children and adolescents presents unique challenges and requires a family-centered approach. The majority of pediatric diabetic patients have Type 1 diabetes and are insulin-dependent, though type 2 is increasingly seen in youths due to rising obesity. Key points for pediatric diabetes care include:

Diagnosis and Early Recognition

Type 1 diabetes is the most common in children, but type 2 is increasingly seen due to rising childhood obesity. Young children may not exhibit classic symptoms, so nurses should recognize signs such as excessive thirst, frequent urination, and fatigue. Any suspicion should prompt immediate glucose and ketone testing.

Glucose Targets and Insulin Management

For most children, the A1C goal is <7.5%, though <7.0% may be ideal if safe. Glucose targets are generally higher in very young children to prevent hypoglycemia. Children often use basal-bolus insulin regimens, which are frequently supported by insulin pumps or continuous glucose monitors (CGMs), to improve safety and control. Nurses should be familiar with these technologies and educate families accordingly.

Nutrition, Growth, and Education

Meal plans must support normal growth while regulating glucose levels. Carbohydrate counting is taught early to allow flexible eating with insulin adjustments. Nurses should collaborate with dietitians and support insulin adjustments for physical activity. Schools must accommodate the needs of students with diabetes, and nurses help train teachers, school nurses, and caregivers.

Psychosocial Needs

Managing diabetes is challenging for children and families. Support should include education, emotional counseling, and connection to diabetes camps or peer groups. Nurses help transition care responsibilities as children grow and support adolescents struggling with adherence or emotional burden.

Preventing Complications and Transition to Adult Care

Screening for complications, such as eye or kidney disease, typically begins in puberty or after a few years of diagnosis. For type 2 youth, screening starts at diagnosis. As teens transition to adulthood, nurses support them in navigating changes in lifestyle, care teams, and self-management responsibilities.

Summary. Pediatric diabetes management requires striking a balance between stringent control and safety (avoiding hypoglycemia), considering the child’s cognitive development in educational strategies, and providing comprehensive support to the child and their family. Achieving reasonable control in youth can prevent the early onset of complications and set the stage for healthier adulthood.

Special Considerations: Diabetes in Older Adults

Diabetes is prevalent in older adults – nearly 1 in 3 Americans over 65 has diabetes. Managing diabetes in the elderly requires special attention to comorbidities, functional status, and the higher risks they face. Key considerations include:

Individualized Targets and Hypoglycemia Risk

Older adults with good functional status may aim for A1C goals around 7.0–7.5%. For frail patients or those with multiple comorbidities, higher targets (e.g., <8–8.5%) are safer. Hypoglycemia is especially dangerous in this population due to fall risk, cognitive decline, and cardiovascular effects. Nurses should simplify regimens and avoid agents with high hypoglycemia risk.

Functional and Cognitive Assessments

Older adults vary widely; some can manage complex regimens, while others require support due to vision, dexterity, or cognitive decline. Nurses should assess abilities and adjust care accordingly. Tools and caregiver support may be necessary for tasks such as glucose monitoring or insulin injection.

Medication Safety and Simplification

Some drugs (e.g., glyburide) are avoided in the elderly due to the prolonged hypoglycemia risk. Metformin remains first-line but should be reviewed as kidney function declines. Thiazolidinediones may worsen heart failure. SGLT2 inhibitors offer cardiovascular benefits but require monitoring for dehydration and infections. Nurses play a significant role in promoting medication safety and help simplify regimens to support better adherence.

Addressing Comorbidities and Complications

Hypertension, dyslipidemia, and existing complications like neuropathy are common. Blood pressure and cholesterol targets should be met cautiously. Nurses should routinely assess patients for foot problems, fall risk, and vision changes. Foot exams and eye screenings remain critical, and home safety assessments may also be necessary.

Nutrition and Social Factors

Older adults may experience malnutrition, reduced appetite, or financial challenges. Nurses assess for obstacles to meal preparation and medication access, coordinating with social services when appropriate. Nutritional plans should support adequate protein and calorie intake while reducing the risk of hypoglycemia.

End-of-Life Care and De-intensification

In patients with limited life expectancy or serious illness, the goal of diabetes care shifts to comfort. Tight control is no longer prioritized—focus should be on avoiding symptomatic highs and preventing hypoglycemia. Nurses in long-term care settings advocate for simplified regimens and help families align care with the patient’s goals and quality of life.

Summary. Diabetes care in older adults should be individualized and cautious. The mantra is “avoid hypoglycemia, avoid overly aggressive treatment, but control enough to minimize acute problems.” Quality of life considerations are paramount; complicated regimens that cause anxiety or confusion may do more harm than good. Nurses can help find that balance and provide a care plan that aligns with the patient’s health status and wishes.

Nursing Management and Care Plans

Nurses are at the forefront of caring for patients with diabetes, providing education, monitoring for complications, and intervening to maintain optimal health. Nursing management spans from hospital acute care (e.g., managing insulin drips in DKA) to outpatient settings (teaching self-care, adjusting regimens with the team). Below are key nursing considerations, assessments, diagnoses, interventions, and evaluation metrics for patients with diabetes mellitus.

Nursing Assessment

A thorough assessment establishes the baseline and identifies problems requiring attention:

- Chief complaints and classic symptoms. Ask about excessive thirst (polydipsia), frequent urination (polyuria), excessive hunger (polyphagia), fatigue, unexplained weight changes, blurred vision, recurrent infections, or delayed wound healing.

- Health History.

- Family History. Inquire about any first-degree relatives with diabetes, as this may indicate a genetic predisposition.

- Medication Review. Ask about current and past use of medications that may affect glucose levels, particularly corticosteroids, antipsychotics, or specific immunosuppressants.

- Lifestyle Factors. Assess dietary habits, physical activity level, alcohol intake, smoking status, and any recent weight changes.

- Pediatric focus. In children, gather information from parents or caregivers about appetite, behavior, growth patterns, and symptoms, such as bedwetting.

- Geriatric focus. For elderly patients, assess cognitive function, physical ability to self-manage, vision, dexterity, and the presence of social support at home.

- If the patient has a known diagnosis of diabetes.

- Identify the type of diabetes and date of diagnosis.

- Review prescribed medications, including names, dosages, frequency, and adherence.

- Ask about home blood glucose monitoring practices—how often they check, typical readings, and if a log is maintained.

- Document the most recent HbA1c result, if available.

- Explore the history of hypoglycemia episodes, frequency, severity, and known triggers or causes.

- Identify potential issues such as financial limitations, difficulty accessing supplies, fear of injections, or lack of family or caregiver support.

- Physical Examination

- Vital signs.

- Blood Pressure. Check for hypertension (goal <130/80 mmHg for most)

- Heart Rate and Respiratory Rate. Elevated in dehydration, infection, or DKA

- Temperature. Monitor for possible infections.

- Weight/BMI. Baseline for nutritional status, obesity, or unintended weight loss

- Hydration status.

- Dry mucous membranes, poor skin turgor, and sunken eyes may indicate dehydration associated with hyperglycemia or diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA).

- Skin.

- Inspect the skin for signs of dryness, bruising, fungal infections, or slow-healing wounds (all common in poorly controlled diabetes).

- Examine insulin injection or pump sites for redness, swelling, infection, or lipodystrophy. C

- Check the neck and axilla for acanthosis nigricans, a darkened, velvety skin patch that suggests insulin resistance.

- Eyes.

- Ask about any visual disturbances, such as blurred vision or floaters.

- If trained, use an ophthalmoscope to check for signs of diabetic retinopathy, including microaneurysms, retinal hemorrhages, or cotton wool spots.

- Oral cavity.

- Cardiovascular.

- Palpate peripheral pulses, especially the dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial arteries, to assess circulation to the lower limbs.

- Auscultate the carotid arteries for bruits

- Check for signs of peripheral vascular disease, including cold extremities, delayed capillary refill, or changes in skin color.

- Neurologic.