Spina Bifida, a congenital neural tube defect, presents a range of complex challenges that require expert care and attention. It is a condition that affects the spine and spinal cord during early fetal development, leading to various physical and neurodevelopmental impairments. In this article, the focus is on exploring the multifaceted aspects of Spina Bifida and the critical role that nursing professionals play in providing comprehensive care and support to individuals and families facing this condition.

What is Spina Bifida?

- Spina bifida is part of a group of birth defects called neural tube defects.

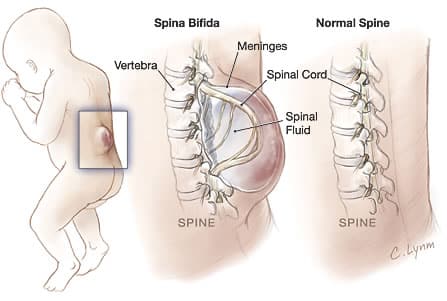

- Caused by a defect in the neural arch generally in the lumbosacral region, spina bifida is a failure of the posterior laminae of the vertebrae to close; this leaves an opening through which the spinal meninges and spinal cord may protrude.

Classification

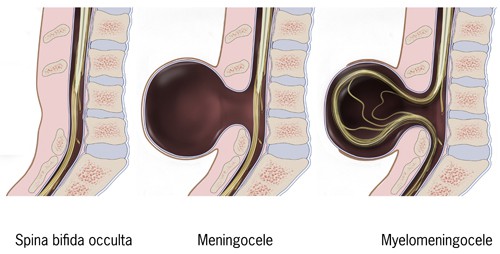

Spina bifida can be classified into three:

- Spina bifida occulta. A bony defect that occurs without soft tissue involvement is called spina bifida occulta.

- Spina bifida with meningocele. When part of the spinal meninges protrudes through the bony defect and forms a cystic sac, the condition is termed spina bifida with meningocele.

- Spina bifida with myelomeningocele. In spina bifida with myelomeningocele, there is a protrusion of the spinal cord and the meninges, with nerve roots embedded in the wall of the cyst.

Pathophysiology

Neural tube defects are the result of a teratogenic process that causes failed closure and abnormal differentiation of the embryonic neural tube.

- During prenatal development, neuroectoderm thickens into the neural plate which folds into a neural groove by the time somites appear.

- The groove deepens to become the neural tube, and dorsal fusion begins centrally, extending cephalad and caudally, with the cephalad pole fusing at the 25th day.

- The ventricle becomes permeable at the 6th to 8th week of gestation but this does not proceed normally in patients with spina bifida.

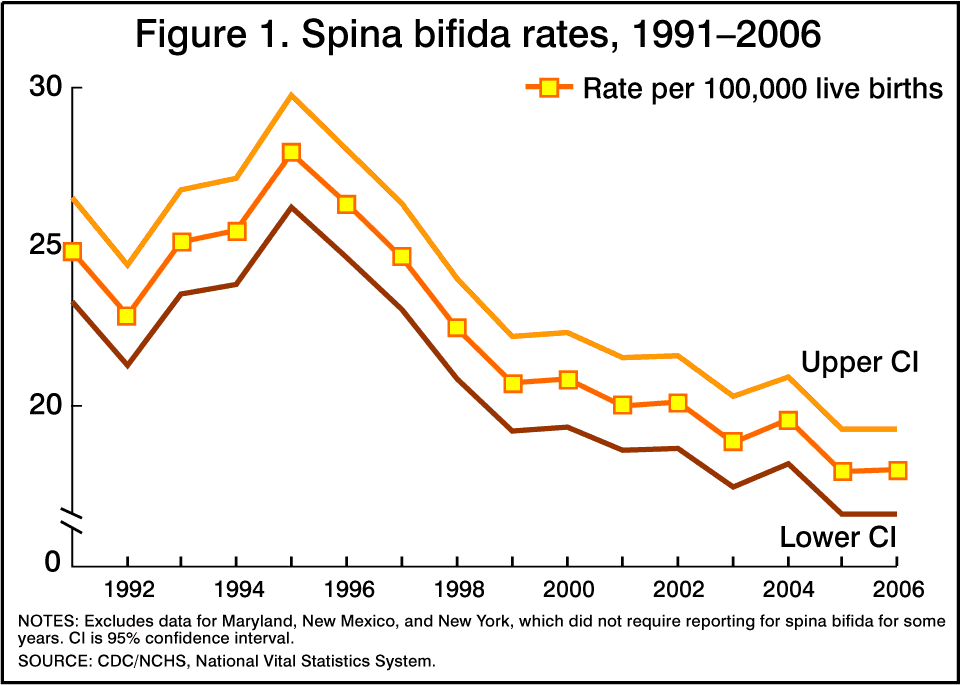

Statistics and Incidences

The occurrence of spina bifida in the United States and internationally are estimated in the following:

- The incidence of spina bifida has been estimated at 1-2 cases per 1000 population, with certain populations having a significantly greater incidence based on genetic predilection.

- Neural tube defects are the second most common type of birth defect after congenital heart defects, and myelomeningocele is the most common form of neural tube defect.

- In the United States, approximately 1, 500 infants are born with myelomeningocele each year.

- Birth incidence of the disease was reported to be 4.4-4.6 cases per 10 000 live births from 1983-1990.

- Rates varied by region, with the incidence being higher on the East Coast than on the West Coast and the highest rates occurring in Appalachia.

- The rate of myelomeningocele and other neural tube defects has declined since the late 20th century.

- The average worldwide incidence of spina bifida is 1 case per 1000 births, but marked geographic variations occur.

- Neural tube defects occur at frequencies (per 10, 000 births) ranging from 0.9 in Canada and 0.7 in central France to 7.7 in the United Arab Emirates and 11.7 in South America.

- The highest rates of spina bifida are found in parts of the British Isles, mainly Ireland and Wales, where 3-4 cases of myelomeningocele per 1000 population have been reported.

- The reported overall incidence of myelomeningocele in the British Isles is 2-3.5 cases per 1000 live births.

- In France, Norway, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, and Japan, a low prevalence is reported, being just 0.1-0.6 cases per 1000 live births.

- According to the CDC, the prevalence of spina bifida in the United States is higher in the white and Hispanic populations (2 and 1.96, respectively, per 10, 000 live births) than in the black population (1.74 per 10, 000 live births).

- Data from state and national surveillance systems from 1983-1990 found the birth prevalence rate of myelomeningocele to be slightly higher in females than in males (1.2:1).

Causes

The etiology in most cases of spina bifida is multifactorial, involving genetic, racial, and environmental factors, in which nutrition, particularly folic acid intake, is key.

- Low folic acid intake. Research indicates folate can reduce the incidence of neural tube defects by about 70% and can also decrease the severity of these defects when they occur.

- Genetics. If a woman gives birth to a baby with spina bifida, she has a higher-than-normal risk of having another baby with spina bifida too (about 5% risk).

- Certain medications. Some medications, such as some for treating epilepsy or bipolar disorder have been associated with a higher risk of giving birth to babies with congenital defects, such as spina bifida.

- Diabetes. Women with diabetes are more likely to have a baby with spina bifida, compared to other females.

- Obesity. Obese women, those whose BMI (body mass index) is 30 or more have a higher risk of having a baby with spina bifida. The higher the woman’s BMI is over 30, the higher the risk.

Clinical Manifestations

Clinical manifestations may vary depending on the type of spina bifida.

- Paralysis. If the opening occurs at the top of the spine, the patient’s legs are more likely to be completely paralyzed, and there will be other problems with movement elsewhere in the body.

- Cognitive symptoms. Problems occurring in the neural tube have a negative effect on brain development; the main part of the brain (cortex), especially the frontal part does not develop properly, leading to some cognitive problems.

- Arnold-Chiari malformation. There may also be Type 2 Arnold-Chiari malformation, an abnormal brain development involving the cerebellum – this may affect the patient’s language processing and physical coordination skills.

- Birthmark. There may be a small birthmark, dimple or tuft of hair on the skin where the spinal defect is.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

Assessment and laboratory findings of a patient with spina bifida may reveal the following:

- AFP levels. Elevated maternal alpha fetoprotein levels in the maternal seruma nd the amniotic fluid indicates the probability of CNS abnormalities.

- Ultrasonography. Ultrasonographic examination of the fetus may show an incomplete neural tube.

- Clinical examination. Diagnosis of spina bifida is made from clinical observation and examination.

- Other imaging studies. Additional evaluation of the defect may include magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT), and myelography.

Surgical Management

Many specialists are involved in the treatment of these newborns, especially in the case of myelomeningocele.

- Surgery. Surgery is required to close the open defect but may not be performed immediately, depending on the surgeon’s decision.

- Prenatal surgery. In this procedure — which takes place before the 26th week of pregnancy — surgeons expose a pregnant mother’s uterus surgically, open the uterus and repair the baby’s spinal cord.

- Ongoing care. Babies with myelomeningocele may also start exercises that will prepare their legs for walking with braces or crutches when they’re older.

- Cesarean birth. Cesarean birth may be part of the treatment for spina bifida; many babies with myelomeningocele tend to be in a feet-first (breech) position.

Nursing Management

Highly skilled nursing care is necessary in all aspects of the newborn‘s care.

Nursing Assessment

A routine newborn examination is conducted with emphasis on neurologic impairment.

- Physical examination. When collecting date during the examination, observe the movement and response to stimuli of the lower extremities; carefully measure the head circumference and examine the fontanelles.

- Assessment of knowledge regarding the defect. Determine the family’s knowledge and understanding of the defect, as well as their attitude concerning the birth of a newborn with such serious problems.

Nursing Diagnoses

Based on the assessment data, the major nursing diagnoses are:

- Risk for infection related to vulnerability of the myelomeningocele sac.

- Risk for impaired skin integrity related to exposure to urine and feces.

- Risk for injury related to neuromuscular impairment.

- Compromised family coping related to perceived loss of the perfect newborn.

- Deficient knowledge of the family caregivers related to the complexities of caring for a newborn with serious neurologic and musculoskeletal defects.

Nursing Care Planning and Goals

The major goals for the patient are to:

- Prevent infection.

- Maintain skin integrity.

- Prevent trauma related to disuse.

- Increase family coping skills, education about the condition, and support.

Nursing Interventions

News that the newborn child has a condition such as spina bifida can naturally cause the family to feel grief, anger, frustration, fear and sadness, however, nurses are there to help the family cope and understand the defect the child has.

- Prevent infection. Monitor the newborn’s vital signs, neurologic signs, and behavior frequently; administer prophylactic antibiotic as ordered; carry out routine aseptic technique; cover the sac with a sterile dressing moistened in a warm sterile solution and change it every 2 hours; the dressings may be covered with a plastic protective covering.

- Promote skin integrity. Placing a protective barrier between the anus and the sac may prevent contamination with fecal material, and diapering is not advisable with a low defect.

- Prevent contractures of lower extremities. Newborns with spina bifida often have talipes equinovarus (clubfoot) and congenital hip dysplasia (dislocation of the hips); if there is loss of motion in the lower limbs because of the defect conduct range-of-motion exercises to prevent contractures; position the newborn so that the hips are abducted and the feet are in a neutral position; massage the knees and other bony prominences with lotion regularly, then pad them, and protect them from irritation.

- Proper positioning of the newborn. Maintain the newborn in a prone position so that no pressure is placed on the sac; after surgery, continue this positioning until the surgical site is well healed.

- Promote family coping. Be especially sensitive to their needs and emotions; encourage family members to express their feelings and emotions as openly as possible; provide privacy as needed for the family to mourn together over their loss; encourage the family members to cuddle and touch the newborn using proper precautions for the safety of the defect.

- Provide family teaching. Give family members information about the defect and encourage them to discuss their concerns and ask questions; provide information about the newborn’s present state, the proposed surgery, and follow-up care; information shall be provided in small segments to facilitate comprehension; after the surgery, teach the family to hold the newborn’s head, neck, and chest slightly raised in one hand during feeding; also teach them that stroking the newborn’s cheeks helps stimulate sucking.

Evaluation

Expected outcomes from the patient include:

- Prevented infection.

- Maintained skin integrity.

- Prevented trauma related to disuse.

- Increased family coping skills, education about the condition, and support.

Documentation Guidelines

Documentation for a patient with spina bifida may include:

- Individual risk factors including recent or current antibiotic therapy.

- Signs and symptoms of infectious process.

- Characteristic of lesion or condition.

- Causative and contributing factors.

- Client’s/caregiver‘s understanding of individual risks and safety concerns.

- Current and past coping behaviors, emotional response to situation and stressors, support systems available.

- Plan of care.

- Teaching plan.

- Responses to interventions, teaching, and actions performed.

- Attainment or progress towards desired outcomes.

- Modifications to plan of care.

- Discharge needs, referrals made, and who is responsible for actions to be taken.

Leave a Comment